Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 10)

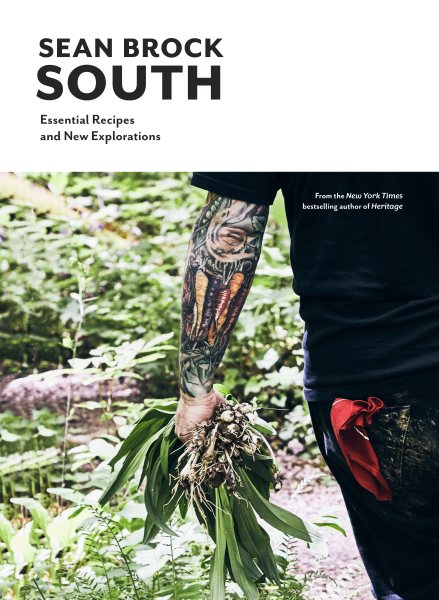

Sean Brock, the James Beard Award-winning author of Heritage follows up his nationally acclaimed debut book with a decidedly enthusiastic probe into the nurturing and connecting qualities of his favorite cuisine with South: Essential Recipes and New Explorations.

Sean Brock, the James Beard Award-winning author of Heritage follows up his nationally acclaimed debut book with a decidedly enthusiastic probe into the nurturing and connecting qualities of his favorite cuisine with South: Essential Recipes and New Explorations.

With an immutable passion for preserving and restoring heirloom ingredients, Brock offers up 125 recipes in South, with chapters that include everything from “Snacks and Dishes to Share” to “Grains,” “Vegetables and Sides” and even a section titled “Pantry,” complete with recipes and tips for preserving and canning–not to mention two full pages on “How to Make Vinegar.”

Sean Brock

Brock was the founding chef of the award-winning Husk restaurants and is now the chef and owner of Audrey, a distinctly unique dining destination set to open in east Nashville next year.

Brock has been recognized with the James Beard Award for Best Chef Southeast in 2010 and was a finalist for Outstanding Chef in 2013, 2014, and 2015. He has appeared on the TV series Chef’s Table and The Mind of a Chef, for which he was nominated for an Emmy.

Raised in rural Virginia Brock now lives in Nashville.

You made a national name for yourself crafting the heritage cuisine of the award-winning Husk restaurants in Charleston and Greenville, South Carolina; Savannah, Georgia; and Nashville. Tell me about your decision to shift gears and settle in Nashville as you start a new chapter of your life and career.

After my son was born, I had a health scare the last couple of years. I realized that I have to take better care of myself. I was working way too much and I worried way too much. I was operating eight restaurants in five cities. Finally, I had to say “goodbye” to that chapter and start a new path.

Your first book, Heritage, won the James Beard Award for Best American Cookbook and the IACP Julia Child First Book Award, and was called “the blue ribbon chef cookbook of the year” by The New York Times. Were you surprised by its huge success, and would you say that this achievement that helped change your career path?

I can hardly fathom that I ever even got a book deal–and that there would be so much interest in what I was doing with food.

Writing a book is really scary. With my first book, I knew I had one shot to get it out there the way I wanted. There is a gap of about a year between writing a book and getting it published–and a lot can happen in between. Once it’s out there, it’s out there. All I could do was cross my fingers and hope people would get into it. I remember holding it in my hands after it first came out, and seeing others holding it in their hands. That’s when it became real to me.

Winning the James Beard Award was such a stretch that I could have never even imagined it. I remember that day and what a whirlwind of excitement it was.

I think that book came out at a perfect time in America because I began to realize people were really, really interested in Southern food. As a place, it has many cuisines, not just one. It has a strong historical aspect that affects its preset and future.

You have said that you believe Southern cuisine ranks among the best in the world. Please tell me about South, and your motivations for writing it. What message do you want this book to convey?

It’s about how we all can contribute to our own food history. The way I see it, place has its own ingredients and its own cultural influences and natural geography. That’s how cuisine is shaped–restoring the old so we can now have the new. We look to many cultures much older than ours and how they handled their ingredients. It’s important that we can all contribute something to our own culinary history.

You grew up in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia, and attended cooking school in Charleston while you were still a teenager. What influenced your early culinary interests at such a young age?

I grew up living with my grandmother for a while. I was around 11 to 14 years old at that time, and those were such formative years. I loved eating at her table and being in her garden. It gave me a different perspective about food, and I just fell in love with it.

I started working in (restaurant) kitchens at age 15. Food Network had just started on TV, and that was where I began to see that side of food preparation as a more serious craft.

Thanks to my grandmother, I learned the power of food to nurture and comfort, and I never wanted to do anything else.

Sean Brock will be at Cathead Distillery on Thursday, November 14, a5 5:00 p.m. in conversation with John Currence to sign and discuss South: Essential Recipes and New Explorations.

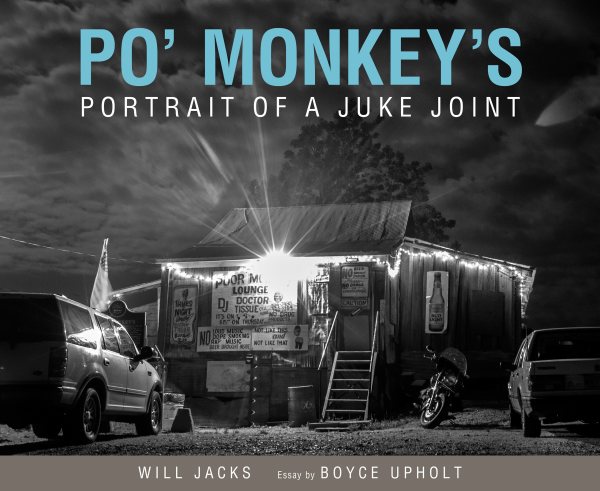

After decades of those-who-know-don’t-need-to-ask operation catering to locals in search of a Thursday evening respite, the establishment rose to prominence as white photographers and journalists enthralled by its authenticity brought news of its existence to their audiences, turning it into a must-see site for blues tourists traveling the Mississippi Delta.

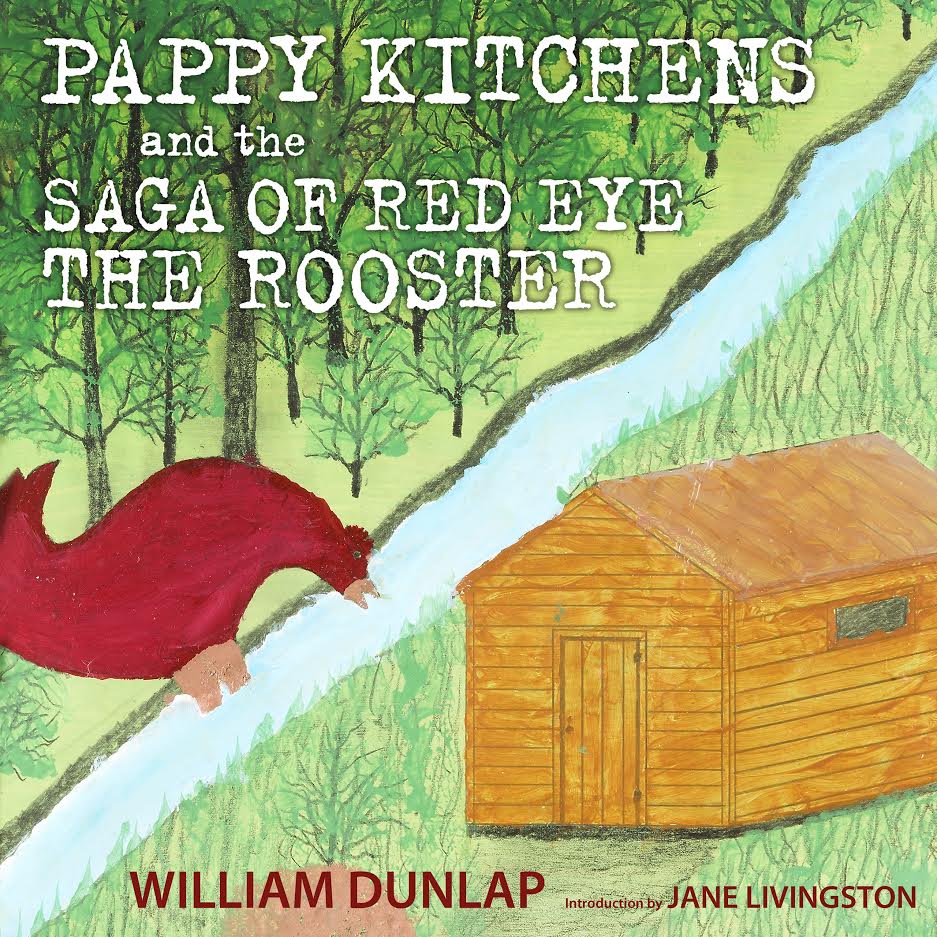

After decades of those-who-know-don’t-need-to-ask operation catering to locals in search of a Thursday evening respite, the establishment rose to prominence as white photographers and journalists enthralled by its authenticity brought news of its existence to their audiences, turning it into a must-see site for blues tourists traveling the Mississippi Delta. O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist.

O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist. The resulting book from this author, photographer and artist is

The resulting book from this author, photographer and artist is

Stories From 125 Years of Ole Miss Football

Stories From 125 Years of Ole Miss Football

Reverberations remain from decades during which Southerners acted as if the Civil War was not concluded with the Confederacy losing. The narrative evolved through variations on a theme, but constant was diversion from discussion of a multiracial society.

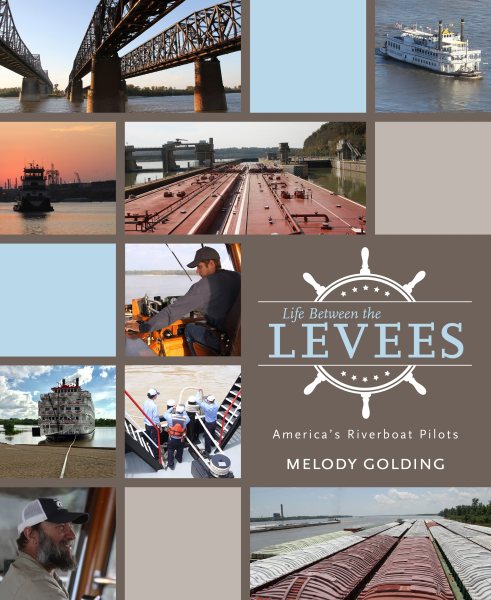

Reverberations remain from decades during which Southerners acted as if the Civil War was not concluded with the Confederacy losing. The narrative evolved through variations on a theme, but constant was diversion from discussion of a multiracial society. In her debut book

In her debut book