By Lisa Newman. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (February 3)

In Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive, the woman writes about the impact of the written word:

“When someone else’s words enter your consciousness like that, they become small conceptual light-marks. They’re not necessarily illuminating. A match struck alight in the dark hallway, the lit tip of a cigarette smoked in bed at midnight, embers in a dying chimney: none of these things has enough light of its own to reveal anything. Neither do anyone’s words. But sometimes a little light can make you aware of the dark, unknown space that surrounds it, of the enormous ignorance that envelops everything we think we know. And that recognition and coming to terms with darkness is more valuable than all the factual knowledge we may ever accumulate.”

Lost Children Archive is that light in the dark.

Lost Children Archive is that light in the dark.

A nameless family of four are on a journey from their home in New York City to the Southwest. The husband and wife met while working on a documentary project to collect the sounds of New York and have been married for four years, each with a child from a prior relationship. At the project’s conclusion, they have the freedom to pursue their own interests. The man aims to document the echoes of Geronimo and the Apacheria, and the woman will document the sounds of the lost children at the U.S.-Mexico border. The boy is given a Polaroid and will document their travels. The girl will be too young to remember much of the journey and will rely on her brother. The family members remain nameless while the woman narrates: “I, he, she, we: pronouns shifted place constantly in our confused syntax while we negotiated the terms of our relocation.”

The wife worries that without the New York project their relationship seems disconnected and knows that their paths will inevitably diverge. The boy and the girl are bonded and their relationship grows stronger as they travel down the road, while the husband and wife grow more detached. Along for the journey are seven metal boxes, which serve as windows into each character, filled with literature, notebooks, clippings and scraps, photographs, poetry, and maps.

The theme of being lost echoes throughout the novel: the woman reads aloud from Elegies for Lost Children; the boy and the girl pretend to be lost and become lost themselves; the little red book is lost; the border children are lost as their plane takes off, scattering them across the country away from their families. Even names are lost: the family is nameless until they earn a name in the Native American tradition, the names on the tombstones of the Native Americans are lost, erased by time. The only named characters in the novel are a group of lost children who must scream their names into existence.

While the woman narrates much of the novel, the young boy narrates a section and falls into stream of consciousness after he loses the little red book. Here the novel alludes to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in a section called Heart of Light, just one of many references to literature, music, and photography, including Carson McCullers’ The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, Vladimir Nabokov, Virginia Woolf, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid by Michael Ondaatje, the poems of Emily Dickinson, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies, and Sally Mann’s photography in Immediate Family.

The novel is a story of our time depicted in the story of the border children, but Lost Children Archive is also timeless as a coming of age story, a story about children finding their way in an adult-less world. Luiselli shows the vulnerability of human existence and frees the reader’s mind from political, cultural and societal influences and exposes what is truly at stake. Much like Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Luiselli releases the pressure of the adult world by presenting a child’s point of view to reveal the problem at its purest, most human point: “what happens if children are alone?”

Valeria Luiselli will be at the Eudora Welty House on Pinehurst Street on Thursday, February 14, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from Lost Children Archive. Lemuria has selected Lost Children Archive as one of our February 2019 selections for our First Editions Club for Fiction.

On the 20th anniversary of The Poisonwood Bible, Barbara Kingsolver gives us a timely novel in

On the 20th anniversary of The Poisonwood Bible, Barbara Kingsolver gives us a timely novel in  In the 1950s, the Beats adopted the form to publish poetry, most famously “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg and issued by Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights books in San Francisco. The Pocket Poet Series introduced avant-garde poetry to the masses and is still in print today. Broadside Press in Detroit supported the writers of the civil rights movement, publishing Margaret Walker’s “

In the 1950s, the Beats adopted the form to publish poetry, most famously “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg and issued by Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights books in San Francisco. The Pocket Poet Series introduced avant-garde poetry to the masses and is still in print today. Broadside Press in Detroit supported the writers of the civil rights movement, publishing Margaret Walker’s “ John Updike’s “The Women Who Got Away” (William B. Ewert, 1998) is an example of an embellished chapbook illustrated with woodcuts by Barry Moser. “Gwinlan’s Harp” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Lord John Press, 1981) and “

John Updike’s “The Women Who Got Away” (William B. Ewert, 1998) is an example of an embellished chapbook illustrated with woodcuts by Barry Moser. “Gwinlan’s Harp” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Lord John Press, 1981) and “

Bao Ninh features prominently in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s series on the Vietnam War. Ninh is a Vietnamese writer and former North Vietnamese soldier. Ninh’s novel,

Bao Ninh features prominently in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s series on the Vietnam War. Ninh is a Vietnamese writer and former North Vietnamese soldier. Ninh’s novel,  First published in Vietnam in a low-budget format by the Writers Association Publishing House of Hanoi in 1991, the book was translated into raw English by Phan Thanh Hao and rewritten by Australian war journalist and author Frank Palmos. At this point, the English translation was given the title “The Sorrow of War” and was published in Great Britain by Secker and Warburg in 1993 and in the United States by Pantheon in 1995.

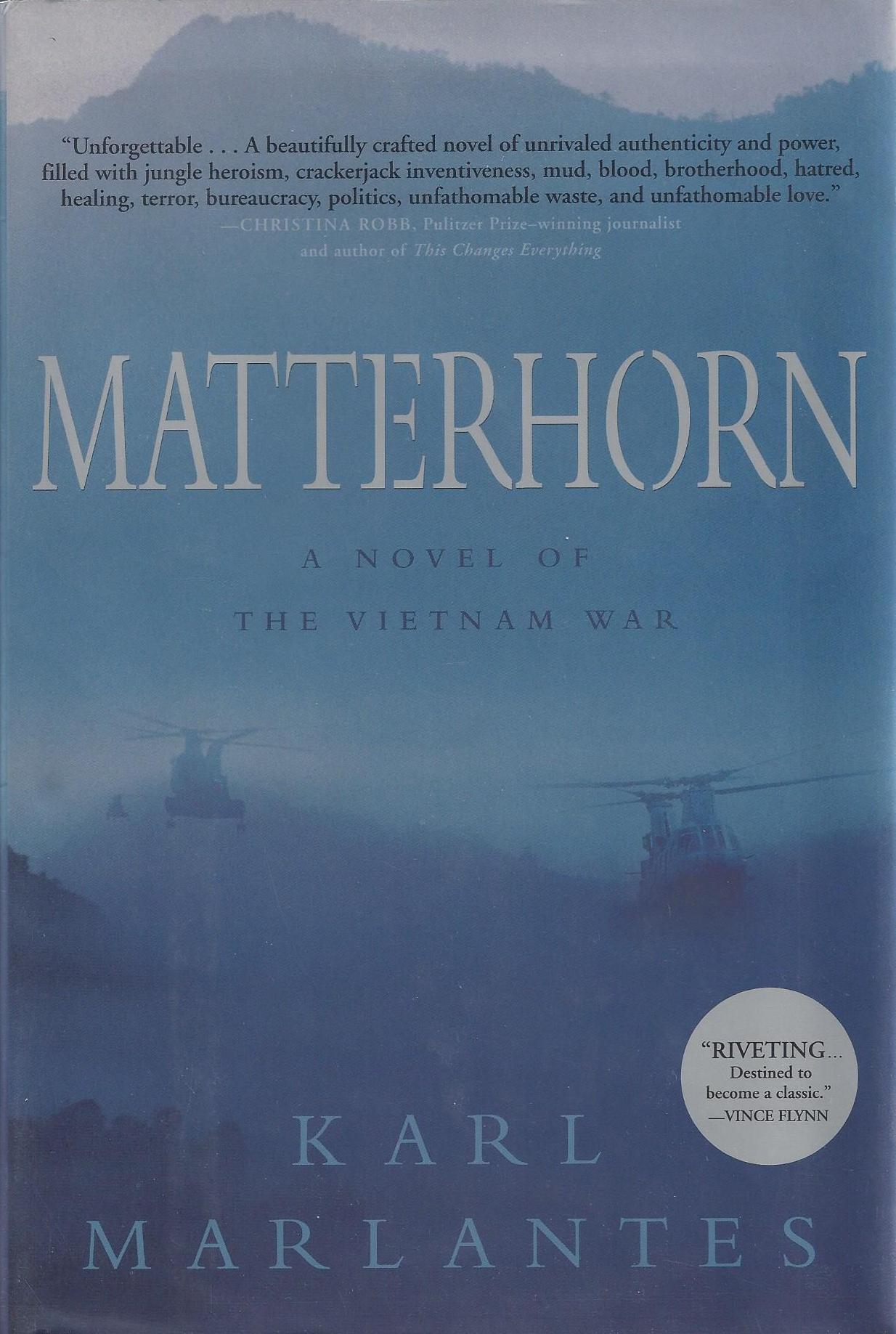

First published in Vietnam in a low-budget format by the Writers Association Publishing House of Hanoi in 1991, the book was translated into raw English by Phan Thanh Hao and rewritten by Australian war journalist and author Frank Palmos. At this point, the English translation was given the title “The Sorrow of War” and was published in Great Britain by Secker and Warburg in 1993 and in the United States by Pantheon in 1995. Karl Marlantes found a publisher in El Léon Literary Arts, a small press privately funded through donations. Led by author Thomas Farber, the operation is known to run on a $200 a year travel and entertainment budget and publishes literary works that might not seem commercially viable by mainstream publishers. By the time the 700-page Matterhorn was printed in softcover and review copies were sent out, a group of booksellers got the attention of El Léon by submitting Matterhorn to a first-novel contest. Soon Farber began getting calls from larger publishers. Eventually, a deal with the independent press Grove Atlantic was made and Matterhorn was released in hardback in 2010. Behind the scenes, Grove Atlantic’s Morgan Entrekin championed Matterhorn to booksellers across the country. The success of Matterhorn is due to the perseverance of its author, small presses, and the diligence of booksellers. It is a story of authenticity as opposed to overblown media hype.

Karl Marlantes found a publisher in El Léon Literary Arts, a small press privately funded through donations. Led by author Thomas Farber, the operation is known to run on a $200 a year travel and entertainment budget and publishes literary works that might not seem commercially viable by mainstream publishers. By the time the 700-page Matterhorn was printed in softcover and review copies were sent out, a group of booksellers got the attention of El Léon by submitting Matterhorn to a first-novel contest. Soon Farber began getting calls from larger publishers. Eventually, a deal with the independent press Grove Atlantic was made and Matterhorn was released in hardback in 2010. Behind the scenes, Grove Atlantic’s Morgan Entrekin championed Matterhorn to booksellers across the country. The success of Matterhorn is due to the perseverance of its author, small presses, and the diligence of booksellers. It is a story of authenticity as opposed to overblown media hype. This authenticity leads to a collectible book. The copies of Matterhorn printed in softcover at El Léon became advanced copies for Grove Atlantic’s hardcover edition. For collectors, that softcover is the true first edition. Matterhorn follows in the tradition of other great war novels like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line.

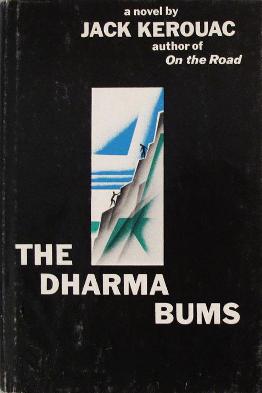

This authenticity leads to a collectible book. The copies of Matterhorn printed in softcover at El Léon became advanced copies for Grove Atlantic’s hardcover edition. For collectors, that softcover is the true first edition. Matterhorn follows in the tradition of other great war novels like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line. Jack Kerouac is synonymous with The Beat Generation which included Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady, Gary Synder, Herbet Edwin Huncke, and others. This generation of storytellers and poets explored the post-World War II culture, questioning America’s mainstream values, spirituality, religion, sexuality, and drug culture.

Jack Kerouac is synonymous with The Beat Generation which included Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady, Gary Synder, Herbet Edwin Huncke, and others. This generation of storytellers and poets explored the post-World War II culture, questioning America’s mainstream values, spirituality, religion, sexuality, and drug culture. In 1958 for “Pageant” magazine Kerouac would define Beat further as one who is in “a state of beatitude . . . trying to love all of life, trying to be utterly sincere with everyone, practising endurance, kindness, cultivating a joy of heart” despite our mainstream world of consuming and meaningless distraction.

In 1958 for “Pageant” magazine Kerouac would define Beat further as one who is in “a state of beatitude . . . trying to love all of life, trying to be utterly sincere with everyone, practising endurance, kindness, cultivating a joy of heart” despite our mainstream world of consuming and meaningless distraction. Jack Kerouac became an icon frozen in the early 1950s helped by his withdrawal from the public eye and his early death at the age of 47 in 1969. After his death, Allen Ginsberg promoted his work to a new generation. Generations since have redefined his work for their place and time. Kerouac is still relevant today not because he or his writing was flawless but for the simple reasons that he was a keen observer of human interaction—he was nicknamed “Memory babe” as a child, his work encourages an alertness to and questioning of the world around him, his writing showed people being brutally honest with each other—people who were comfortable “letting it all hang out,” and he was a writer who was real—“a writer who has been there” as Allen Ginsberg described in Kerouac’s obituary.

Jack Kerouac became an icon frozen in the early 1950s helped by his withdrawal from the public eye and his early death at the age of 47 in 1969. After his death, Allen Ginsberg promoted his work to a new generation. Generations since have redefined his work for their place and time. Kerouac is still relevant today not because he or his writing was flawless but for the simple reasons that he was a keen observer of human interaction—he was nicknamed “Memory babe” as a child, his work encourages an alertness to and questioning of the world around him, his writing showed people being brutally honest with each other—people who were comfortable “letting it all hang out,” and he was a writer who was real—“a writer who has been there” as Allen Ginsberg described in Kerouac’s obituary. Since a resurgence of interest in his work in the seventies, all of Jack Kerouac’s books have remained in print. First editions of his books are scarce and valuable among collectors. “The Dharma Bums,” largely considered to be his most accessible work, will sell for upwards of a $1000. His literary and personal archive were secured at the New York Public Library in 2001, and in 2007 Penguin published the original 120-foot scroll of “On the Road,” energizing Kerouac’s work for the next generation.

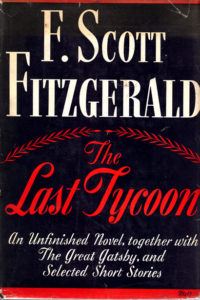

Since a resurgence of interest in his work in the seventies, all of Jack Kerouac’s books have remained in print. First editions of his books are scarce and valuable among collectors. “The Dharma Bums,” largely considered to be his most accessible work, will sell for upwards of a $1000. His literary and personal archive were secured at the New York Public Library in 2001, and in 2007 Penguin published the original 120-foot scroll of “On the Road,” energizing Kerouac’s work for the next generation. After his death in 1940, a longtime critic and friend Edmund Wilson secured permission from Fitzgerald’s family to publish “The Last Tycoon.” Wilson had never held back his negative criticism of the author’s work, even from Fitzgerald’s beginnings when Wilson published a satirical poem arguing that the young writer’s work was shallow and superficial. But Wilson was deeply affected by his death, expressing in a letter to Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda: “I feel myself as though I had been suddenly robbed of some part of my own personality.”

After his death in 1940, a longtime critic and friend Edmund Wilson secured permission from Fitzgerald’s family to publish “The Last Tycoon.” Wilson had never held back his negative criticism of the author’s work, even from Fitzgerald’s beginnings when Wilson published a satirical poem arguing that the young writer’s work was shallow and superficial. But Wilson was deeply affected by his death, expressing in a letter to Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda: “I feel myself as though I had been suddenly robbed of some part of my own personality.” Wilson, who must have felt some regret at being so critical of what he often called a “commercial” and “trashy” writer, decided to set the tone for Fitzgerald’s legacy by preparing his last manuscript and titling it “The Last Tycoon.” It would be published in book form accompanied strategically by “The Great Gatsby” and selected short stories. In the Foreword, Wilson announced “The Last Tycoon” to be “Fitzgerald’s most mature piece of work” and “the best novel we have had about Hollywood.” Other critics followed with similar praise. Novelist J. F. Powers asserted that “The Last Tycoon” contained more of his best writing than anything he had ever done and Fitzgerald’s best had always been the best there was.”

Wilson, who must have felt some regret at being so critical of what he often called a “commercial” and “trashy” writer, decided to set the tone for Fitzgerald’s legacy by preparing his last manuscript and titling it “The Last Tycoon.” It would be published in book form accompanied strategically by “The Great Gatsby” and selected short stories. In the Foreword, Wilson announced “The Last Tycoon” to be “Fitzgerald’s most mature piece of work” and “the best novel we have had about Hollywood.” Other critics followed with similar praise. Novelist J. F. Powers asserted that “The Last Tycoon” contained more of his best writing than anything he had ever done and Fitzgerald’s best had always been the best there was.” Fitzgerald’s influence, his attention to the illusive American dream, is seen in the work of Richard Yates, J. D. Salinger, Joseph Heller, and many contemporary writers. Mystery writer, Raymond Chandler, wrote that that “Fitzgerald is a subject no one has the right to mess up . . . He had one of the rarest qualities in all of literature . . . The word is charm—charm as Keats would have used it . . . It’s a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite.” While Fitzgerald had sold less than 25,000 copies of “The Great Gatsby” at the time of his death, this book has now sold over 25 million copies worldwide.

Fitzgerald’s influence, his attention to the illusive American dream, is seen in the work of Richard Yates, J. D. Salinger, Joseph Heller, and many contemporary writers. Mystery writer, Raymond Chandler, wrote that that “Fitzgerald is a subject no one has the right to mess up . . . He had one of the rarest qualities in all of literature . . . The word is charm—charm as Keats would have used it . . . It’s a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite.” While Fitzgerald had sold less than 25,000 copies of “The Great Gatsby” at the time of his death, this book has now sold over 25 million copies worldwide.