Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (September 9)

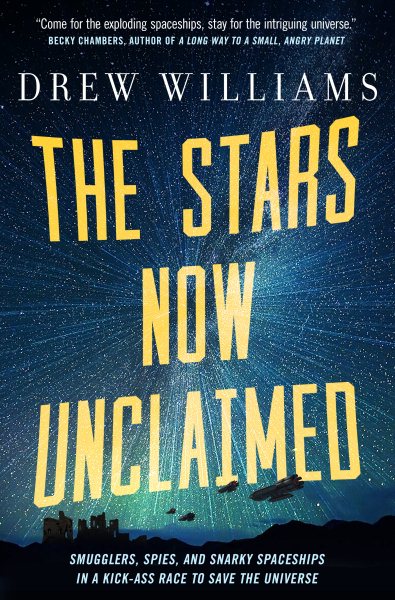

Although The Stars Now Unclaimed is his debut novel, Birmingham’s Drew Williams makes a distinction about his new sci-fi book: “It’s my first novel to be published,” he said. “It’s nowhere near my first novel to be written.”

Although The Stars Now Unclaimed is his debut novel, Birmingham’s Drew Williams makes a distinction about his new sci-fi book: “It’s my first novel to be published,” he said. “It’s nowhere near my first novel to be written.”

He explains why this difference matters, if only to himself.

“I remember hearing in a TED Talk a while back–and I’m not going to go look for it, so apologies to the speaker if I get this wrong–that it takes 10,000 hours of practice at anything before you can become truly ‘proficient’ at it; I’ve been chipping away at my 10,000 hours since I was a teenager, and believe me: readers can debate now whether I’ve reached ‘proficiency’ with The Stars Not Unclaimed,’ but the stuff I wrote back then was nowhere near it!”

Fortunately for Williams, The Stars Now Unclaimed is claiming a lot of attention among sci-fi and other readers–which works out well, as Stars is only the beginning of the series he has already planned for his newly minted characters.

Described as “a massive, galaxy-spanning tale of war, betrayal, friendship, and the kind commitment people make to a better future even at the cost of their own lives,” this future world is packed with strong characters, intense battles, and just enough trepidation to capture the attention of readers of all ages who love thrillers in any form.

The series is, as they say, another story–or actually, quite a few more stories. Boldly titled The Universe After, the collection will introduce its second volume A Chain Across the Dawn in May.

Tell me about yourself. The bio on the book flap is pretty bare bones–you got a job at a bookseller because you applied on a day when someone had just quit! You don’t like Moby-Dick. We want more! Tell us about Drew Williams.

Let’s see. I grew up right here in Birmingham–Birmingham, where we stare across the border at Atlanta and think “that could have been us, you know, if we’d really wanted it to be”–so I’ve been a native of the Deep South all my life; there’s just something about it, you know? Sure, the heat might be bad, and the humidity might be worse, and sure, in Birmingham specifically you have to reckon with a pretty terrible cultural legacy of institutional racism and basically being the villain in every story Yankees tell about the South, but there’s something about the people down here–just nicer, I think. More interested in what’s going on around them than wherever they think they’re supposed to be next.

Drew Williams

As far as my education goes, I left that part of the book flap because I didn’t want some kid to try and emulate it. The reason I needed that bookseller job was I’d dropped out of high school a few months before, so my education pretty much was the bookstore! Everything I know–and I don’t just mean about being a writer–I learned from books of history or psychology or from well-researched novels. It means I can hold forth exhaustively on a weirdly broad range of subjects–but there are also some really basic things that I can completely blank on.

I assume you have always been a science fiction fan. What sparked your interest in the genre? Who is your favorite sci-fi writer?

I literally do not remember seeing Star Wars for the first time; I do not remember–spoiler alert for, you know, a nearly 40-year-old film–ever watching The Empire Strikes Back and not knowing Darth Vader was Luke’s father.

The same goes for novels: I come from a family of, well, nerds, so both my father and mother read to my brother and me extensively when we were children, and they didn’t stop at kids’ books. One of my very first memories is my mother reading To Kill a Mockingbird to me–omitting some of the more graphic details of the nature of the central crime, most likely–whereas my father was more prone to just read to us whatever he had lying around at the time, whether that was Clive Cussler, Dave Duncan–look him up kids; a great many of his earlier works are out of print, but as far as I’m concerned he’s one of the preeminent fantasy authors of our time–or Arthur C. Clarke. Dune was the first “big deal” sci-fi novel I read myself, and I followed it up with a hopscotch path though Heinlein, David Feintuch–another unjustly overlooked sci-fi great–and even Kurt Vonnegut.

What prompted you to make the main character female? Did you find that to be more of a challenge?

That’s one of those things, honestly, that just happened: I sat down to write this novel, and there she was–I never had a single doubt in my mind that she was supposed to be anything other than female. I do think there’s something more interesting about the central relationship in the novel being more about a sort of pseudo-maternal connection than the parental one that might have arisen if I had made the lead male, that there’s a certain assumed vulnerability, a sense of not just protection but fostering of emotional growth that might not have been there otherwise, but honestly, that’s just me back-filling: I can’t claim to have don that on purpose.

As far as writing a female lead being a challenge goes: I think a great deal of how a person writes–consciously or otherwise–is defined by what we consume, in terms of narrative, whether that’s books, films, video games, whatever. And again, going back to my parents: I was never told to make a distinction as a child between “boy books” and “girl books”–I read both The Hardy Boys and Sweet Valley High. They were all just books, they were all just stories.

That’s a habit I’ve carried into adulthood–whether a book has a male lead or a female lead makes no difference whatsoever in my interest in the novel–and I think having read a great deal of literature with female leads makes it easier to write something with one.

Explain more about the “pulse” in The Stars Now Unclaimed, what it actually was, and how it chose which planets to send back in time.

Getting into some of those answers would be getting into spoiler territory for later books, but I’ll do my best!

Basically, the pulse in an unexplained cosmic event that swept through the universe about 100 years before the novel is set. With no apparent sense of purpose, it set about affecting almost every planet in the galaxy, affecting each on a slightly different scale.

So you might have one world where no technology more complex than steam-power can operate–a world stuck, permanently, in the Industrial Revolution–and another still fully capable of making spaceships and advanced artificial intelligence and jet-packs.

The reasons for that concept, honestly, were structural rather than metaphorical: I wanted a very broad canvas to play with, one where I could have wild spaceship battles in one scene, and forgotten, almost post-apocalyptic city-scapes to wander through in the next.

Your book includes a lot of battle scenes. Did you, like many others, find yourself intrigued with the action of the Star Wars space battles?

Star Wars is absolutely–no question, No. 1 with a bullet, full stop–the single most influential work of art in my life. I learned so much from those films, not just about narrative and storytelling, but in terms of who I am, and I think the appeal of Star Wars can be boiled down into a single concept that comes from Star Wars: even when things are wildly different, people are just people.

Those films have always succeeded in marrying eye-popping-ly beautiful imagery, alien and exotic and imaginative, with deep-seated human desires and conflicts.

I think the action sequences do the same thing. Yes, they might involve laser swords or giant walking tanks or an ancient monster that’s nothing more than a mouth buried in the sand, but they’re still about a man, trying to rescue a friend; about soldiers, trying to do their best to fight a desperate rear-guard action so their fight can go on; about a son, trying to find the man his father once was inside of the monster he’s become.

I very much tried to do the same thing in The Stars Now Unclaimed, to root the action, no matter how outlandish or insane, in who the character were.

Star Wars and other “space operas” seem to illustrate how good eventually overcomes evil. Is there a deeper meaning, or message, to your novel?

Two answers come to mind with that: the first is the theme of The Stars Now Unclaimed itself, which I think can be summarized with the concept that “even grief can be turned into good ends.” The second–which is slightly more germane to your question–is how I would summarize the theme of the entire series, which is “so long as parents try not to pass their won sins on to their children, the world can become a better place.” So long as we continually struggled to raise our children into people better than us–and to give them a world better than that which we inherited–there is no doubt in my mind that good will overcome evil, because evil is a thing that thrives where empathy has failed. Even if we don’t always succeed in that goal, it’s the trying that matters, I think.

Now that you are a published author, you’ll always be asked about what project you have coming out next. Can you tell us?

Book two, of course! I don’t think I can tell you much more than that, or my editor will skin my alive, but I will say characters are meant to grow, and change, otherwise there’s on point in writing a sequel.

Drew Williams will be at Lemuria today on Monday, September 10, at 5:00 to sign and read from The Stars Now Unclaimed.

Comments are closed.