Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (October 28)

Award-winning New York-based photographer Rachel Cobb has spent years–decades, actually-chasing the wind.

And although such a pursuit would generally be considered fruitless for the rest of us, Cobb has defied conventional wisdom–she has captured the wind. What she has found, through the lens of her camera, is that this invisible force of nature is, at times, playful. Awe-inspiring. Destructive. Refreshing. Frightening. And utterly beautiful.

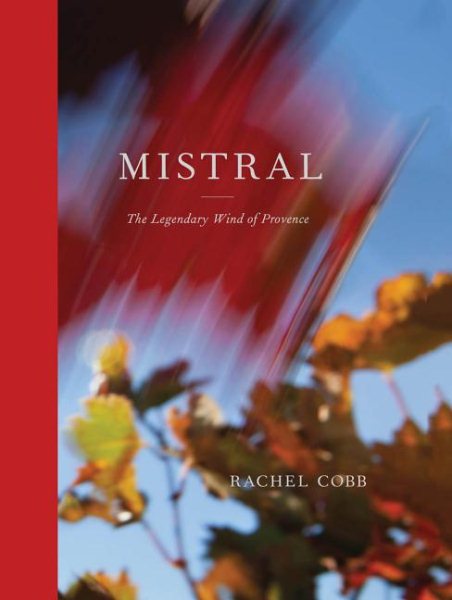

Cobb’s new book, Mistral: The Legendary Wind of Provence, is a photographic story of the relentless mistral, or strong wind, that evidence shows has likely blown through Provence, France, since before recorded time. Its impact on the area’s culture, architecture, agriculture, and social norms is revealed through stunning images of everyday life in the area.

Cobb’s new book, Mistral: The Legendary Wind of Provence, is a photographic story of the relentless mistral, or strong wind, that evidence shows has likely blown through Provence, France, since before recorded time. Its impact on the area’s culture, architecture, agriculture, and social norms is revealed through stunning images of everyday life in the area.

What she discovered is that this phenomenon is clearly visible in the form of “a leaf caught in flight, a bride tangled in her veil, spider webs oriented to withstand the gusts,” to new a few revealing signs. Accompanying these visuals are excerpts from writings by Paul Auster, Lawrence Durrell, Jean Giono, Frédéric Mistral, Robert Louis Stevenson, and others, who attempt to make sense of the power of the mistral.

Rachel Cobb

Cobb has photographed current affairs, social issues, and features in the U.S. and abroad for more than two decades. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Sports Illustrated, Time, Rolling Stone, Natural History, Stern, and Paris Match, among others. She has been recognized with Picture of the Year awards for her work during the 9/11 attacks in New York City and in war-torn Sarajevo; and a Marty Forscher Grant for Humanistic Photography.

Born and raised in Dallas, Cobb has lived in New York City since she graduated from Denison University in Ohio.

Please define mistral, and tell me what your book is about. How long did it take you to capture all of these images, start to finish?

The mistral is a cold, dry wind that blows down the Rhône River Valley through Provence and empties into the Mediterranean. It can blow 200 days a year. It is fierce–relentless, even. It can turn a summer day into a chilly affair. My book is an attempt to capture the feeling of wind, to make my audience experience this invisible force of nature and to show what it means to live in a place where wind is so often present.

The first photograph I made for this series was in 1998 on medium format transparency film using a 1959 Rolleiflex twin lens camera. I’d first imagined this series as a square-format, moody, black-and-white story of people enduring the wind, maybe inside while the wind beat against their houses.

Obviously, that idea had to go. Who would have understood it? Besides, color is essential to seeing the mistral. It clears the sky and turn sit brilliant blue. And red–locals say a red sky at night indicates a mistral will follow. My first image was of a vibrant red sky at night, and if you look carefully, you can see the trees already beginning to stir. The last image was made in September 2017. But is any photographer ever really finished with a project like this? It’s now such a part of me to look for and respond to wind, I can’t help but take photos.

Tell me how you came to know about the mistral that you have written about and photographed in this book. What was it about this wind phenomenon that heightened your interest so intently?

I’d been going to this region of France since I was a teenager. Anybody who spends any amount of time in Provence is well acquainted with its most famous wind. You simply can’t escape it. And people talk about it endlessly. They predict, they complain, they repeat old adages about how long it will last, how strong it will be.

It occurred to me that the mistral is an essential part of Provençal life, and in fact, it defines many aspects of life there. The plants and trees bend to the wind. Farmers both try to control it by planting rows of trees tightly together to protect their crops, and they also make use of it, for example, when they tie plastic strips to their cherry trees. The plastic flaps in the wind and scares away birds. Houses and other buildings are built with the wind in mind, not the sun. Entrances are always on the southern, sheltered side. On the windward side, there are few or no windows. Even spiders build their webs to reduce the brunt of the wind. The mistral is the story of this place.

How hard does the mistral in Provence generally blow?

I used to carry an anemometer while I was working so that I could record exactly how hard the wind was blowing. The Beaufort Scale of Wind Force breaks down wind speed into a scale of 1 to 12, and it describes wind’s effects on sea and on land. During a strong mistral, gusts can reach 12 on the scale–that’s greater than 73 miles per hour–which is the start of hurricane strength. A more common sustained mistral might blow at 35-50 miles per hour.

Which photos did you find most challenging to capture?

I have a background in newspaper photography, which was wonderful training for working quickly, but this project really challenged me. I had to be there when the wind blew, and I also had to find ways of showing wind’s effect on things without repeating myself too much. It took longer than any story I’ve ever done. It took me 10 years to get the images of the wind-blown snow atop Mont Ventoux. Conditions have to be just right. There’s a snowfall on the mountain, then slightly warmer weather softens the snow, then wind blows and freezes the snow as it’s blowing.

I would follow the weather in Provence from New York, and when I would see there was a mistral, I would call people who worked on the mountain to see if the conditions were right, if there would be these strange snow formations. I walked up the mountain a couple of times before I got the photos I wanted.

The day I made the photos in the book, I recorded the wind at about 62 miles per hour on the mountain top. I would take off my gloves just long enough to make a frame or two, then I’d have to warm them and my cameras under my coats.

You state int he book that the people who live along the mistral’s path in Provence have a “complicated relationship” with the wind. In what ways?

Order and tradition are an important part of life in France. Farmers tidy their fields. People don’t leave the house disheveled. They’re more buttoned up than Americans. There are generally accepted rules of behavior that can be confining. Along comes the mistral. It’s a nuisance that slams car doors, loosens gutters, and upturns plants. Imagine you’re a waiter carrying a tray of glasses at an outdoor restaurant during a mistral. Things happen. Ten glasses go crashing to the ground, well… [French shrug]. The mistral happens. Chaos happens. It’s liberating.

Tell me about the writings in this book–how you chose them.

Many writers over the years have been moved to write about the mistral, and I felt their words would enhance my images. Of course, I wanted to include the work of the great French writers and poets like Frédéric Mistral, Alfonse Daudet, and Jean Giono, who were from the region. I found it surprising that so many foreigners have been charmed by and in awe of the mistral, from Paul Auster to George Sand to Robert Louis Stevenson.

What did you start out wanting to accomplish through this book, and did it change any as your work progressed?

A long project like this reveals itself slowly. I always thought the mistral could be a lens through which I could observe and describe Provence, but, in doing the work, I saw the mistral is essentially the spirit of the place.

Rachel Cobb will be at Lemuria on Monday, October 29, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss Mistral: The Legendary Wind of Provence.

Comments are closed.