By Jim Ewing. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (April 29)

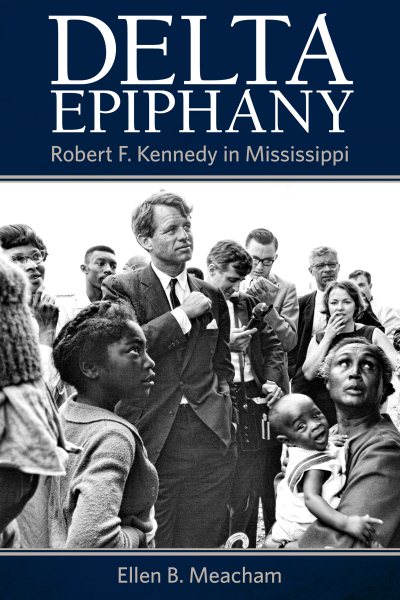

Ellen B. Meacham’s book, Delta Epiphany: Robert F. Kennedy in Mississippi, lives up to its title as a detailed recounting of the former U.S. senator and presidential candidate’s visit to the Magnolia State in April, 1967.

But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor.

But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor.

For starters, Meacham recounts the context of the times that saw riots in the nation’s largest cities as racial segregation and economic inequality ran rampant in the land, as the civil rights movement was moving turbulently forward, buffeted by murders and assassinations.

She sketches the major players in the national debate, not only Robert Kennedy, but the legacy of his slain brother, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson, who was trying to implement a War on Poverty, even as a shooting war in Southeastern Asia itself was taking a bloody toll and spurring protest.

She offers a Mississippi-centric view, naming the local players, including such well-known personas (considered moderates) as Congressman Frank Smith, journalist Bill Minor, political stalwarts William Winter and J. P. Coleman, and their complicated relationships with their sometimes foes, Wirt Yerger, Ross Barnett and Sen. James O. Eastland, among others.

On a lighter note, she even details the seating arrangements of the dinners, the hostesses, and guests of the entourage as Kennedy visited, making Epiphany a holistic, personal, textured, vivid, almost surreal memory of the time.

Kennedy’s trip was spurred by a confluence of factors, including the complexities of concern over the North’s urban ghettoes and the South’s Great Migration of blacks fleeing Jim Crow and dwindling jobs in the South.

Not the least of those influences, she reveals, was the young Marian Wright (who later married one of his aides, Peter Edelman, and founded the Children’s Defense Fund). Wright operated out of a cramped office above a pool hall on Jackson’s Farish Street. It was her assertion to Kennedy that people were literally starving in Mississippi. She implored him to see for himself.

He did.

In Cleveland, as shown by graphic, heart-rending photos, Kennedy found a family of 15 living in a shack. He asked a nine-year-old boy what he had eaten that day and he replied, simply, “molasses.”

Though it was afternoon, and he had only eaten that morning, his grandmother said, “I can’t hardly feed ’em but twice a day.” And then, the evening meal would only be more syrup, and bread.

It got worse. He saw people living in a shack with only a hole in the floor for a toilet. Their street was mud. For heat was a woodstove burning whatever they could find. With no furniture, their bed was a mattress on bricks. A child lying on it had open sores.

“Children, even babies, were near starvation in the heart of the richest country in the world.”

Meacham chronicles the visit by an American political icon only one year before his assassination, but she goes beyond that, revisiting the region and finding poverty still more than twice that of the rest of the nation; high school dropout rate 43 percent; 70 percent of births to single mothers; infant deaths among the highest.

Even food insecurity remains the second highest nationally. Some 208,530 people “have to choose between paying bills or buying food.”

Epiphany is a moving portrait of a wrenching time in the history of America, the South, Mississippi. It captures an enduring moment of national shame but still begs the question: Has society progressed so much since then?

Or, have we lost our way.

Jim Ewing, a former writer and editor at The Clarion Ledger, serves on the governing board of the USDA’s Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SSARE) program. He is the author of seven books, including Conscious Food: Sustainable Growing, Spiritual Eating.

Ellen Meacham will be at Lemuria on Tuesday, May 1, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from Delta Epiphany: Robert F. Kennedy in Mississippi.

It draws heavily from the verified facts about the former Varina Howell of Natchez, but is seamlessly layered with the insightful thoughts and personality of a woman from an attractive belle to an arch and wise matron in her later years. It’s truly a fascinating journey.

It draws heavily from the verified facts about the former Varina Howell of Natchez, but is seamlessly layered with the insightful thoughts and personality of a woman from an attractive belle to an arch and wise matron in her later years. It’s truly a fascinating journey. Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale.

Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale. Titled

Titled  Subtitled “What Men Need to Know (And Women Need to Tell Them) About Working Together,” the former chief content officer of Gannett and editor-in-chief of USA Today offers an eye-opening book about workplace inequality including to-the-point life lessons that are, at times, cringe worthy, humorous and profound. (Full disclosure: I worked briefly at USA Today in the 1980s and left the Gannett-owned Clarion-Ledger in 2012, before she joined the company.)

Subtitled “What Men Need to Know (And Women Need to Tell Them) About Working Together,” the former chief content officer of Gannett and editor-in-chief of USA Today offers an eye-opening book about workplace inequality including to-the-point life lessons that are, at times, cringe worthy, humorous and profound. (Full disclosure: I worked briefly at USA Today in the 1980s and left the Gannett-owned Clarion-Ledger in 2012, before she joined the company.) It’s a “crime” novel because it swirls around the notorious, real life crimes of an ax murder spree and wave of street robberies that struck 1918 New Orleans.

It’s a “crime” novel because it swirls around the notorious, real life crimes of an ax murder spree and wave of street robberies that struck 1918 New Orleans. For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book

For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book  It helps if you’re a hopeless romantic who thrives on the razor’s edge of hope and despair, not caring if ultimately successful in the target of your desires, for having experienced the compounding joys of the attempt, even if it’s dashed.

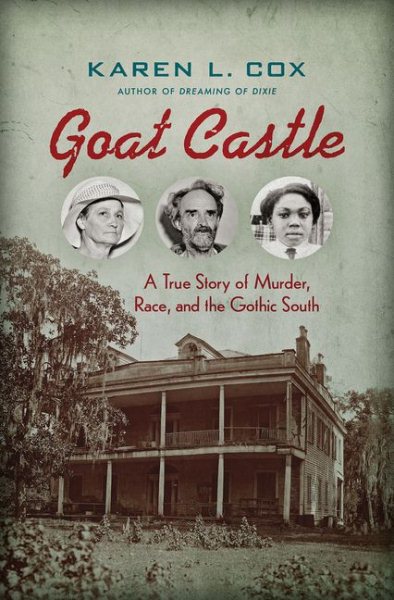

It helps if you’re a hopeless romantic who thrives on the razor’s edge of hope and despair, not caring if ultimately successful in the target of your desires, for having experienced the compounding joys of the attempt, even if it’s dashed. Addressing the Aug. 4, 1932, murder of Natchez heiress Jennie Merrill at her antebellum home Glenburnie, Cox peels back the layers of sensationalism surrounding the case to reveal the hard truths of racism and Jim Crow justice of the time.

Addressing the Aug. 4, 1932, murder of Natchez heiress Jennie Merrill at her antebellum home Glenburnie, Cox peels back the layers of sensationalism surrounding the case to reveal the hard truths of racism and Jim Crow justice of the time. The plot of Jennifer Egan’s latest novel

The plot of Jennifer Egan’s latest novel