By Ellis Purdie. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (May 12)

When asked to read Barry Gifford’s Southern Nights for review, I agreed without hesitation. Though unfamiliar with Gifford’s (many) books, I had seen the films Lost Highway and Wild at Heart, both directed by David Lynch of Twin Peaks fame and penned by Gifford.

When asked to read Barry Gifford’s Southern Nights for review, I agreed without hesitation. Though unfamiliar with Gifford’s (many) books, I had seen the films Lost Highway and Wild at Heart, both directed by David Lynch of Twin Peaks fame and penned by Gifford.

If his novels were anything like his screenplays, I knew one thing for certain: they would not bore.

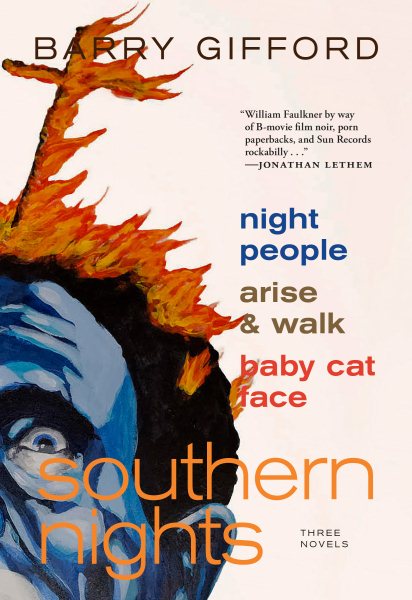

As of this review, I confirm, the three short novels in Southern Nights, comprised of Night People, Arise & Walk, and Baby Cat-Face will leave you awake at night, pulse racing, double-taking the shadows for Gifford’s people.

These novels are a howling freight train, lit up and pummeling full blast into the darkness. While reading them, I kept thinking of Flannery O’Connor, Barry Hannah, and William Gay: southern writers unafraid of depicting violence, the grotesque, the worst in the human heart.

Though the Chicago-born Gifford is not a “southern writer” proper as the three aforementioned, the setting for Southern Nights is the South, and the novels boast the wildest of Baptist preachers, unashamed deviants, drug peddlers, assassins, flying bullets, and the children who write letters to Jesus in effort to navigate such a relentless world.

At one point while reading Night People, I stopped and called a friend, saying, “If you haven’t read Barry Gifford, go grab this book right now. In the section I just finished, a woman drives over to her husband’s lover’s house, shoots them both, then drives her car into a wall of the Reach Deep Baptist Church, dying upon impact. This is the real stuff.”

In terms of plot, the novels in Southern Nights skirt an overarching narrative, focusing instead on several smaller narratives within the same setting. The last section of Night People, for example, tells the story of a young girl, Marble Lesson.

Marble’s father, Wes, is down on his luck, recently divorced, and in need of work. The story begins with Marble’s leaving New Orleans to live with her mother in Florida.

However, upon hearing of her father’s suffering without her, Marble hitches a ride with a transgender woman who, after some of the most charming dialogue I have read in some time, puts Marble on a plane back to Louisiana.

What follows is fireworks: Wes getting involved with a drug cartel, taking Marble with him to meet his new employer, an assassin showing up with ill intentions, and Marble’s encounter with said assassin that leaves him artfully dead on the floor.

In another episode in Arise & Walk, two characters wait in a hotel room for their purchased dates.

When the women arrive, the men, Wilbur “Damfino” Nougat and Gaspar DeBlieux (Gifford consistently uses the best names), quickly realize they are getting something other than what they paid for. The scene is hilarious, disturbing, and searingly original. Again, guns are involved.

These are only two narratives out of a 452-page book chock-full of thrilling madness. Interestingly, while there are stories of some length in the book, Gifford writes such that you can turn to almost any chapter and read something interesting.

The chapters feel both like the continuation of a novel as well as flash fiction pieces that stand on their own. Like flash fiction, the chapters are short, making each novel a brisk whirlwind of an experience.

These novels are haymakers: stunning, brutal, not for the faint of heart. I greatly admire Gifford’s honesty, his “going there” in these works with no fear.

After Southern Nights, I will be reading Gifford’s Sailor and Lula novels, his books of poetry, and even his nonfiction on horse-racing. Gifford has the goods, and he delivers.

Ellis Purdie is a graduate of The Center for Writers at The University of Southern Mississippi. He lives with his family in Marshall, Texas.

Barry Gifford will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, May 22, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss Southern Nights.

Comments are closed.