Interview with George Saunders by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger.

Long a master of uniquely inspired short stories, George Saunders’ career as a novelist has just come to life with the release of his long-awaited debut novel. The entire tale unfolds over the course of one night — and almost entirely in a surreal graveyard.

Long a master of uniquely inspired short stories, George Saunders’ career as a novelist has just come to life with the release of his long-awaited debut novel. The entire tale unfolds over the course of one night — and almost entirely in a surreal graveyard.

Lincoln in the Bardo, in Saunders’ trademark over-the-top imaginative style, recounts the story of the death of the 11-year-old son of President Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary. While based on historic fact, Saunders takes literary license after the newly deceased Willie Lincoln finds himself in a form of purgatory, as the fate of his soul plays out among a host of opinionated ghosts with no qualms about sharing their take on the boy’s destiny.

The author of nine books, including Tenth of December (a finalist for the National Book Award), Saunders also won the inaugural Folio Prize for the best work of fiction in English and the Story Prize for Best Short Story Collection. He has received MacArthur and Guggenheim Fellowships, the PEN/Malamud Prize for excellence in the short story, and was recently elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In 2013, Saunders was named one of the world’s 100 most influential people by Time magazine. He now teaches in the Creative Writing Program at his alma mater, Syracuse University.

Lincoln in the Bardo begins with the true story of the death of Abraham and Mary Lincoln’s son at the height of the Civil War—but it takes a wildly unexpected (and fictional) turn. How did you come up with this surprising scenario of historical fact and fiction for this story?

Honestly, trial-and-error. I knew, at the outset, how I didn’t want to tell it: in a sort of standard, third-person realist voice—and I knew this because I’d tried it—ugh! I am always trying to steer toward the fun, or what feels truthful and uncommon. So, all of the book’s odd elements came out of that desire.

Honestly, trial-and-error. I knew, at the outset, how I didn’t want to tell it: in a sort of standard, third-person realist voice—and I knew this because I’d tried it—ugh! I am always trying to steer toward the fun, or what feels truthful and uncommon. So, all of the book’s odd elements came out of that desire.

For example, I didn’t want to have to say, you know, “Suddenly, a GHOST glided in from the west.” Because then the reader has this white-sheeted, Central Casting ghost in mind, instead of the complex, sad beings I had in mind. So that leads to the device of having the ghosts only be “present” in monologue form, or as described by another ghost, in passing. And so on. Basically: try something out and if it feels lame, familiar, predictable, deny yourself that approach. Rinse, lather, repeat.

This book is your first novel, after years of remarkable success writing short stories. What inspired you to change gears?

Really, it was just responding to the demands of the story. I think every story has a sort of innate DNA, and this one just wanted to be…longer. I fought it, believe me—tried to make it as efficient as I could. But in the end it had this sort of proud insistence, like, “Sir, believe me: I know how long I need to be.”

You say in your own biographical info that you “barely” graduated from the Colorado School of Mines, and after years of working as a geophysicist, you went on to hold day jobs as a doorman, roofer, convenience store clerk, and even a slaughterhouse worker, before you landed in the MFA program at Syracuse University. How old were you when you began writing, and how did your rich vocational and educational experiences influence your writing?

I started really writing at about 25, I think, just after that roofing job. I’d been dabbling before, but at that point some friends offered me their attic for two months, so I could give it a real try. Which I did—with crummy results, but it was the first time I’d ever treated it as a job—something you had to do every day. And it was the first time I ran into legit artistic problems—finished stories, didn’t like them. That revulsion at your own work is a great artistic blessing, because it indicates that you have… taste. So I see that period as the beginning of a serious writing practice.

As far as the jobs and all of that—now, I understand that period as being sort of like America 101—a chance to see what our country—and capitalism—are really like, face-to-face. It was invaluable in giving me a little confidence that what I felt might be more generally true. In geology, we had to spend a summer working in the field, to solidify the more theoretical aspects of what we’d learned. This “hard-knock” period in my working life was like that: a chance to test “beliefs” versus “the real.” And I think it gave me a fundamental fondness and sympathy for working-class life and people.

Put simply, your writing is not like anyone else’s. Your short stories are a sort of highly creative mix of Dr. Seuss, folk tales and satire—with a large dose of humor. Lincoln in the Bardo is even harder to describe, but “original” and “inventive” come to mind. How do you explain your full-tilt imagination?

Thank you! That would be my number one goal; I don’t mind being a little “off” as long as it feels like only I could have come up with that particular flavor of offness. For me, “imagination” is more accurately described as “artistic patience.” I do have an odd mind—that, I’ve finally come to believe. But revision is what takes the products of an odd mind and makes them understandable and orderly to other people. For me, that only happens with many, many passes through a story. You are essentially giving the text many opportunities to speak originally to you—which might, to a reader, feel, in the end, like, “Oh, that writer is unique.” But at least part of what is unique is the willingness to abide with a story for a ridiculously long time. Like a miner squatting in the river for a year without standing up, or giving up hope. Or showering. Or going on a date.

The story takes place over the course of one night, after Willie is buried—and he has quite a revelation for the “spirits” that visit him in his new state of being: they are all dead! Please explain how that “surprise” affects their perspective—and what your message here means to us all.

Well, the ghosts exist in a state of willed denial. They either genuinely don’t realize they’re dead, or maybe do, a little, and are constantly trying to push this knowledge away from themselves, so they can “stay.” Willie is young and honest and when he realizes his state, he can’t help but blurt it out. To me, there was a parallel here—the dead don’t know they’re dead and we don’t know certain key things about ourselves—that we are going to die, for one; but also, we go around believing that we are permanent and central. So just as a ghost might undergo a sort of spiritual awakening as he realizes he’s dead and thereby progress to the next level, we might undergo a spiritual awakening and, in a sense, realize we are alive: temporary, vulnerable, actually joined with all other beings and not separate from them at all.

Your ability to create unexpected characters is a hallmark of your work. In fact, the characters in a number of your short stories are not even human—they are sometimes animals, and sometimes “not exactly humans.” What do they represent to readers?

A character is really a form of what we might call activated rhetoric—it is useful for something, as we construct the “argument” that is a story. So whether that character is a person or a ghost or a talking fox, it exists as a way for the writer to flesh out the logical argument the story is making. I’ll sometimes choose a non-human character because it’s the best way to give voice to that which I need in the story. So, an early story called “The Wavemaker Falters” was from the point of view of a guy who’d accidentally killed a kid. I needed some way to represent his guilt that it wasn’t just him talking about it. So the artistic eye sort of goes roving around and thinks, “Who best to represent that viewpoint?” It could be his mother or father, who does actually make an appearance, later—but when that eye falls upon the kid himself, in ghostly form, it just seems … cool. Odd. And then you get to let that kid speak. And the reader, I think, feels that as both new-ish and emotionally direct: the shortest line between two points.

Humor is a consistent theme in your work, which, at the same time, addresses elements that are dark, and serious, and frightening. How do you explain your knack for that effortless blending?

My childhood. Our family was very funny and, well … a little dark. Sarcastic. We got a lot of fun out of ironic joking but also had so much genuine feeling. The “funny” was the way we expressed the “feeling”—teasing, joking, doing voices were the most authentic emotion-conveying modes for us, somehow.

It must be a great source of pride to be teaching at your alma mater, Syracuse. What’s it like to be training a new generation of writers?

It is the best. We get around 600 to 650 applications a year and choose six of those to come. So they are already amazing and we get to enjoy three years of proximity to these bright young minds. It keeps a person honest, and freshly reminds the teacher that talent is eternal—it’s there in every generation, albeit in a slightly era-specialized form.

Can readers expect more novels from you now?

I honestly don’t know—it’s the first time in many years that I have a mostly empty desk. While getting this book ready, I’ve been working on a TV version of my story “Sea Oak.” I plan to get home from the tour for the “Lincoln” book and spend a lot of days just farting around, to see what wants to be next.

Lincoln in the Bardo is the March 2017 selection for the Lemuria First Editions Club. George Saunders will appear for a signing and reading at 5 p.m. Thursday, February 23, at the Gertrude C. Ford Academic Complex, Room 215, Millsaps College in Jackson.

The 31 pieces included in Mary Gaitskill’s new book, Somebody with a Little Hammer, were written over two decades, many of them originally book reviews. That normally makes for a very poor collection. Miscellanies can read as miscellaneous, scattershot assignments written for various editors in various magazine styles, as opposed to having been conceived of and executed through an author’s passion. Such collections often have no centrifugal force binding them. Further, such collections often smell a little past-their-sell-by-date; 20-year-old reviews might disparage books rightly forgotten, or heap early praise on books so heaped with post-publication prizes that the reviewer’s stance fails to enlighten. The earnest charge–“Rush out and buy this book!”–loses force when the book’s 10 years out of print.

The 31 pieces included in Mary Gaitskill’s new book, Somebody with a Little Hammer, were written over two decades, many of them originally book reviews. That normally makes for a very poor collection. Miscellanies can read as miscellaneous, scattershot assignments written for various editors in various magazine styles, as opposed to having been conceived of and executed through an author’s passion. Such collections often have no centrifugal force binding them. Further, such collections often smell a little past-their-sell-by-date; 20-year-old reviews might disparage books rightly forgotten, or heap early praise on books so heaped with post-publication prizes that the reviewer’s stance fails to enlighten. The earnest charge–“Rush out and buy this book!”–loses force when the book’s 10 years out of print.

Celine specializes in bringing families back together, for example, finding parents that had to give their children up for adoption. She has no interest in looking for cheating spouses or catching white collar criminals. Is it weird to say that I want to be like Celine when I grow up? Not that I want to be a private detective (just kidding, I totally do), but I want to be as calm and collected as she is. Her husband, Pete, is a man of few words and just as smart as Celine. He often accompanies Celine on her cases, and offers great insight on them.

Celine specializes in bringing families back together, for example, finding parents that had to give their children up for adoption. She has no interest in looking for cheating spouses or catching white collar criminals. Is it weird to say that I want to be like Celine when I grow up? Not that I want to be a private detective (just kidding, I totally do), but I want to be as calm and collected as she is. Her husband, Pete, is a man of few words and just as smart as Celine. He often accompanies Celine on her cases, and offers great insight on them. Linda is a fourteen-year-old girl who has a perplexing home life with her parents. They live in an abandoned cabin that used to be part of an old commune community in Northern Minnesota. She attends school, where she is an outsider. Her peers tend to either ignore her or make fun of her for being such a peculiar individual, often calling her a “freak”.

Linda is a fourteen-year-old girl who has a perplexing home life with her parents. They live in an abandoned cabin that used to be part of an old commune community in Northern Minnesota. She attends school, where she is an outsider. Her peers tend to either ignore her or make fun of her for being such a peculiar individual, often calling her a “freak”. We soon find out that the teacher has a past dealing with child pornography and Lily has accused him of behaving inappropriately with her. The implications of the teacher’s arrest deeply affect Linda and her perspective on human relationships. She retreats to her home and works with the family dogs during the summer months.

We soon find out that the teacher has a past dealing with child pornography and Lily has accused him of behaving inappropriately with her. The implications of the teacher’s arrest deeply affect Linda and her perspective on human relationships. She retreats to her home and works with the family dogs during the summer months. It’s so easy to take our freedom of speech for granted. In

It’s so easy to take our freedom of speech for granted. In  The way Towles writes his descriptions is playful and witty. The Count himself is the charming gentleman we’d like to imagine the aristocracy to be. There’s often little asides in the book that explain certain things in further detail, one of my favorites being a footnote that spans almost two pages. In one spot, Towles tells us to forget about a character, but to be on the lookout for another character that’s going to make a brief appearance in the next chapter. Occasionally Towles will go ahead and tell the reader what’s going to happen even further down the timeline.

The way Towles writes his descriptions is playful and witty. The Count himself is the charming gentleman we’d like to imagine the aristocracy to be. There’s often little asides in the book that explain certain things in further detail, one of my favorites being a footnote that spans almost two pages. In one spot, Towles tells us to forget about a character, but to be on the lookout for another character that’s going to make a brief appearance in the next chapter. Occasionally Towles will go ahead and tell the reader what’s going to happen even further down the timeline.

Long a master of uniquely inspired short stories, George Saunders’ career as a novelist has just come to life with the release of his long-awaited debut novel. The entire tale unfolds over the course of one night — and almost entirely in a surreal graveyard.

Long a master of uniquely inspired short stories, George Saunders’ career as a novelist has just come to life with the release of his long-awaited debut novel. The entire tale unfolds over the course of one night — and almost entirely in a surreal graveyard. Honestly, trial-and-error. I knew, at the outset, how I didn’t want to tell it: in a sort of standard, third-person realist voice—and I knew this because I’d tried it—ugh! I am always trying to steer toward the fun, or what feels truthful and uncommon. So, all of the book’s odd elements came out of that desire.

Honestly, trial-and-error. I knew, at the outset, how I didn’t want to tell it: in a sort of standard, third-person realist voice—and I knew this because I’d tried it—ugh! I am always trying to steer toward the fun, or what feels truthful and uncommon. So, all of the book’s odd elements came out of that desire. Every once in a while, a book comes along that is so simple, rich, textured and real that you know some invisible line has been crossed, that something new has been created that will live on to become a classic.

Every once in a while, a book comes along that is so simple, rich, textured and real that you know some invisible line has been crossed, that something new has been created that will live on to become a classic.

With

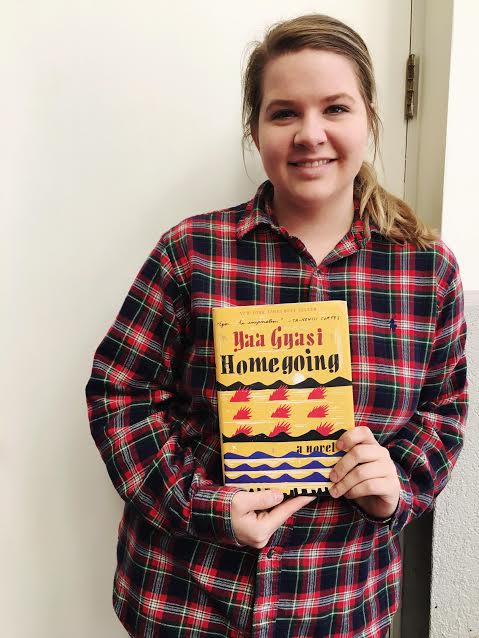

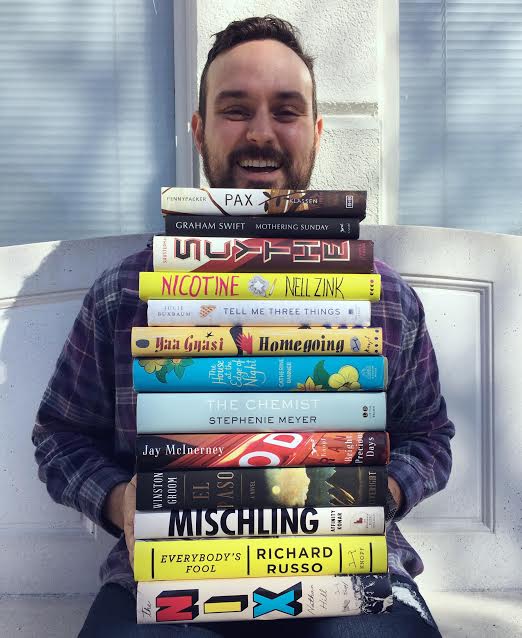

With  “Homegoing is about the families of two sisters, one of whom marries a slaver, and one who is taken into slavery. It is a story that spans generations that is for every generation. You’ll fall in love with every character. Gyasi weaves together a compelling and beautiful tale. ” – Abbie

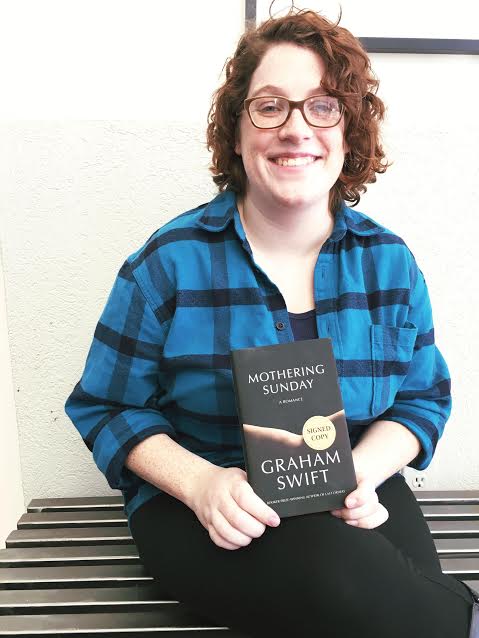

“Homegoing is about the families of two sisters, one of whom marries a slaver, and one who is taken into slavery. It is a story that spans generations that is for every generation. You’ll fall in love with every character. Gyasi weaves together a compelling and beautiful tale. ” – Abbie Mothering Sunday is a short and fabulous book about

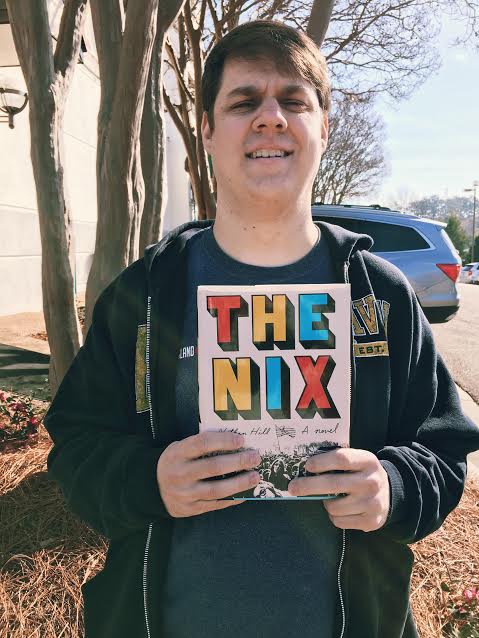

Mothering Sunday is a short and fabulous book about The Nix is a spectacular debut novel about a writer searching for the truth about the mother who abandoned him, only to make headline news decades later. The tone alternates between comic and serious, and and it expertly captures the zeitgeist of both the 2010s and the 1960s. Hill does such a good job writing from multiple perspetives. – Andrew

The Nix is a spectacular debut novel about a writer searching for the truth about the mother who abandoned him, only to make headline news decades later. The tone alternates between comic and serious, and and it expertly captures the zeitgeist of both the 2010s and the 1960s. Hill does such a good job writing from multiple perspetives. – Andrew

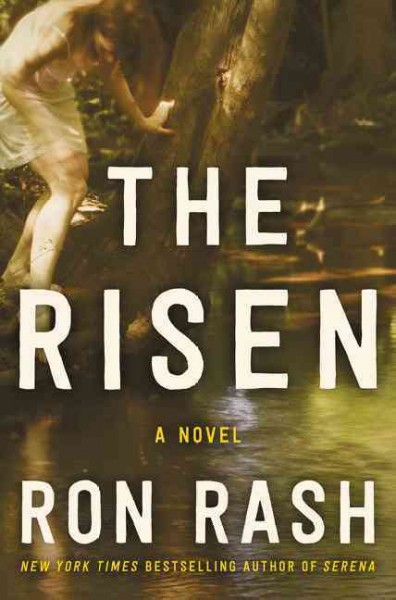

Like all of Rash’s fiction, The Risen is set in North Carolina, and this place informs both the characters and plot. Our narrator, Eugene, tells us two parallel stories: first, he recalls his youth, specifically the

Like all of Rash’s fiction, The Risen is set in North Carolina, and this place informs both the characters and plot. Our narrator, Eugene, tells us two parallel stories: first, he recalls his youth, specifically the