Since I’ve been working at Lemuria, I’ve self-imposed a rule of not writing about a book till I’ve finished it.

I am currently breaking that rule. Demolishing it. Splintering it without a shadow of hesitation or guilt.

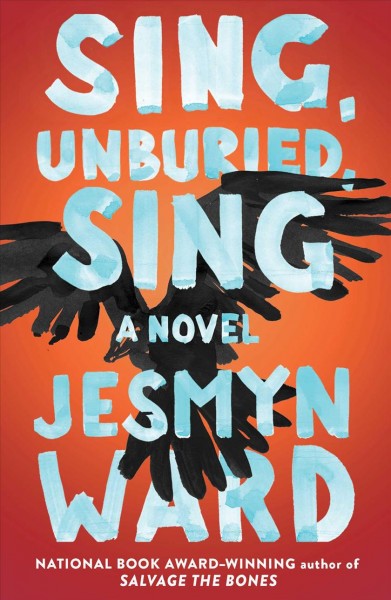

Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing is lots of things: brilliant, gorgeous, haunting, raw, tender, honest. Much like her National Book Award winner Salvage the Bones (a personal favorite of mine), Sing takes place in an impoverished area of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Both books’ characters find themselves in a mix of relationships—familial, internal, romantic—yet Sing is in no way a cookie-cutter redux of Salvage. Sing shifts through various first-person narrators, and does so in a way that’s easy to follow. If you’re having nightmarish flashbacks of Faulkner, don’t: these leaps between characters (mostly the 13-year-old, endearing Jojo and his difficult mother Leonie) aren’t pretentious displays of cleverness for its own sake. One of Ward’s gifts as a writer is a conspicuous wedge of human empathy. By getting into the mind of Jojo, we see his desire for toughness and tenderness, his need to be protector for his younger sister Kayla, and his longing to be a surrogate father for Kayla the way his own grandfather is for him. While Jojo lends us his frustration at his absent mother, the chapters from Leonie’s perspective help round her character. Her drug use isn’t entirely selfish—it’s her way of self-medicating the hurt of the violent death of her older brother. We see her doubting her own abilities as a mother, cursing herself, but trapped in her own self-doubt so as to prevent her from risking connection with her kids. Ward isn’t necessarily excusing Leonie’s behavior so much as she is explaining it, and showing us the complexity of the human heart in conflict with itself, to steal a phrase from Faulkner.

Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing is lots of things: brilliant, gorgeous, haunting, raw, tender, honest. Much like her National Book Award winner Salvage the Bones (a personal favorite of mine), Sing takes place in an impoverished area of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Both books’ characters find themselves in a mix of relationships—familial, internal, romantic—yet Sing is in no way a cookie-cutter redux of Salvage. Sing shifts through various first-person narrators, and does so in a way that’s easy to follow. If you’re having nightmarish flashbacks of Faulkner, don’t: these leaps between characters (mostly the 13-year-old, endearing Jojo and his difficult mother Leonie) aren’t pretentious displays of cleverness for its own sake. One of Ward’s gifts as a writer is a conspicuous wedge of human empathy. By getting into the mind of Jojo, we see his desire for toughness and tenderness, his need to be protector for his younger sister Kayla, and his longing to be a surrogate father for Kayla the way his own grandfather is for him. While Jojo lends us his frustration at his absent mother, the chapters from Leonie’s perspective help round her character. Her drug use isn’t entirely selfish—it’s her way of self-medicating the hurt of the violent death of her older brother. We see her doubting her own abilities as a mother, cursing herself, but trapped in her own self-doubt so as to prevent her from risking connection with her kids. Ward isn’t necessarily excusing Leonie’s behavior so much as she is explaining it, and showing us the complexity of the human heart in conflict with itself, to steal a phrase from Faulkner.

Ward’s fiction and nonfiction shows us the importance of personal, familial history, and how things from previous generations aren’t really all that previous. Her memoir Men We Reaped illustrates the struggle of generational poverty and quiet, systemic racism perfectly. The notion of inheritance manifests itself in Sing in a fascinating way: ghosts. I would never classify this novel as a fantasy/supernatural genre piece, nor do I think that is Ward’s intent. Leonie sees her dead brother, Given, but can’t hear him speak; Jojo meets his grandfather’s dead friend Richie, who tells him about their days in Parchman. The past isn’t past—another Faulkner phrase I’ll paraphrase—and the ghosts in Sing show us that. The myriad difficulties of poverty, compounded with the burdens of racism, are hard to get away from. They haunt their victims, float constantly over their shoulders, peek in-and-out of their vision, or sometimes present themselves in full view.

There’s probably more about the novel that this piece is missing. I’m halfway through the book, and as soon as I finish this post, I’ll open Sing, Unburied, Sing back up and skip sleep. The book’s that good. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll get back to it.

Comments are closed.