Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 8)

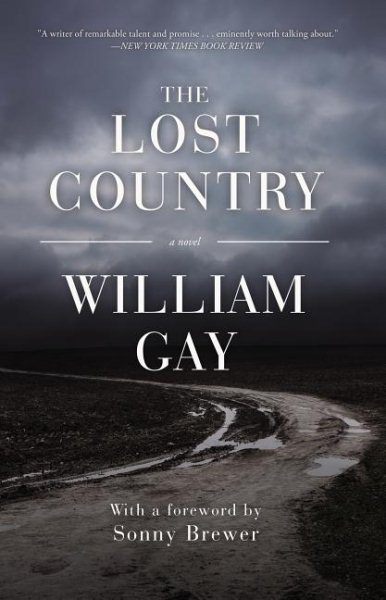

The legacy of William Gay–who became an iconic Southern Gothic writer after beginning his career as a published novelist in his late 50s–is alive and well with the posthumous release of one of his last novels, The Lost Country.

Fortunately for his fans, Gay’s longtime friend, editor, and road trip buddy, Sonny Brewer of Fairhope, Alabama, is taking the new book on tour himself.

Fortunately for his fans, Gay’s longtime friend, editor, and road trip buddy, Sonny Brewer of Fairhope, Alabama, is taking the new book on tour himself.

True to Gay’s memorable style, The Lost Country is classic Gothic at its best: downtrodden characters who continue to suffer defeats, blended with a show of violence and a haunting sense of sadness as they struggle for redemption.

After the publication of his prize-winning first novel, The Long Home in 1999, Gay went on to add Provinces of Night, I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down, Wittgenstein’s Lolita, and Twilight to his list of successes–after spending the previous four decades as a construction worker, house painter, factory worker, and TV salesman. He died of an apparent heart attack in 2012.

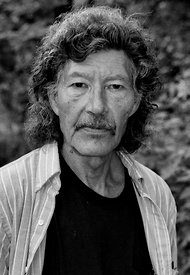

Sonny Brewer

Brewer, who wrote the foreword to The Lost Country, has spent much of his career in the roles of publisher and/or editor for a newspaper and a number of magazines and other publications, including the Eastern Shore Quarterly, The Southern Bard, and the Red Bluff Review.

His the author of four novels: The Poet of Tolstoy Park, A Sound Like Thunder, Cormac, and The Widow and the Tree. He also edited the widely known Blue Moon Café anthology series.

Tell me about your relationship with William Gay and how this book tour came about.

The publisher asked me if I would tour with this book and I said yes. The main reason for the request, I think, is because I was editor-in-chief at MacAdam-Cage Publishing at the time of William’s death, and the book was under contract there. A big search found only some 250 handwritten pages from the manuscript (which had been lost). I read those pages and had to deliver the disappointing news to the publisher that about half the book was missing.

So, my early involvement with the manuscript was part of why I was asked to help the book on the road. The other part was my friendship with the author. I write about how I met William in the foreword included in The Lost Country, so I’ll leave that bit for readers who get the book.

William Gay

But, I’ll say that I was instantly drawn to him in a way that had little to do with his writing, or his looming celebrity. He was a good man. Unassuming, honest, self-effacing, funny, intelligent, generous, and on and on. What was remarkable to me was how strongly and deeply he conveyed those qualities at a glance. It’s sort of like the old saw about judging the qualities of a man from the shoes he wears–which is inaccurate, but not ridiculous. Our faces and our eyes tell the story of who we are. And William was a good story.

Why was The Lost Country said to have been “anticipated for a decade”?

William first spoke publicly of the novel’s existence long before its release here in 2018. He read from its pages at literary conferences and at bookstores. But the whole manuscript was missing, and there’s a suggestion that he simply couldn’t remember where he’d put it for safekeeping. I can believe that because I recently failed to find a screenplay I had written. I had my sister looking and a friend looking. We never found the original. But a movie producer friend has a copy on his computer. I was too embarrassed to ask him for a long time.

Gay’s writings are noted for their trademark elements that make up true Southern Gothic writings, including mostly rural and often eccentric characters whose lives are trapped in poverty, crime, violence, and hopelessness. What, in your opinion, draws readers to Southern Gothic literature?

I was recently asked why I thought 125 readers bought Fifty Shades of Gray, and I said it must be good, on some level.

I think you want to know on what level are Southern Gothic stories and novels found to be a good read, and I would say for those readers they find settings, situations, circumstances, events, and characters that stir in them emotions of fear and love, of empathy and wonder, of curiosity, and find in the whole of their reading experience a common bond of humanity that wobbles along between the ditches of a highway taking us all someplace, to the same place of truth. And the company of these others, like us, that we find in these books helps to fend off loneliness.

In The Lost Country, set in rural Tennessee in 1955, main character Billy Edgewater seems to be a magnet for attracting troubles and aligning himself with the wrong people, as if his own bad decisions are not enough to add to his despair. It seems that Gay had a a gift for creating harsh stories yet offering them in a beautifully literary form. How would you describe his work, and his writing style?

I was a used bookseller, owned a store in Fairhope called Over the Transom Books, and I had some volumes that were collectible and pricey. When I found a first edition of To Kill a Mockingbird worth several thousand dollars at a yard sale, a colleague in Florida told me there’s a distinction among antiquarian booksellers between scarce and rare. A scarce book comes along once in a few years. A rare book like the one I’d lucked up on comes along once in a lifetime. William Gay’s literary talent, his work, and his writing style, and, indeed, the kind of man he was, is like that. Rare.

Tell me about Gay’s personality, what motivated him, how he became so interested in the Southern Gothic genre, etc.

William told me about a middle school English teacher who “saw something” in him and handed him a copy of Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel. It was not a homework assignment. There would be no test. The book was a gift. And, by grace, something in that book plumbed the depths of his soul and discovered there a gift in him.

He told me that he read twice, before he turned 14, that 544-page book. Had he found in Eugene Gant a version of himself? Had William found in Wolfe’s dense prose writing that he believed he wanted to imitate? I don’t know. We didn’t talk about that. But William, it was apparent, did fall in love with words, their rhythm, their cadence, their flow, and had from reading an experience that electrified him and drove him to an addiction for the masterworks of Southern writers. And when he set his own pen to paper he became able to match them word for word in power and beauty.

I read to William a paragraph from his novel The Long Home and asked him about how long it took him to compose those sentences that staggered me when I first read them. He told me only as long as it took for him to write them down longhand because he had already crafted that paragraph and others during an eight-hour day hanging Sheetrock. How he didn’t cut off a finger with a hawkbill knife, I don’t know. William also said he could do that because he had a photographic memory. Which gift he also employed in the recall of long passages from his favorite books and that he could quote word-for-word. William Gay was called to be a writer, pure and simple. And, pretty as a song, he answered.

Are there other “lost” stories or novels by William Gay that are in the works for publication?

William’s home was robbed and vandalized while he was out of town doing a reading someplace. He told me his music CDs and his movie DVDs were slung out the back door and down the hill behind his place. He told me a box of his writing was stolen, and it included a completed novel manuscript on the bloody days of the Natchez Trace.

I asked him did he think we’d someday get it back as a posthumously published novel. He said no. He told me that he didn’t write sequentially, and some times forgot to number loose pages. He might write a scene from the end of a book at the beginning of a manuscript, for instance. “Nobody could put it together but me,” he said. Plus, the thief could be easier named if it comes out of hiding. I expect, too, however, there could be clemency granted the perpetrator if fans of William Gay had verdicts to cast.

Gay’s talent as a writer has been compared to that of William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Cormac McCarthy. Why is that, and do you believe that is an accurate assessment of Gay’s work?

I don’t like questions about comparisons between William’s writings and these three authors. It’s not unfair to ask. But the answer is readily available to those who read the books of Faulkner, and O’Connor, and McCarthy, and William Gay, or, at least from such reading an answer is personally well-formulated. Anyone who hasn’t read these writers does not care what I have to say. Nor, in fact, do those who have enjoyed the work of these masters.

Anything I didn’t ask that you’d like to include?

It should be said, for the record, how William was utterly devoted to his kids. Laura, and Lee, and Chris and William, Jr. drew a damn fine daddy.

Sonny Brewer will be at Lemuria on Tuesday, July 10, at 5:00 to sign and discuss The Lost Country by William Gay.

Comments are closed.