Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 1)

For Mississippi native T.R. Hummer, 2018 is turning out to be a year of life and death–and beyond–speaking in literary terms.

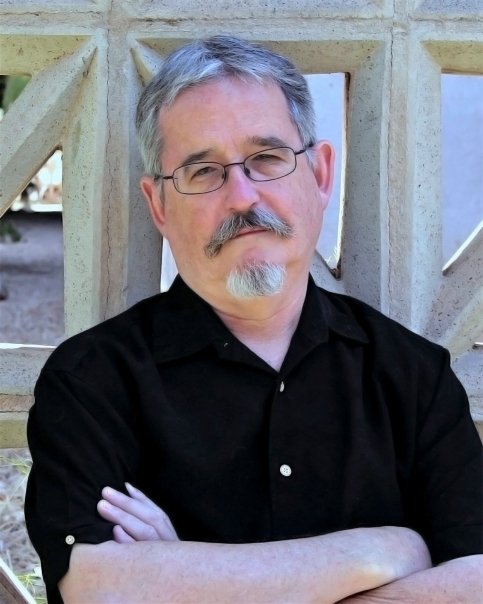

The poet, editor and essayist who grew up on a farm near Macon now has 14 books of poetry and essays to his credit–two of which he added just this year and that challenge the reader to consider, on a deeper level, what happens at death and afterward.

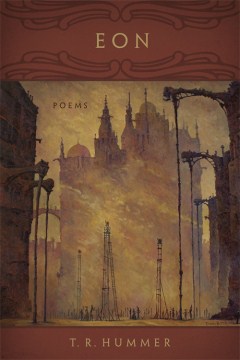

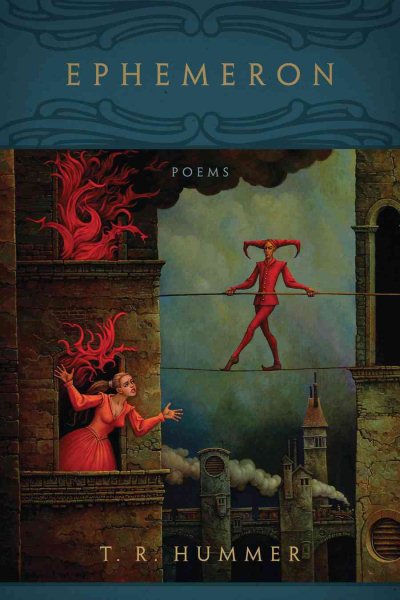

Hummer’s 2018 release are Eon (the third volume in his LSU Press trilogy that includes Ephemeron, 2012, and Skandalon 2014); and After the Afterlife (Acre Books), which carries his trilogy on birth, life, and death to the next “logical” step: examining what consciousness comes even after one’s demise.

Hummer’s 2018 release are Eon (the third volume in his LSU Press trilogy that includes Ephemeron, 2012, and Skandalon 2014); and After the Afterlife (Acre Books), which carries his trilogy on birth, life, and death to the next “logical” step: examining what consciousness comes even after one’s demise.

His honors include a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship in poetry, a National Endowment for the Arts Individual Artist Grant in Poetry, the Richard Wright Award for Artistic Excellence, the Hanes Poetry Prize, and the Donald Justice Award in Poetry.

Hiw work has also been published in The New Yorker, Harper’s, Atlantic Monthly, The Literati Review, Paris Review, and Georgia Review.

Hummer holds undergraduate and master’s degrees from the University of Southern Mississippi; and a doctorate degree from the University of Utah.

He has also enjoyed a long career teaching poetry and creative writing at several colleges and universities throughout the country, most recently at Arizona State University.

Hummer’s lengthy involvement with literary publishing includes serving as editor of Quarterly West magazine at the University of Utah; then poetry editor of Cimarron Review at Oklahoma State University; editor-in-chief of The Kenyon Review, later of the New England Review, and then The Georgia Review.

He now lives in Cold Spring, New York, and is married to the writer Elizabeth Cody Kimmel, about whom he advises: “Look her up; her track record is very impressive.”

Please tell me about your new release Eon–a study of death, the eternal, and what lies beyond. Why this topic, and why now? How does Eon fit into the context of the trilogy that includes Ephemeron and Skandalon.

T.R. (Terry) Hummer

Well, the eternal is always timely, don’t you think? Eon, though it works just as fine as a stand-alone volume, is as you say part of a trilogy of poetry volumes written over eight years or so.

The originating impulse was the birth of my child in 2002–the turn of the millennium, and also the year in which I was 50. The arrival of that child –my second; my first was born in 1977, so there is rather a large gap between my kids, which has interesting effects on such matters as sibling rivalry–had enormous emotional repercussions for me, which I expected going in.

I fell in love with her before she was born, as one will, but as soon as she was in the world, I also felt–to my surprise–that her arrival revealed to me more than anything else ever had the certainty of my own mortality. The title poem of the first volume is about that, and the whole trilogy unfolds from there.

So, it’s a natural part of the progression for the last volume–culminating when I was 60–should take on mortality head-on. Insofar as that is possible.

The cover of the book is a stunning work of imagery by German surreal artist Michael Hutter. How does the scene of this work fit with the poetry in Eon?

All three volumes in the trilogy have cover art by Michael Hutter–partly to provide visual unity among the three, but also because there is something about his work that, to my mind at least, suits the poetry perfectly. His painting is timeless, and yet it continually alludes to, and plays games with, tradition, both in terms of technique and of subject. It’s often very witty also–certainly the cover of Ephemeron has that quality, and of Skandalon also, through in a more muted way. The cover of Eon is the most somber of the three–appropriately, given the subject.

All three volumes in the trilogy have cover art by Michael Hutter–partly to provide visual unity among the three, but also because there is something about his work that, to my mind at least, suits the poetry perfectly. His painting is timeless, and yet it continually alludes to, and plays games with, tradition, both in terms of technique and of subject. It’s often very witty also–certainly the cover of Ephemeron has that quality, and of Skandalon also, through in a more muted way. The cover of Eon is the most somber of the three–appropriately, given the subject.

I’ve read that you are a jazz buff, a blues fan, and a saxophonist. With its distinctive rhythm and tempo, do you think your music style has rubbed off onto your writing style?

This a very complicated question. The relationship between music and language is vital, and mysterious. I have spent decades trying to unpack it, and really have no even scratched the surface. However, I can say two things briefly: first, that I found music a long time before I found poetry, but that the one led me to the other; and second, that the example of many musicians whose work I admired and admire taught me how to be an artist.

Growing up in the small town of Macon, in what ways would you say your Mississippi heritage influenced your writing?

Actually, I didn’t grow up in Macon. We were 15 miles outside Macon, and in those days 15 miles was a very long way. I grew up on a farm in a very remote part of the state–far more remote in the 1950s when I was a child than now.

On the one hand, I grew up among animals and plants and all the elemental things one encounters and learns about on a farm–especially on the kind of farm that was then, not a mono-crop agribusiness outlet, but a diverse subsistence farm that was an ecosystem and, in a sense, a society. The farm turned, in the 60s, to a different model and became a different place, but I was already leaving by then. So, I received that kind of education from the people and from the creatures who surrounded me. At the same time, I grew up in Mississippi in the 50s and 60s: the bad old days of Jim Crow and the arrival full-bore of the civil rights movement. It was a quiet rural life, but we also lived in a war zone. Everything was changing, and it had to change. Everything about our old life for good reason was dying and it had to die.

None of that is easy for a young person to digest, but there it was. There is an enormous amount more to say on the subject, too much for this format. I will leave it at this: growing up white in the Jim Crow South had consequences. Growing up black there had worse ones. I have spent decades trying to sort these matters out in my own mind, and being a poet is part of the process.

You have another new book out this year: After the Afterlife, from Acre Books. Why two in one year?

It’s really an accident of publishers’ schedules. Eon was finished several years ago, but took a long time to see print. The work in After the Afterlife is newer, but Acre Books worked faster, so here they both are.

The title After the Afterlife suggests a connection, a continuity, with Eon. Is that the case?

Definitely. The newer work is different, of course, partly because After the Afterlife arrives as sort of liberation from the labor of writing a trilogy. But it all comes from one mind, and I only have two and a half ideas total, so of course it’s connected.

During your years as a professor, if there a defining lesson or message about writing poetry that you have tried to instill in your students?

I retired a couple of years ago, so my relationship with the classroom has changed, but it hasn’t vanished. The one thing I always wanted students to understand about writing–and this is true of any kind of writing, not only the writing of poetry–is that it is always all about consciousness. No matter what the overt subject of style of a poem, its subject is consciousness, and its material is consciousness. A writer creates a score for consciousness, the way a composer creates a score for orchestra or jazz band. The reader’s job is to play the instrument of consciousness in response. Reading and writing obviously are complementary in that way, and both the writer and the readers have to be, dare I say, conscious of that fact.

T.R. Hummer will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival Aug. 18 as a participant in the “Waxing Poetic with the Pros” poetry panel at 9:30 a.m. in the State Capitol Room 201 A.

Comments are closed.