By DeMatt Harkins. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 17)

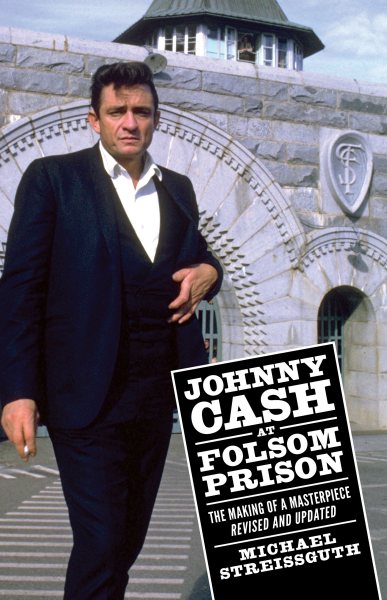

The morning of January 13th, 1968, Johnny Cash rode half an hour from Sacramento to the granite walls of Folsom State Prison. With Carl Perkins and The Statler Brothers as openers, he played two shows at 9:40am and 12:40pm. The composite recording of the proceedings would surpass 3 million units sold.

The morning of January 13th, 1968, Johnny Cash rode half an hour from Sacramento to the granite walls of Folsom State Prison. With Carl Perkins and The Statler Brothers as openers, he played two shows at 9:40am and 12:40pm. The composite recording of the proceedings would surpass 3 million units sold.

This was not Cash’s first performance at a prison, nor was it his initial appearance at that particular location. But in Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison: The Making of a Masterpiece, Michael Streissguth details what proved to be the most important day of Cash’s career, providing the trajectory to cement his place in musical history.

If you came up during a time when Cash was already a living legend, it is natural to assume he always was one. However, Streissguth explains this was not the case. At Folsom Prison‘s namesake track was recorded at Sun Studios 13 years prior. With the exception of one outlier, Cash’s string of hits tapered off around 1963. His output became increasingly uneven and uninspired. This came as no surprise with recording sessions regularly pilfered, when not missed entirely.

Streissguth lays this rut at the feet of Cash’s drug addiction. Throughout the decade, the singer would struggle with the misuse of amphetamines. Meeting concert obligations became a 50/50 prospect. When he did make it to the microphone, it was not unusual for Cash to be deep in the throes of his habit or just returning to consciousness.

However, as the 60s drew to a close, Streissguth demonstrates two people came into Cash’s life, to great benefit. They would help set the stage for the success of At Folsom Prison. Country royalty June Carter served as a calming, supportive, and loving influence on the troubled soul. Her budding relationship with Cash spawned not only a marriage, but also a return to form in the Grammy-winning duet “Jackson.”

Simultaneously, when Columbia Records transferred Bob Johnston to run their Nashville operations, it would open doors for Cash. Although the Bob Dylan and Simon & Garfunkel producer had been stationed in New York, the native Texan proved a Cash ally, with an equal penchant for mischief. Cash had been asking to record at a prison for years. Johnston was just the guy to ignore the home office’s warnings and green light such a project. The gamble would pay off for all parties involved.

Just as At Folsom Prison would provide Cash’s career a shot in the arm, it also rehydrated country music from its own drought of sorts. In 1968, the musical order of the day was psychedelic and soul. Streissguth argues that Cash was miscategorized as country front the get-go, since he truly played rockabilly. He contends the popularity of Folsom greased the wheels for an updated country/rock hybrid introduced by The Flying Burrito Brothers, The Byrds, and Buffalo Springfield. Going further, Streissguth credits Cash’s revival and subsequent exponential growth for paving the way to arena success for Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, among others.

Nonetheless, Streissguth asks the question, why is At Folsom Prison rarely if ever included in the best albums of the rebellious 60s? While LPs still considered masterpieces today explored new artistic landscapes, he asserts none of them truly challenged authority like At Folsom Prison. Mocking guards and swearing in front of a thousand inmates as tape rolled was a bold move for the era.

Recognizing this, Columbia built their marketing strategy on Cash’s impudence. At the time, the company allocated their promotional budget to pop and classical. With limited resources and a seemingly countercultural message, Columbia sent the record straight to underground newspapers and free-form radio DJs. Although now considered a landmark country album, At Folsom Prison initially gained momentum with the hip set.

But as Streissguth points out, Cash went beyond merely thumbing his nose. Over the next decade he would become an outspoken advocate for prison reform. Essentially unheard of at the time, he understood that caring for prisoners would achieve more for society than brutality. For years he spoke out during interviews, and even appeared at a Senate hearing in 1972.

Without question, At Folsom Prison put Johnny Cash back on the map for three more decades. In addition to putting you there that chilly morning in 1968, Streissguth places the album in context of Cash’s career, personal life, and music as a whole.

DeMatt Harkins of Jackson enjoys flipping pancakes and records with his wife and daughter.

William H. (Bill) Morris would tell you that he has had more than his share of “magic moments’ in his lifetime, and he shares many details of his close-knit friendships with some of the greatest musicians of the R & B, Rock and Roll and Doo-Wop era of the ‘50s and ‘60s in his heartfelt memoir,

William H. (Bill) Morris would tell you that he has had more than his share of “magic moments’ in his lifetime, and he shares many details of his close-knit friendships with some of the greatest musicians of the R & B, Rock and Roll and Doo-Wop era of the ‘50s and ‘60s in his heartfelt memoir,

A member of the Blues Hall of Fame, Waterman managed, booked, and/or photographed essentially the entire Delta Blues revival as well as the electric blues apex of the 60s. Who else could write B.B. King’s biography, introduce unreleased Robert Johnson tracks to Eric Clapton, or receive an apology from Bill Graham? Guided by his level head and committed heart, Dick made many allies and musical history.

A member of the Blues Hall of Fame, Waterman managed, booked, and/or photographed essentially the entire Delta Blues revival as well as the electric blues apex of the 60s. Who else could write B.B. King’s biography, introduce unreleased Robert Johnson tracks to Eric Clapton, or receive an apology from Bill Graham? Guided by his level head and committed heart, Dick made many allies and musical history.

As a reader and an avid music listener, I am drawn to the memoirs of musicians that I listen to the most or that I have a preconceived notion of. This is usually because I am interested in learning about these musician’s lives outside of how they portray themselves through the music they make. However, my introduction to former musician Viv Albertine was not through her music with her legendary punk band

As a reader and an avid music listener, I am drawn to the memoirs of musicians that I listen to the most or that I have a preconceived notion of. This is usually because I am interested in learning about these musician’s lives outside of how they portray themselves through the music they make. However, my introduction to former musician Viv Albertine was not through her music with her legendary punk band  The Jazz Pilgrimage of Gerald Wilson

The Jazz Pilgrimage of Gerald Wilson Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown

Jim Dickinson and wife Mary Lindsay dine with Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler, famed producer Tom Dowd, Dr. John, and Mick Jagger at a Clarence Carter show. Was this a typical social occasion for Dickinson? Hardly. But his posthumous memoir,

Jim Dickinson and wife Mary Lindsay dine with Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler, famed producer Tom Dowd, Dr. John, and Mick Jagger at a Clarence Carter show. Was this a typical social occasion for Dickinson? Hardly. But his posthumous memoir,