Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (September 29)

If you thought you knew everything about Ole Miss football–you probably didn’t.

If you thought you knew everything about Ole Miss football–you probably didn’t.

If you want to know everything about Ole Miss football, though, there’s a new resource that pretty much covers it all.

From the colorful to the unbelievable, the anguish to the exhilaration, Neil White’s new release Stories From 125 Years of Ole Miss Football (Nautilus) is filled with stories you’ve probably never heard and photos you’ve probably never seen.

“To build this book,” White states in the opening pages, “our team of writers and editors interviewed more than 60 players, coaches, journalists, widows, children, and fans. “Each interview started with the same request: ‘Tell us a story that most people don’t know.’”

The result is the ultimate football lovers’ dream: not just “new” stories, but an Appendix that includes charts and graphics highlighting many “Top 10” lists, best and worst games, coaches and seasons, team lineups and more.

Contributors to the book included Rick Cleveland, Billy Watkins, Robert Khayat, Jeff Roberson, and more.

An Oxford native and current resident, White has been a newspaper editor, magazine publisher, advertising executive and federal prisoner, and may best be known for his debut book, In the Sanctuary of Outcasts. Today he operates The Nautilus Publishing Co., writes plays and essays, and teaches memoir writing.

For context, please briefly share your own Ole Miss experience. It’s obvious in your book that you are a big Rebels fan!

Neil White

I’m a third generation Ole Miss guy. I attended my first football game at age 1. I was 8 years old when Archie-mania swept the South. I attended summer football camps and got to know Warner Alford and Junie Hovious and Eddie Crawford, as well as former players. We’re not a hunting or fishing family, so Ole Miss football games were what we did together. My father took me to games; I took my son to games. We still have tickets together.

As Stories from 125 Years of Ole Miss Football marks a milestone year of Rebel football, it is unique in that the entire book is filled with stories that required one main criteria: “Tell us a story that most people don’t know.” The result is a volume filled with secrets and little-known facts that, for most readers, will be brand new information! Tell me briefly about how you assembled the team of storytellers and editors that put this book together, and how they made it work.

As we interviewed the obvious contributors – Robert Khayat, Archie Manning, Jake Gibbs, Jesse Mitchell, Deuce McAllister and Perian Conerly–they would say, “You need to talk to . . . Dan Jordan, or Skipper Jernigan, or Billy Ray Adams.” So, the early interviewees knew who had the great untold stories. Picking the editors was much easier. Rick Cleveland, Billy Watkins, Chuck Rounsaville, Jeff Roberson, Don Whitten, and Langston Rogers could each write stories to fill five volumes.

The book took about a year to complete.

In the book, you explain the breadth of research it took to find and verify these stories. Tell me about that process.

I spent about seven months researching in the archives at Ole Miss, reading all the books that had ever been written about Ole Miss football, and researching hundreds of old newspaper reports. Then, we spent about five months interviewing individuals. Memory is subjective, at best. Sometimes we had conflicting stories. As we dug deeper, we almost always found some way to corroborate the story–or disprove it.

For example, most people assume – because it has been mis-reported for 67 years – that Bud Slay caught the lone touchdown pass in the 1952 Maryland upset. That game put Ole Miss on the national football map; Maryland had a 21-game win streak and the number one defense in the nation. Ray “Buck” Howell actually caught the pass from All-American Jimmy Lear, but the day after the game an AP report listed the name as “Bud Howell”–a combination of the two receivers. As it turns out, Ray “Buck” Howell is alive and well and living in Jackson. He’s such a humble, nice man. He says, “Now, I don’t want this to be about me”–then he pauses and smiles–“but I did catch the pass.” So, after 67 years, we get to set the record straight and give Howell the credit he deserves.

How did you choose the players and coaches whose stories you included in this book?

We included the stories from the players and coaches and their families who were the most forthcoming, and those whose stories were the most interesting, colorful, and impactful.

The early history of Ole Miss football is fascinating when compared to today’s game . . . as in, team members in the 1890s would grow their hair longer for protection, since players did not wear helmets! Who would you say should read this historical document for true fans?

Anyone who enjoys football or history or good stories. I especially like the stories that illustrate how crisis and fate lead to something, ultimately, wonderful for Ole Miss. For example, in 1943, Ole Miss didn’t have a football team. Coach Harry Mehre was charged with preparing students for war. He hired a young coach from Moss Point to train the cadets in hand-to-hand combat. That man’s name was Edward Khayat. He moved his family, including his five-year-old son Robert, to Oxford. They lived in faculty house #1. It was the first time the Khayats, who had been a Millsaps family, were affiliated with Ole Miss. That odd year, without a football team, changed the course of history for the university.

Is it your hope that, at some point years from now, someone else will pick up the tradition and continue the story?

Absolutely. If someone can use this book as a foundation for a 150-year project, wonderful. I read every book previously published on Ole Miss football. They were invaluable. I hope this one will be a part of that growing history.

Signed copies of Stories from 125 Years of Ole Miss Football are available at Lemuria and at our online store.

Brittney Morris’s hot debut novel presents a relevant and hard-hitting YA tale of a black teen game developer–17-year-old Kiera Johnson–who created the secret multiplayer role-playing game called Slay.

Brittney Morris’s hot debut novel presents a relevant and hard-hitting YA tale of a black teen game developer–17-year-old Kiera Johnson–who created the secret multiplayer role-playing game called Slay.

A self-acknowledged “steady diet of horror fiction and monster movies” as he was growing up has, for Arlinton, Texas, native Shaun Hamill, resulted in a debut novel that makes Halloween look like a day in the park.

A self-acknowledged “steady diet of horror fiction and monster movies” as he was growing up has, for Arlinton, Texas, native Shaun Hamill, resulted in a debut novel that makes Halloween look like a day in the park.

Téa Obreht’s sophomore novel

Téa Obreht’s sophomore novel

In her debut book

In her debut book

She soon realized that the stories she lived out as she discovered the thrill of the game, literally on the sidelines, were the stuff that would make a good read, and

She soon realized that the stories she lived out as she discovered the thrill of the game, literally on the sidelines, were the stuff that would make a good read, and

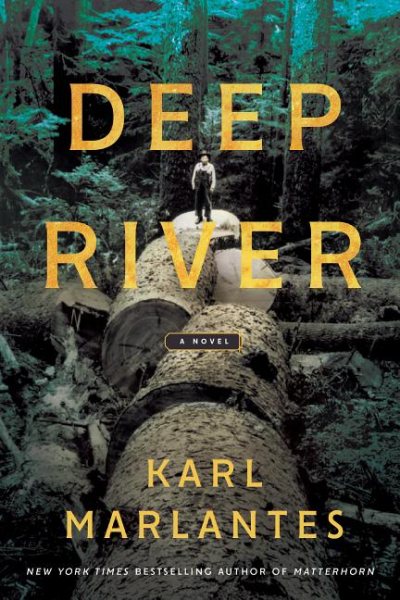

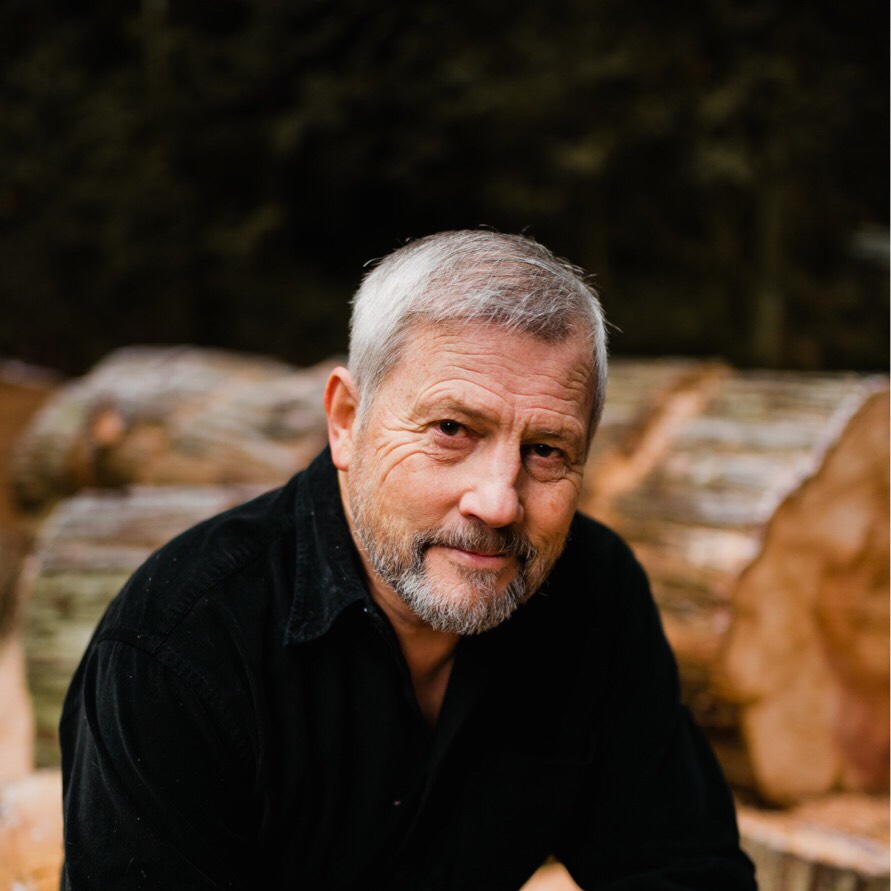

Karl Marlantes says his penchant for writing long novels comes naturally: he has much to tell through his stories and the undercurrents he masterfully weaves just below the surface.

Karl Marlantes says his penchant for writing long novels comes naturally: he has much to tell through his stories and the undercurrents he masterfully weaves just below the surface.

Oxford’s Lisa Howorth combines a humorous twist with the looming realities of an America on the cusp of the 1960s in her sophomore novel,

Oxford’s Lisa Howorth combines a humorous twist with the looming realities of an America on the cusp of the 1960s in her sophomore novel,

Growing up in a tight-knit Italian family living in Connecticut, Grames loosely borrows from some of her own experiences as she shares the tale of the indomitable Stella Fortuna, who gave birth to 11 children even as she lived through at least seven–maybe eight–near-death experiences.

Growing up in a tight-knit Italian family living in Connecticut, Grames loosely borrows from some of her own experiences as she shares the tale of the indomitable Stella Fortuna, who gave birth to 11 children even as she lived through at least seven–maybe eight–near-death experiences.

Multi-award-winning crime writer Rozan, herself a native and current resident of New York City, was intrigued when she first heard about the Delta’s long-established Chinese community, and proved that this “Most Southern Place on Earth” was also the best setting yet for another whodunit. And this time, it‘s personal: Lydia’s cousin–whom she never knew existed–has been accused of murdering his father.

Multi-award-winning crime writer Rozan, herself a native and current resident of New York City, was intrigued when she first heard about the Delta’s long-established Chinese community, and proved that this “Most Southern Place on Earth” was also the best setting yet for another whodunit. And this time, it‘s personal: Lydia’s cousin–whom she never knew existed–has been accused of murdering his father.