Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (October 21)

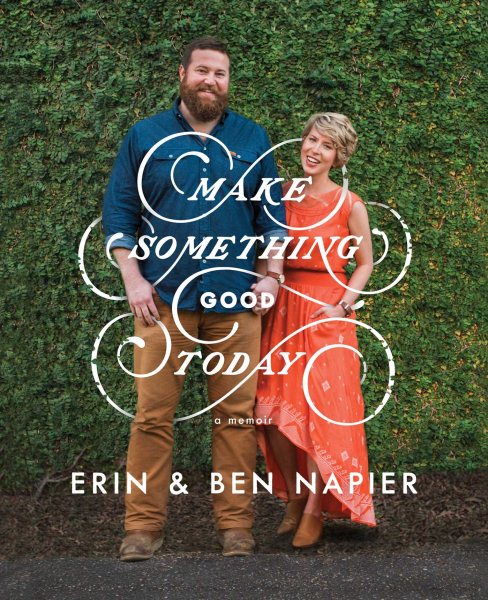

Erin and Ben Napier’s passion for home renovation is obvious on every episode of their HGTV show Home Town, where they take on dilapidated, vintage houses in every stage of disrepair and create cozy homes in their own home town of Laurel.

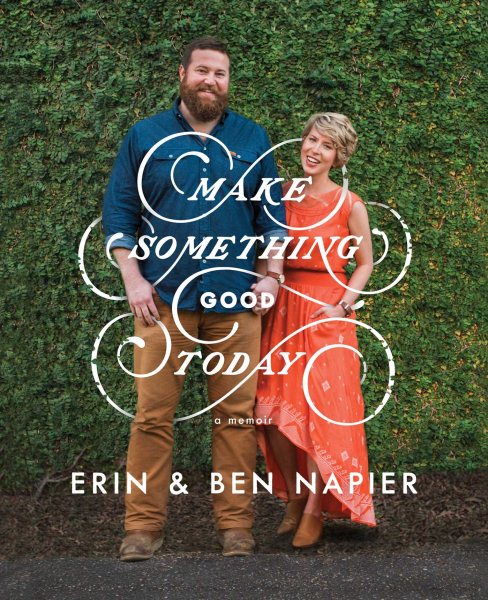

How the couple has gotten to this point is the result of two lifetimes of struggles and triumphs as documented in their memoir, Make Something Good Today. Through 18 inspiring chapters, husband and wife take turns sharing their stories–complete with hopes and fears–but always filled with encouragement. The book also includes dozens of family photos and hand-painted sketches by Erin.

How the couple has gotten to this point is the result of two lifetimes of struggles and triumphs as documented in their memoir, Make Something Good Today. Through 18 inspiring chapters, husband and wife take turns sharing their stories–complete with hopes and fears–but always filled with encouragement. The book also includes dozens of family photos and hand-painted sketches by Erin.

College sweethearts since their years as students at Jones Junior College and then at Ole Miss, Erin is a designer and entrepreneur who established her own international stationary company; and Ben is a mater woodworker and businessman who founded Scotsman Co., and is a co-owner of Laurel Mercantile Co. in Laurel. Together, they’re known nationally for their home restorations in Laurel. The couple welcomed their first child, affectionately known as “Baby Helen,” in January.

Erin, you grew up in Laurel; and Ben, as a Methodist minister’s son, you moved around to several different communities during childhood. After your years together in college and earning your degrees at Ole Miss, what brought you back to Laurel after you got married?

Erin and Ben Napier

Erin: I had roots there, my family, and Ben had been part of that family pretty much since the week we met so it felt like for him, too, even though his family is scattered across the state. It felt right to build a life we wanted in the place where we had so much to come back to.

Ben: Yeah, I’ve always said I fell in love with Erin and fell in love with Laurel at the same time. They seemed one in the same to me. And we both were offered jobs there, so it felt like a stable, adult decision.

How did you come to see the potential for a much brighter future for this small town?

Erin: I saw that our group of friends who all had come back home to Laurel after college–the Framily, we call it–had very specific gifts and talents that worked so nicely together. Ben and I were like the mascot and the art department, and I now see the way we shared our town on social media and my blog a form of producing. We were being creative directors of the image of our town, and I think that’s the job of any creative–to tell the world at large what is cool. To give people permission to believe in something that may have been considered lame or boring before.

Ben: And when we all stay in our own lanes, magic happens. If we let the finance people find the grants and financial support, and we let the folks with connections build the volunteer base, and we let the churches create family-centered events, and let the musicians plan the music festivals, it all comes together, and a town comes back to life. It takes all of us doing what we do best in one concerted effort.

Erin, tell me about the blog you started, and how it came to bring about such a turning point in your lives.

Erin: When I left my day job and started my own company, I was paralyzed with fear and worried I would fail. writing each day was a way to focus on the blessings, on the good in the aftermath of the difficult. It became so important to me, I began to cling to the good and it shifted the way I thought about everything. I would make something good happen if it looked like I would have little to say at the end of the day. It was an exercise in editing out the messiness of life and focusing instead on gratitude. For eight years, 2010-2017, I did not miss a single day.

Tell me about obstacles you’ve had to navigate as you worked so hard to realize your dreams.

Ben: There’s always uncertainty when changing careers, which we’ve been through several times, and there is always going to be the challenge of changing hearts and minds of those who have always lived here and decided to obstinately refuse to believe that Laurel can improve and be a special place again.

And, there’s a handful of soreheads who feel Erin and I get too much credit for all this, and they are probably right. We’re just having fun and hoping to inspire folks around us as we go. It’s like a game, to see how far we can take this thing. This movement, of sorts.

How has your faith played a role in bringing you to where you are now, and sustaining you through hard times?

Ben: Faith has been part of my life for as long as I have been alive, and it’s the guiding hand in every decision we make together as a family.

Erin: When I wonder why in the world this is happening to us of all people in the world, I know that it’s God authoring the story, and that gives me comfort in it. To know that we’re being used for something he has ordained, for however brief or long-term this whole thing may be, makes me feel like we can do this. Otherwise, i would feel too small and too unimportant to have this kind of spotlight.

In your wildest dreams, I doubt either of you planned to be national TV stars, but you both seem to embrace it naturally! How has that changed you? What has it taught you?

Erin: Ben was made to be the center of attention. He’s very comfortable with it. Not in a showy way, just in a way that he can shoulder attention and make it look effortless. I’m introverted, so having this very public career is a little uncomfortable for me. But as long as I only think about our crew that we work with every day, whom we’re so close to, it feels like we’re just messing around, making a little short film for local viewing only. I can’t think about what it really is too much. It’s like looking at the sun, and it’s too much!

It’s taught me to guard things in our life, to keep them sacred and close, like the friends we had before all this happened, and Helen. I want to keep her protected and unaware of the public-ness of our job as much as we can.

You both have entrepreneurial spirits. Tell me about the businesses you’ve built individually and together.

Ben: Erin began her letterpress wedding stationary company in 2008, and a few years later we started an online shop called ErinAndBen.co of antiques, my furniture, and American-made goods to give us a boost during the holiday season when wedding traffic would die down.

When the show started, we realized we couldn’t do them by ourselves anymore, and our four best friends–Jim, Mallorie, Josh, and Emily–came on as partners, and ErinAndBen.co became Laurel Mercantile Co., and my hobby woodworking outfit, Scotsman Co., became the flagship brand of LMCo.

Josh bought a building downtown and renovated it to become our first brick and mortar shop for the Mercantile; and this year, another building, which became the Scotsman General Store and Woodshop.

We only sell American-made goods because if we’re going to be serious about revitalizing small-town America, then we have to be serious about making things in America to keep our hometowns strong. There are challenges to sourcing and manufacturing everything in the USA, but we believe it’s worth it.

There’s pride in the things we make. The true cost of a bargain is in the loss of jobs and thriving communities in small town America. In January, our collaboration with Vaughan-Bassett will be in stores everywhere, a line of furniture made by 600 American craftspeople in Virginia, made from Appalachian hardwoods.

You both seem to possess a wisdom beyond your years, and you’ve even written your story as a memoir. What is your biggest message of this book, and what do you think the future holds for you and for the city of Laurel?

Erin: It’s a love story, and it’s a bout blooming where you’re planted. It’s about how we s tarted looking at what was right were we were standing instead of what was wrong. Southerners, I think, are especially good at taking what we have, however modest it might be, and making something delicious or beautiful from it. There is no secret to how it’s done. It’s just about changing our way of seeing.

I don’t know what the future holds for Laurel, but I hope it doesn’t rely too much on a TV show. I hope the seeds we’ve been planting in this town for the last 10 years will bear fruit for generations to come. I hope the pride we see in this town takes root and holds steady, for good.

Erin and Ben Napier will be at Lemuria on Saturday, October 27, at 2:00 p.m. to sign Make Something Good Today, and will read from it starting at 4:00 p.m.

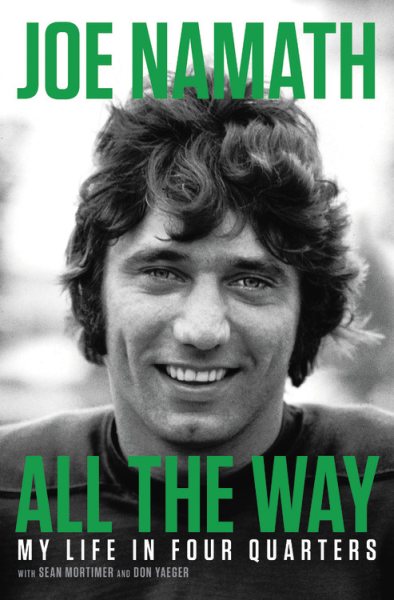

What was going to talk about here? Oh, yes. Joe Namath. Joe Willie. Broadway Joe. And, specifically, his new memoir, All the Way: My Life in Four Quarters.

What was going to talk about here? Oh, yes. Joe Namath. Joe Willie. Broadway Joe. And, specifically, his new memoir, All the Way: My Life in Four Quarters.

And yet. As Hungary and the citizens of the Engels’ town of Pecs, Hungary were overrun by Nazi forces in 1944, a century of prominence, good works and assumed assimilation weren’t enough for the Engels. The scion of the Pecs branch of the family—McMullan’s grandfather’s first cousin Richard Engel—died at the Mauthausen concentration camp after being rounded up along with other town Jews in March 1944. The story of Richard’s descent from respected, wealthy World War I war hero and city civic leader to being marched off as townspeople watched is the spellbinding story that McMullan tells in

And yet. As Hungary and the citizens of the Engels’ town of Pecs, Hungary were overrun by Nazi forces in 1944, a century of prominence, good works and assumed assimilation weren’t enough for the Engels. The scion of the Pecs branch of the family—McMullan’s grandfather’s first cousin Richard Engel—died at the Mauthausen concentration camp after being rounded up along with other town Jews in March 1944. The story of Richard’s descent from respected, wealthy World War I war hero and city civic leader to being marched off as townspeople watched is the spellbinding story that McMullan tells in

“I don’t know how many people were kidnapped in Mississippi in 1968, but I was one of them,” writes author Lovejoy Boteler in the first sentence of the

“I don’t know how many people were kidnapped in Mississippi in 1968, but I was one of them,” writes author Lovejoy Boteler in the first sentence of the  Louisiana native and journalist Ken Wells fondly recalls what he and his five brothers called “the gumbo life” in rural Bayou Black–a lifestyle lived close to the land and that meant he would not see the inside of a supermarket until he was nearly a teenager.

Louisiana native and journalist Ken Wells fondly recalls what he and his five brothers called “the gumbo life” in rural Bayou Black–a lifestyle lived close to the land and that meant he would not see the inside of a supermarket until he was nearly a teenager.

Like most millennials making connections in 2018, I found Jedidiah Jenkins through social media. As the editor of Wilderness magazine, Jedidiah filled

Like most millennials making connections in 2018, I found Jedidiah Jenkins through social media. As the editor of Wilderness magazine, Jedidiah filled  His new book, Heavy: An American Memoir (Scribner) is, literally, a long letter written directly to his mother, as he works through the complexity of his disordered childhood and its continued effects on his life today. The result is a deeply personal, and open, cry for answers as to why theirs was such a difficult relationship even as she unfailingly reassured him of her love.

His new book, Heavy: An American Memoir (Scribner) is, literally, a long letter written directly to his mother, as he works through the complexity of his disordered childhood and its continued effects on his life today. The result is a deeply personal, and open, cry for answers as to why theirs was such a difficult relationship even as she unfailingly reassured him of her love.

Key has returned with a metatextual sequel called

Key has returned with a metatextual sequel called  How the couple has gotten to this point is the result of two lifetimes of struggles and triumphs as documented in their memoir,

How the couple has gotten to this point is the result of two lifetimes of struggles and triumphs as documented in their memoir,

He brought a rig with a custom decorative wrap on the trailer. It looked awesome. Alas, I was visiting my brother in Nashville at the time.

He brought a rig with a custom decorative wrap on the trailer. It looked awesome. Alas, I was visiting my brother in Nashville at the time. This gives Murphy an unexpected vantage point: he certainly illuminates his world on the highway; I could see into the cabs of trucks from the Greyhound bus I was riding. Cummins, a diesel engine manufacturer whose existence I had spent decades being oblivious of, had a headquarters in Indianapolis that I noticed immediately upon arrival.

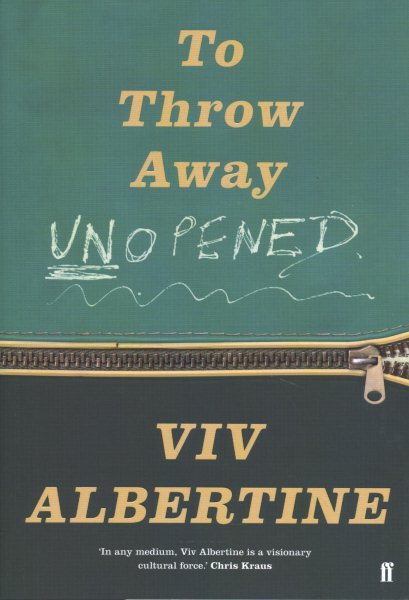

This gives Murphy an unexpected vantage point: he certainly illuminates his world on the highway; I could see into the cabs of trucks from the Greyhound bus I was riding. Cummins, a diesel engine manufacturer whose existence I had spent decades being oblivious of, had a headquarters in Indianapolis that I noticed immediately upon arrival. As a reader and an avid music listener, I am drawn to the memoirs of musicians that I listen to the most or that I have a preconceived notion of. This is usually because I am interested in learning about these musician’s lives outside of how they portray themselves through the music they make. However, my introduction to former musician Viv Albertine was not through her music with her legendary punk band

As a reader and an avid music listener, I am drawn to the memoirs of musicians that I listen to the most or that I have a preconceived notion of. This is usually because I am interested in learning about these musician’s lives outside of how they portray themselves through the music they make. However, my introduction to former musician Viv Albertine was not through her music with her legendary punk band