Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 10).

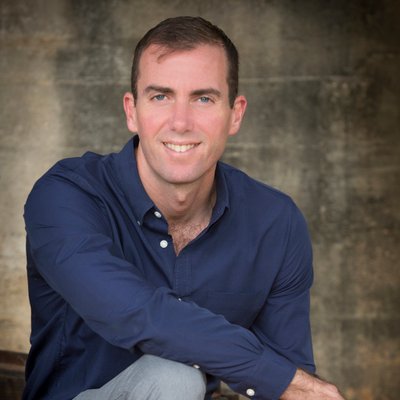

Louisiana native and journalist Ken Wells fondly recalls what he and his five brothers called “the gumbo life” in rural Bayou Black–a lifestyle lived close to the land and that meant he would not see the inside of a supermarket until he was nearly a teenager.

Louisiana native and journalist Ken Wells fondly recalls what he and his five brothers called “the gumbo life” in rural Bayou Black–a lifestyle lived close to the land and that meant he would not see the inside of a supermarket until he was nearly a teenager.

That phrase–Gumbo Life: Tales from the Roux Bayou–is the title of his culinary memoir which not only details the history of gumbo, but recounts recent stories of its role in today’s culture and kitchens.

Wells left Bayou Black decades ago to travel around the world as a writer for the Wall Street Journal, and he has penned five novels of the Cajun bayous. Today, he lives in Chicago.

In Gumbo Life, you describe gumbo as “more than a delicious dish: it’s an attitude, a way of seeing the world.” What exactly is gumbo, and can you tell us briefly about its diverse history?

In Louisiana, gumbo’s predominant interpretation is a café-au-lait colored soup cooked with a roux–flour browned in butter, oil, or lard–and served over white rice. Typically, ingredients include chicken, sausage, shellfish, okra, and a combination of vegetables known as the Trinity: celery, bell pepper, and onion.

Food historians think gumbo is at least 250 years old, probably older. The first written mention dates to New Orleans in 1764, and shows a dish called “gumbo fillet” or what we now know as file’ gumbo, being cooked by West African slaves. The Africans arrived with word-of-mouth recipes for spicy okra-and-rice stews that are the likely template for the first gumbos. In fact, the Bantu dialect word for okra is “gombeau”–probably how gumbo got its name.

An 1804 account by a French journalist has gumbo being served at a party in the Cajun bayous of southeast Louisiana. That reference fueled the myth of gumbo as a Cajun invention. But the Canjuns have played a critical role in gumbo’s evolution, specifically the roux. The most compelling theory is that the Cajuns, using animal fats that were ubiquitous in colonial cooking–bear lard, in particular–deployed the roux with such skill and gusto that today it is rare to find gumbos cooked without a roux.

You state that when you and your five brothers were “living the gumbo life” in Louisiana in the late 1950s, gumbo was pretty much “a Cajun and Creole secret, a peasant dish.” Tell us about gumbo’s rise in popularity around the world.

When I left the bayous for graduate school in Missouri in 1975, nobody there had a clue what gumbo was. Two things–the breakout of Cajun/Zydeco music to a national and world stage and the post-’70s boom in Louisiana tourism–began to change that. The music fueled an interest in the culture that produced it and, hence, the food that nourished it. Gumbo is…the only truly indigenous regional cuisine in all of America; not just a dish but a style and a way of cooking.

Ken Wells

Gumbo has traveled in part because of what I call the Cajun Obligation. My momma not only taught me to cook gumbo, but taught me that if you cook gumbo, you are required to share the love.

As a journalist, I’ve traveled over much of the world. I’ve cooked gumbo for friends in London; Sydney, Australia; and Cape Town, South Africa. The reviews are always the same: “How can anything be this good? Can you show me how to cook it?” I came to realize I was only the vessel stirring the roux. It’s what I call the Gumbo Effect: the dish itself. Gumbo, if you just stick to the plan with love and attention, transforms itself into food magic.

Gumbo Life is a deeply personal family story about growing up in a rural Louisiana setting where food and family were paramount. Living in points around the world since then (and Chicago now), and looking back, is it almost hard to believe how different life was for you then, compared to now?

I feel blessed. When we moved to our little farm on the banks of Bayou Black in 1957, I felt the place was happily stranded in the previous century. My dad worked for a large sugarcane-farming operation that still kept a mule lot–not entirely trusting all the plowing to tractors. My brothers and I learned to swim in the bayou. We got our water from a cypress cistern. The sugar company owned thousands of acres of marshland, fields, and woodlands that we were free to roam, hunt, trap, and fish. My brothers and I were in the 4-H Club and raised chickens and pigs that we entered in the annual 4-H Club fair–and harvested for the pot.

Food was central. My mom cooked Cajun–not just gumbo but dishes such as sauce piquant and court-bouillon with ingredients like snapping turtle and redfish that we harvested ourselves. We ate well! We grew a huge garden. I don’t think I set foot in a supermarket until I was 12 or 13 years old. That’s because there weren’t any near-by.

You book is also a history of one of Louisiana’s greatest cultural and culinary offerings to the world, along with glimpses of current gumbo tales that emphasize its adaptability–not to mention that you’ve included a glossary of regional and culinary terms, a map of the Gumbo Belt and 10 recipes! What did it mean to you personally to write this “culinary memoir”?

I obviously love my gumbo and I felt a deep exploration of its roots and iterations was a good way to tell the wider story of our singular, food-centric culture. I say “our” even though I have not lived in the Gumbo Belt since 1975, my journalism career having compelled me to living in big cities far away. I think that living away has helped me see my roots in a way that I might not have seen them had I stayed.

I have two grown daughters who, now in their 30s, love Dad’s gumbo as much as I loved my mother’s. But their childhoods could not have been more different than mine. We moved among cosmopolitan cities, lived abroad, traveled widely. They will never lead the gumbo life as I lived it and so in a way my book was written for them–to remind them of their connections to a place where our roots run so deep.

Ken Wells will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, March 13, at 5:00 to sign copies of and discuss Gumbo Life. Lemuria has chosen Gumbo Life as its March 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

The River

The River

But perhaps little known until now with the publication of

But perhaps little known until now with the publication of  The author’s newest book,

The author’s newest book,

Valeria Luiselli’s newest novel,

Valeria Luiselli’s newest novel,

On the Come Up returns to Garden Heights, the same neighborhood from The Hate U Give. This story is set on the the other side of the neighborhood, however. The effects of the climax of the last book are still being felt. Khalil’s death awakens political sensibilities, but these characters didn’t know him personally.

On the Come Up returns to Garden Heights, the same neighborhood from The Hate U Give. This story is set on the the other side of the neighborhood, however. The effects of the climax of the last book are still being felt. Khalil’s death awakens political sensibilities, but these characters didn’t know him personally. I was very excited to see a family tree in the first few pages. From Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to Yaa Gyasi’s

I was very excited to see a family tree in the first few pages. From Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to Yaa Gyasi’s