By Jim Ewing. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (May 12)

One of the enduring mysteries after the 2016 death of author Harper Lee was: Did she work on a book to follow her iconic To Kill a Mockingbird and was there an unpublished manuscript?

Casey Cep in Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee does an admirable job in solving the mystery—in more ways that one.

Casey Cep in Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee does an admirable job in solving the mystery—in more ways that one.

Foremost, she solves the mystery of the much rumored book that Lee was reportedly working on through painstaking journalism, tracking down sources, doing interviews, resurrecting lost notes and compiling a fascinating picture of Lee’s life post-Mockingbird.

But she also resurrects the tale itself, the story that Lee referred to as “The Reverend,” producing a book within a book by writing herself the book that Lee couldn’t find a way to piece together.

Cep recounts that Lee spent three years trying to write “The Reverend,” going about it the same way that she had helped childhood friend Truman Capote compile his book In Cold Blood.

Just as Lee and Capote spent months in Kansas doing interviews and watching the murder trial that resulted in the “nonfiction novel” Capote wrote to great acclaim, Cep writes, Lee attempted to recreate the feat alone in Alexander City, Ala.

Lee’s case of suspicious deaths revolved around the Rev. Willie Maxwell, beginning with his wife Mary Lou found dead in her car Aug. 3, 1970. While investigators couldn’t prove a murder, they found that “his private life bore little resemblance to the one his parishioners thought he was living, and no resemblance at all to those he extolled in his sermons.”

He was acquitted at trial, based on the possibly perjured testimony of his neighbour, Dorcas Anderson, whom 15 months after the death, he married.

She was 27 to his 46 and, conveniently, and suspiciously also, a new widow.

It was a trend. Then, his brother died and, like Mary Lou before him, Maxwell had taken out several life insurance policies on him, totaling $100,000 (about $500,000 today).

On Sept. 20, 1972, Dorcas was found dead—with 17 life insurance policies the Reverend had on her.

He married wife number three in November, 1974, with Ophelia Burns. Shortly after, a nephew died.

All were under suspicious circumstances that neither police nor insurance investigators could prove were the product of a crime.

The community began to view the black preacher as a hoodoo conjurer. After his first wife’s death, “a lot of people were convinced that he had used voodoo to fix the jury … and charm a younger woman” into marrying him, but “as time passed and more people died, the stories about the reverend grew stronger, stranger, and, if possible, more sinister.”

It was said “he hung white chickens upside down from the pecan trees outside his house to keep away unwanted spirits and painted blood on his doorsteps to keep away the authorities. … Drive by his front door, and the headlights on any car would go dark. Say a cross word against him, and he would lay a trick on you.”

One could certainly see how this Southern gothic tale would be enticing for the creator of such characters as Scout, Atticus—and the scary Boo Radley.

But Cep posits that in “The Reverend” Lee believed she would redeem herself as a story teller of the “true” South—where the status of race relations was more complex and nuanced than black and white, as in the morality tale of Mockingbird.

“Mockingbird had been read as a clarion call for civil rights, but Lee’s views were more complicated than any editor wanted to put into print,” Cep writes, as demonstrated by Go Set a Watchman, the original text for Mockingbird.

When Maxwell was brought to trial a final time, in 1977, with the suspicious death of Maxwell’s adopted daughter, Lee was there to watch it, and she found the medium for writing a book that would parallel Mockingbird, but present it in a more complex manner.

It had a black hero, who was also a vigilante operating outside the law; a black villain, who while masquerading as a preacher was also believed to be evil incarnate; a white crusading attorney, who was also profiting off of black death; crimes that looked like murder but were treated more like fraud, and “white and black lives that existed almost side by side in small Southern towns but were worlds apart.”

How and why “The Reverend” never came to print is a separate story, believably related.

In Furious, Lee’s admirers will discover a new perspective on the reclusive author while also catching an enticing glimpse of the “lost” book that could or would have been a more modern sequel of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Casey Cep will be at Lemuria on Monday, May 13, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee. Lemuria has selected Furious Hours as its May 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

In a fast-paced page-turner, Philip Shirley weaves a tale of intrigue and nation-jumping that renews the debate over Elvis in the mystery novel

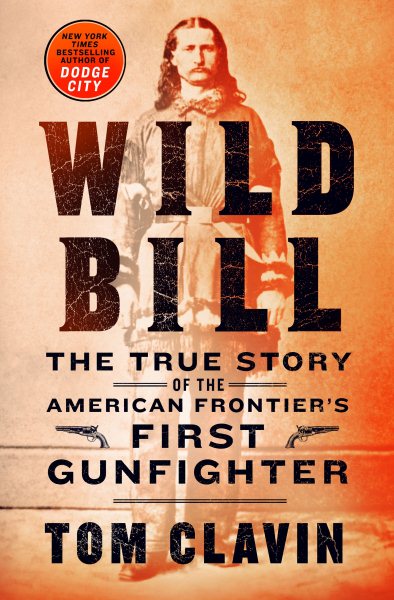

In a fast-paced page-turner, Philip Shirley weaves a tale of intrigue and nation-jumping that renews the debate over Elvis in the mystery novel  For those not especially knowledgeable about tales of the old frontier (other than movies and TV shows), Tom Clavin’s

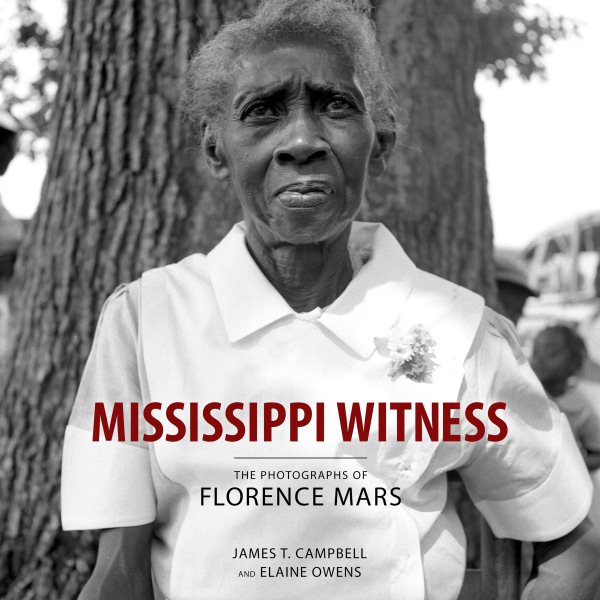

For those not especially knowledgeable about tales of the old frontier (other than movies and TV shows), Tom Clavin’s  But perhaps little known until now with the publication of

But perhaps little known until now with the publication of  In

In  It’s a fascinating voyage into the Golden Age of Piracy that not only proves true some of the stereotypes of legend, book and film, but also debunks others and shockingly reveals the depth of early America’s connection to the outlaw seafarers.

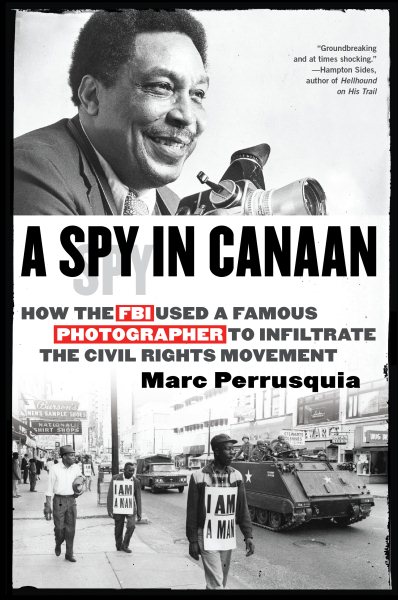

It’s a fascinating voyage into the Golden Age of Piracy that not only proves true some of the stereotypes of legend, book and film, but also debunks others and shockingly reveals the depth of early America’s connection to the outlaw seafarers. As a reporter for The Commercial Appeal, Perrusquia caught wind of a tantalizing story: that one of Memphis’ most well-known and respected Beale Street residents who had rubbed shoulders with the highest leaders of the movement was for nearly 20 years an FBI informant.

As a reporter for The Commercial Appeal, Perrusquia caught wind of a tantalizing story: that one of Memphis’ most well-known and respected Beale Street residents who had rubbed shoulders with the highest leaders of the movement was for nearly 20 years an FBI informant. James A. McLaughlin’s

James A. McLaughlin’s

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events. In

In