By Jim Ewing.

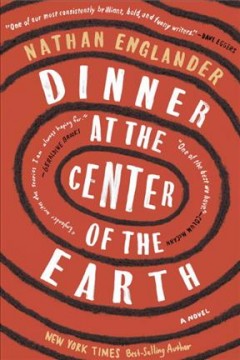

Nathan Englander’s Dinner at the Center of the Earth is more than a spy mystery. Rather, it’s a puzzle that starts off fuzzy and indistinct and ends crystal clear, spinning off into the confounding greater madness that is the Middle East conflict.

It starts off with seven main characters:

- Z, an American kept in secret prison;

- The General, who, though not named, is presumably Ariel Sharon;

- Ruthi, The General’s longtime aide, who is also the mother of Z’s prison guard:

- The Guard, who becomes Z’s friend as much as captor, or exists somewhere in the gray zone of Stockholm Syndrome;

- Joshua, a Canadian businessman;

- The Waitress, who becomes Joshua’s lover; and:

- Farid, a Palestinian businessman who funnels money to terrorists in his homeland.

The characters are built slowly, as the chapters flit between events in Germany, France, Italy, and Israel in 2002 and 2014. In the beginning, we don’t know the identity of Prisoner Z, or about the crime he committed to land him in prison.

The characters are built slowly, as the chapters flit between events in Germany, France, Italy, and Israel in 2002 and 2014. In the beginning, we don’t know the identity of Prisoner Z, or about the crime he committed to land him in prison.

The plot comes together like a Rorschach test: pieces of the puzzle becoming clear, almost as much from the reader’s memories and perceptions as the from deft touch of the author delineating the characters.

It slowly develops from specific events into a recognizable whole that, once realized, is complex and riveting as, midway through the novel, the deceptions and revelations become clear and the narrative picks up in real time.

We come to find that none of the characters we have come to know are truly who they say—or believe, or others believe—they are.

The “dinner” at the heart of the title is an event in the book, at its end, that may be seen as a metaphor for the muddle that is Midle Eastern politics, where right and wrong are often as blurred as the identities and possible motivations of the main characters.

And it may also be seen as a type of bizarre love story: where bitter rivals come to love each other, trust each other, need each other, even as they openly debate and sometimes wantonly deal death to the other.

Perhaps needless to say, Dinner is not your typical “spy” novel, as it begs more questions than it answers and spurs more honest soul searching than conventionally found in the genre. There are no “bad guys” here, no black and white hats, only shades of gray, tinged by unanswerable questions masking murderous norms.

Every character is flawed, vulnerable, in some ways endearing, and both a selfless hero and callous villain depending on one’s point of view.

All is relative. As Z tells the The Waitress when he confesses to her that he is a spy: “Some wrong things, in circumstances, are inherently right.”

But, as events unfold, the plot reveals that some possibly right things are inherently wrong.

Englander has put together a masterful spy novel that confounds conventions and will leave readers questioning the validity of their own convictions about right and wrong.

Jim Ewing, a former writer and editor at The Clarion-Ledger, is the author of seven books including his latest, Redefining Manhood: A Guide for Men and Those Who Love Them.

Comments are closed.