Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 4)

Jonathan Miles

A former Oxford resident and author of two acclaimed novels, Jonathan Miles returns with his latest tale, Anatomy of a Miracle, an ambitious story of an Army veteran who comes back to his hometown of Biloxi a paraplegic–until his world is turned upside down one day when he inexplicably stands up from his wheelchair and walks.

An Ohio native who wound up in Oxford as a teenager, Miles began his career as a journalist for the Oxford Eagle newspaper and later became a columnist for the New York Times. His novels include Dear American Airlines and Want Not, and he also authored a book on fish and game cooking, The Wild Chef.

Miels said he “spent years living in a tiny cabin in the woods near Abbeville until I married a Coast girl–she’s a Ladner, so the Coastiest of Coast girls–and got civilized.”

He and his family now live in rural New Jersey, “a little up from Princeton,” he said, adding, “my wife and children spend much of the summers in Mississippi, and this seems to have immunized my kids from acquiring New Jersey accents.”

Tell me what brought you to live in Oxford in the first place, and when.

Short answer: blues, 1989. The longer one: I came to Oxford as a blues-obsessed 18-year-old, having stumbled upon Living Blues magazine in a record shop and noting it was published by Ole Miss.

But after a few years of guitars and harmonicas another stumble happened: I wandered into a writing class (at the University of Mississippi) taught by Barry Hannah and frankly got my ears blown back. Barry resurrected a childhood ambition to write, and soon after, Larry Brown took me under his wing and kept me there until his death. At the time, I didn’t realize I was getting an education from Larry, because most of the time we were laughing and cutting up, but in retrospect I’d put all those years spent riding backroads and talking books and writing up against any Ivy League MFA program.

One of the things I’m most proud of in life is that Larry’s daughter Leanne named a son Larry Miles. That little boy has no choice but to become a novelist.

Anatomy of a Miracle tells the story of a paralyzed Biloxi Army veteran’s miraculous recovery, and the many ways this event changes his life forever. What inspired the story?

It began with a simple what-if question: What if a miraculous-seeming event happened today, in America? An event that defied all explanation? What would it look like–in the press, on social media? What kinds of cultural fault lines would it cause to rumble? And what effects–aside from the physical recovery–would this event have on the lives of those it touched? It was a spiral of questions.

It began with a simple what-if question: What if a miraculous-seeming event happened today, in America? An event that defied all explanation? What would it look like–in the press, on social media? What kinds of cultural fault lines would it cause to rumble? And what effects–aside from the physical recovery–would this event have on the lives of those it touched? It was a spiral of questions.

Main character Cameron Harris’s story of healing spawns many side plots, including the tireless pursuit of his doctor to find out how this could be medically possible; the effect his healing has on the convenience store at whose front sidewalk Cameron realizes he can suddenly rise from his wheelchair and walk; a Vatican investigation of whether this event qualifies as a miracle; and the back story on what really happened in Afghanistan that left him paralyzed. Was it difficult working with so many characters and subplots?

I wanted to depict the effects of Cameron’s recovery as broadly as possible–to map the reverberations as they went shaking through the local community, the country, and in some ways, the world. In real life, I knew, Cameron’s story would be claimed by many different people, tweaking and twisting it to fit their own desires and worldviews, and part of Cameron’s struggle in the novel is to reclaim that story–with all its complexities–for himself.

As for any difficulty with writing it that way: very little, to be honest, I felt like I had this buffet of intriguing characters, from the convenience store owners to the Roman investigator to the VA physician who’s the uneasy daughter of a fabulizing Delta novelist. I just grazed on this buffet of characters and storylines.

Cameron’s sister Tonya is a strong force in his life, after his parents died and he suffered life-changing injuries in Afghanistan. She’s an interesting character who regularly adds humor to the story. Please tell me about her.

Tayna Harris is, to my way of thinking, one of the strongest people in the book. When Cameron recovers, it’s after four years in her care; and you could argue that, because of the way she parented him after their father abandoned them and their mother died, she’s really been his lifelong caretaker. Aside from jobs at Dollar General and Waffle House, taking care of her little brother has been her primary occupation–which means that Cameron’s recovery upturns her life just as radically as it upturns his. But she deals with life differently than Cameron does. He mulls. She cracks jokes. She meets life’s absurdities on their level.

A question that runs throughout the story is Cameron’s longing to know why such an extraordinary miracle happened to him. It’s interesting that Cameron’s healing changes his life to such an extent that he finally confesses to his sister that he doesn’t know who he is anymore. In what ways did he find that to be true?

For Cameron, the mystery of his physical recovery is compounded by the mystery of why it happened to him. He didn’t explicitly ask for it, through prayer or other means; he didn’t strive toward it by taking care of his own physical and mental well-being–for instance, he filled most days with beer drinking and video games–and, deep down, he doesn’t even think he deserved it.

What his recovery ultimately forces is a very hard look in the mirror, provoked in part by so many other people digging into his life to determine for themselves why Cameron was on the receiving end of a possible miracle. Cameron is a mystery to them as well as to himself, and part of his quest to understands his recovery is finally coming to grips with who he is.

The fact that Cameron and his sister Tanya were offered–and accepted–an opportunity to star in a reality show, Miracle Man, about their lives since Cameron’s healing, was an interesting subplot, but his feelings about that project seemed to change quickly after he heard of the shooting death of his neighbor’s grandson. How did that alter his attitude about that show?

It struck me early on that, in the wake of press attention to the recovery, of course reality-television would come calling. In our current media climate, that’s as certain as the sun rising. Reality-television is also, of course, not anything like reality; it’s as scripted as a novel.

Cameron is willing to go along with the lie until seeing himself through his neighbor’s eyes in the wake of a pointless tragedy, and viewing his senseless fortune as the flip side to that senseless misfortune. As well, Cameron buckles under the responsibilities of his new life at that moment: the neighbor had asked him to pray for her grandson, and he’d let her down. He realizes he can no longer stand being a vessel for faith, either onscreen or off. It breaks him, and ultimately causes all hell to snap loose.

Anatomy of a Miracle is your third book. Do you have other projects on the horizon?

This was my first fiction set in Mississippi, after one novel set in New York and the other set in a terminal at Chicago O’Hare airport. There’s another novel in the works, and the characters have already landed in Mississippi for a while–this time the 1930s Delta.

Sometimes being a novelist is like being a travel agent. You book travel for your characters with promises of a time they won’t forget. Though being a novelist is better because you get to come along with them.

Jonathan Miles will be at Lemuria on Tuesday, March 20, to sign and read from Anatomy of a Miracle. This book was chosen as one of our two March 2018 selections for Lemuria’s First Editions Club for Fiction.

The Fighter opens with a harrowing scene of high-speed DUI and pretty much never lets up from there. It’s the tale of a washed-up, alcohol- and pill-addicted cage fighter prepping for what will be his very last fight—either for good or ill. The stakes are life-or-death—no quarter asked or given. It is a brutal subculture of the South we know, but a fascinating one.

The Fighter opens with a harrowing scene of high-speed DUI and pretty much never lets up from there. It’s the tale of a washed-up, alcohol- and pill-addicted cage fighter prepping for what will be his very last fight—either for good or ill. The stakes are life-or-death—no quarter asked or given. It is a brutal subculture of the South we know, but a fascinating one. Newlyweds Celestial and Roy drive from their home in Atlanta to visit Roy’s parents in Eloe, Louisiana. Tension between Celestial and her mother-in-law makes the young couple decide to rent a hotel room rather than stay at the house. At the hotel, an argument between the couple sends Roy out of their room for less than an hour, an hour that will determine the course of both of their lives.

Newlyweds Celestial and Roy drive from their home in Atlanta to visit Roy’s parents in Eloe, Louisiana. Tension between Celestial and her mother-in-law makes the young couple decide to rent a hotel room rather than stay at the house. At the hotel, an argument between the couple sends Roy out of their room for less than an hour, an hour that will determine the course of both of their lives.

Jamie Quatro’s debut novel,

Jamie Quatro’s debut novel,

You’ve enjoyed a full life — world traveler, family man, would-be farm hand and at times you’ve turned your attention to politics (mostly through your deep interest in policy), journalism, the military, and your own formal education, not to mention an amazing career as a writer. How have you managed to fit so many interests into your seven decades?

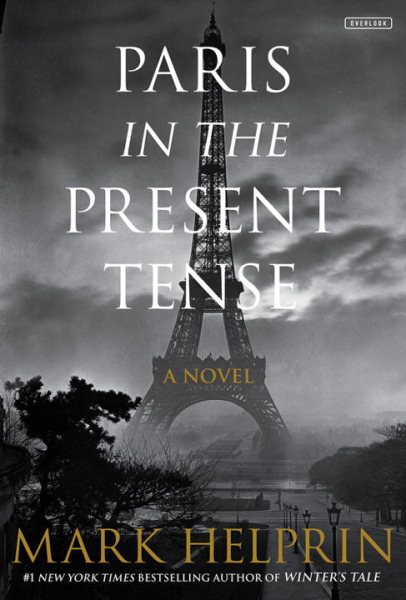

You’ve enjoyed a full life — world traveler, family man, would-be farm hand and at times you’ve turned your attention to politics (mostly through your deep interest in policy), journalism, the military, and your own formal education, not to mention an amazing career as a writer. How have you managed to fit so many interests into your seven decades? Your newest book, “Paris in the Present Tense,” is another fictional work presented on a grand scale. In this story of an aging man consumed with worry about his grandson’s serious illness, main character Jules Lacour is keenly aware of his own inability to offer much in the way of financial support. A deep thinker with strong convictions, he looks back on his own life with his share of regrets and fears. In many ways, most of us have a lot in common with Lacour. Can you share your reflections on him?

Your newest book, “Paris in the Present Tense,” is another fictional work presented on a grand scale. In this story of an aging man consumed with worry about his grandson’s serious illness, main character Jules Lacour is keenly aware of his own inability to offer much in the way of financial support. A deep thinker with strong convictions, he looks back on his own life with his share of regrets and fears. In many ways, most of us have a lot in common with Lacour. Can you share your reflections on him?