By DeMatt Harkins. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 28)

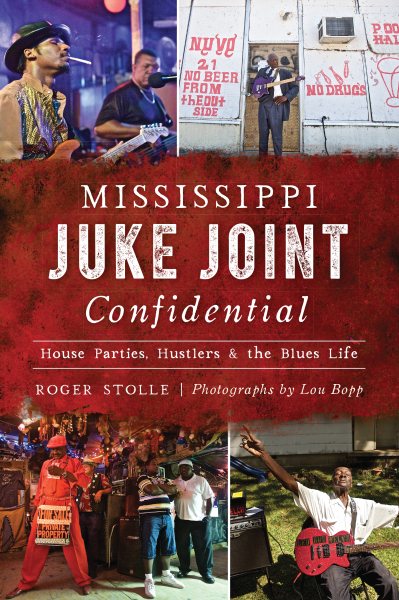

Over the past century, blues music has evolved while nonetheless retaining its core elements and purpose. In Mississippi Juke Joint Confidential, Roger Stolle, accompanied by photographer Lou Bopp, demonstrates this is equally the case with its archetypal venue.

Early in the millennium, Stolle moved from St. Louis to Clarksdale to open Cat Head music shop. Since then, he has gone on to start the annual Juke Joint Festival, produce several artists’ records and tours, become a contributing editor for Delta Magazine, deejay locally and on satellite radio, helm a trio of blues documentaries (We Juke Up In Here, M is for Mississippi, and Hard Times) and host the web series Moonshine and Mojo Hands.

Early in the millennium, Stolle moved from St. Louis to Clarksdale to open Cat Head music shop. Since then, he has gone on to start the annual Juke Joint Festival, produce several artists’ records and tours, become a contributing editor for Delta Magazine, deejay locally and on satellite radio, helm a trio of blues documentaries (We Juke Up In Here, M is for Mississippi, and Hard Times) and host the web series Moonshine and Mojo Hands.

In his follow-up to Hidden History of Mississippi Blues, Stolle begins by clarifying that self-declaration does not a juke joint maketh. Spots such as the Blue Front Cafe in Bentonia, Roosters in Sardis, Junior Kimbrough’s in Marshall county, The Subway Lounge in Jackson, The Do Drop Inn and Sarah’s Kitchen in Clarksdale, and Po Monkey’s out from Marigold all earned the distinction. These clubs are less refined, more raw. Many may not be up to code, let alone legal businesses.

Juke joints initially popped up as the lone secular, social outlet during Mississippi’s sharecropping era. They hosted such legends as Charley Patton, Robert Johnson, and Son House. Today’s equally sensational Mississippi juke joint musicians live practically off the cultural grid. But that doesn’t mean they don’t pack ‘em in.

While patrons most certainly feel the music in a Mississippi juke joint, they may not necessarily be able to see the band. As Stolle points out, contemporary juke joints tend to be paeans to resourcefulness. With that comes architectural and design anomalies. The band may be around a corner from half the crowd, or even placed in front of a bathroom. Not to mention, the look of the place may be spare or a collage of bygone marketing campaigns, amateur signage, and Christmas lights. Despite unconventional layouts and incongruous styles, juke joints function as the means to a musically euphoric end.

At the heart of Mississippi Juke Joint Confidential is a pair of chapters sourced from many of Stolle’s interviews with owners and musicians. The raconteurs include T-Model Ford, Terry “Harmonica” Bean, Sam Carr, RL Boyce, Lightning Malcolm, Mary Ann Action Jackson, Robert Belfour, Sarah Moore, James Super Chikan Johnson, LC Ulmer, and the legendary Honeyboy Edwards, among others. Collectively they paint a vivid picture of this underground musical scene—often with head-shaking hilarity.

Most people have seen guitars played on stage. Few have seen them used to defend a mid-performance knife attack. Also presented here is sage advice against chugging a pint of gin, right before playing the first song. Which juke joint is referred to as The Bucket of Blood? And perhaps everyone needs to visit the juke joint whose house chicken dances and drinks beer.

In addition to the high jinx, also evident are hard workers simply trying to provide a service to the community. Proprietors such as Red Paden and Sarah Moore echo they are not in it for the money. They recognize everybody needs a place to let it all hang out.

Several of Stolle’s subjects reminisce about juke joints’ days of yore. John Horton explains his preference for the old solo acoustic acts because it’s a greater feat to hold an audience’s attention, all night, by yourself. Along those lines, Jimmy Duck Holmes points out why blues was hollered—musicians were contending with a full room of revelers without the benefit of a sound system. And one can only imagine how raucous the Harlem Club in Inverness became when young David Lee Durham was relegated to peeking in the window to catch a set by Howlin Wolf or Muddy Waters.

Stolle additionally expounds on the cultural significance of moonshine, the profound history of Clarksdale’s Riverside Hotel and Bay St. Louis’ 100 Men DBA Hall, Bilbo Walker’s long journey from musician to juke joint operator, and the ins-and-outs of traveling internationally on blues tours.

Although juke joint music is known around the globe, Stolle and Bopp offer not only a peek into, but also an itinerary for what cannot be replicated outside of Mississippi.

DeMatt Harkins of Jackson enjoys flipping pancakes and records with his wife and daughter.

Roger Stolle will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival August 17 as a participant in the “Mississippi Blues” panel at 4:00 p.m. at the Galloway Foundery.

Comments are closed.