By DeMatt Harkins. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 8)

In September of 1984, Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got to Do with It” topped the US singles chart, as Prince’s “Purple Rain” dominated the album chart. Meanwhile in Belgium, four recording sessions from The Great Depression were the order of the day. That month, scholars descended upon Liège University for the International Conference on Charley Patton. The occasion marked the 50th anniversary of the pivotal Mississippi Blues legend’s passing.

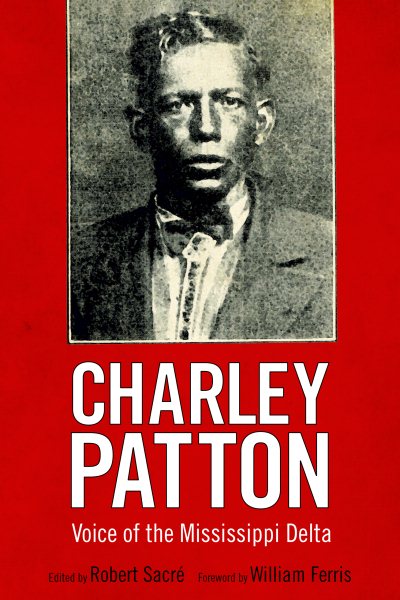

Charley Patton: Voice of the Mississippi Delta compiles nine presentation transcriptions from that forum. Each piece, some revised or amended, explores the man who brought us “Pony Blues,” and “High Water Everywhere,” as well as his ripple effects.

Charley Patton: Voice of the Mississippi Delta compiles nine presentation transcriptions from that forum. Each piece, some revised or amended, explores the man who brought us “Pony Blues,” and “High Water Everywhere,” as well as his ripple effects.

Seven years after the conference, while attending a proper headstone dedication in Holly Ridge, Mississippi, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s John Fogerty compared Patton’s body of work to the Dead Sea Scrolls. Significantly, Charley Patton is the earliest Delta Blues musician with a known history.

Born in Bolton, Mississippi, Charley Patton moved with his family to the atypically egalitarian Dockery Farms near Drew. In the Delta, he excelled as a prolific musician, master showman, and regional celebrity. Although only one photo exists of a sharply appointed Patton, he recorded 71 songs from 1929 to 1934.

These songs were heard and seen by the Mississippians who migrated north forging the first guard of Chicago Blues. Expats Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Elmore James would later leave their mark on yet a younger generation, domestically and abroad. The direct line of influence from Charley Patton is evident, and the impact is profound. Hence, the legion at Liège.

Robert Sacré not only organized the Conference, but also edited Charley Patton: Voice of the Mississippi Delta. The professor at the host university opens with a primer of traditional African music’s journey to the 20th century South. Arnold Shaw follows with comparisons of Patton to fellow Blues stalwarts, Bukka White, Son House, and Robert Johnson. The common thread being self-exploration. Focusing on the individual and not the collective was brand new with post-emancipation African American music.

University of Memphis’ David Evans’ piece provides a thorough Patton biography, replete with updates culled from interviews conducted since 1984. He thoughtfully surveys Patton’s life, recordings, spirituality, relationships, and identity. Evans seeks to understand how a Blues musician simultaneously stayed a juke joint draw while remaining the go-to party act for adults and children, black or white. From there a second Liège professor, Daniel Droixhe, analyzes the mechanics of the famous cannon through Patton’s chord and lyrical structure.

Pivoting to the effect of Patton’s music, noted Louisiana music author John Broven demonstrates how Delta Blues traveled south to Baton Rouge. Similarly, through 16 songs, Mike Rowe traces the progression of Blues from an acoustic Delta style to an electric Chicago style.

Having befriended Howlin’ Wolf in the late 1960s, Chicago journalist Dick Shurman recalls the last years of a musician who genuinely studied at the feet of Charley Patton. An invaluable viewpoint follows from Luther Allison. Born in Magnolia, Arkansas, he moved to Chicago at age 14, eventually joining the Chicago Blues scene, alongside Jimmy Reed, Freddie King, and Little Walter.

Providing a current assessment of Chicago music (in 1984), Living Blues magazine co-founder and editor Jim O’Neal, who is coming to this year’s Mississippi Book Festival, addressed the conference. At that time, Koko Taylor, Little Milton, and James Cotton ruled the roost. While Mississippi still influenced Chicago, O’Neal points out that it was now a two-way street of artistic inspiration.

As Evans suggests in the book’s contemporary conclusion, a lot has evolved within blues since 1984. Yet at the same time, different iterations and artists experience revivals on a cyclical basis, revealing the style’s long history. Point being, Charley Patton maintains as much relevance today as he did thirty and eighty years ago.

DeMatt Harkins of Jackson enjoys flipping pancakes and records with his wife and daughter.

Comments are closed.