Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 29)

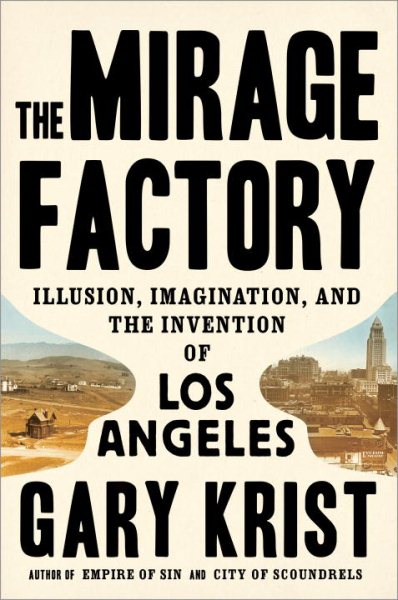

Gary Krist’s fascinating account of the history of Los Angeles during the first three decades of the 20th century puts a highly personal face on the mage-city’s early days through the almost unbelievable stories of three of its most interesting and important influencers in The Mirage Factory: Illusion, Imagination, and the Invention of Los Angeles (Crown Publishing).

Gary Krist’s fascinating account of the history of Los Angeles during the first three decades of the 20th century puts a highly personal face on the mage-city’s early days through the almost unbelievable stories of three of its most interesting and important influencers in The Mirage Factory: Illusion, Imagination, and the Invention of Los Angeles (Crown Publishing).

The stories of engineer William Mulholland, filmmaker D.W. Griffith, and evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson weave a dramatic and entertaining narrative that reveals much of how the unique culture and personality of today’s Los Angeles evolved.

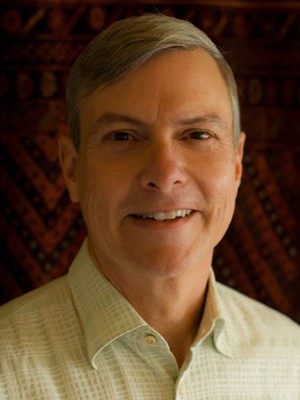

Krist also authored the bestselling Empire of Sin and City of Scoundrels as well as The White Cascade, along with five novels. HIs work has appeared in the New York Times, Esquire, the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post Book World, and other publications.

His work has earned honors that include the Stephen Crane Award, the Sue Kaufman Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Lowell Thomas Gold Medal for Travel Journalism, and others.

Gary Krist

Born and raised in Fort Lee, New Jersey, just across the river from Manhattan, Krist earned a degree in Comparative Literature from Princeton and later studied in Germany on a Fulbright Scholarship. He went on to live in New York City, then Bethesda, Maryland, for more than two decades before returning to his home state of New Jersey–where today, he and his wife Elizabeth Cheng now live in “an apartment in Jersey City right on the river looking out toward lower Manhattan.”

In your most recent books, you’ve written about New Orleans (Empire of Sin) and Chicago (City of Scoundrels). What led you to write about Los Angeles?

I see The Mirage Factory as the third of a trilogy of city narratives, the first two being, as you mention, the books about Chicago and New Orleans. It’s been fascinating to explore how each city grew and developed over time, each one coping with similar issues but in different ways, depending on the particular people and circumstances in each place.

What intrigued me about Los Angeles was the fact that this remarkable urban entity grew up in a place where no city should logically be. The area was too dry, too far from natural resources and potential markets; it was isolated by deserts and mountain ranges and without a good deep-water port. And yet it grew from a largely agricultural town of 100,000 in 1900 to a major metropolis of 1.2 million by 1930. That feat required imagination, not to mention some really unorthodox tactics–including plenty of deceptive advertising–and that’s the story I wanted to tell.

Please explain the title of the book.

The main point I wanted to convey in the title is that, granted, the city being promoted in the early 20th century was at first more image than reality, but eventually the hard work was done to make those mirages real. Since the site of Los Angeles lacked so many of the usual inducements to growth, city boosters trying to convince people and businesses to move to L.A. had to do a little creative salesmanship.

For instance, L.A. was advertised as a blossoming garden in the desert long before it had enough water to sustain that image; but eventually, through an enormous expenditure of creativity, effort, and money, it solved the problem by building the aqueduct. The city was also attracting too little industry; it solved this problem by more or less creating its own brand-new industry–motion pictures–a business literally based on selling images to the public.

So, while some people have interpreted the title too negatively, I see the term “mirage” as having both negative and positive connotations; a mirage, after all, stops being fraudulent when it actually takes physical form and becomes real.

The stories of the rise and fall of the figures you’ve chosen to highlight in this well-documented history of Los Angeles from 1900 to 1930 would probably be deemed almost unbelievable if they were fictional. In The Mirage Factory, you’ve chosen “three flawed visionaries,” as you called them, to tell the story of the city’s growth and cultural development during these years: engineer William Mulholland, filmmaker D.W. Griffith; and evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson. When you were conducting research for ideas, how did you settle on these three?

I always like to put a human face on the history I’m telling, so I try to focus on a few individuals whose stories allow me to discuss the important issues in a concrete way. these people are not necessarily the most influential figures in a city’s history, and they’re certainly not the individuals who “single-handedly” built the city–cities are always a group effort. But they must in some way be representative of the larger forces that DID build the city.

In the case of The Mirage Factory, I needed individuals to represent the three strands of the story I wanted to weave together–what I sometimes refer to as the water story, the celluloid story (i.e. Hollywood), and the spirituality story.

The first was a no-brainer; Mulholland was the dominant figure in L.A.’s water story for decades, and you really can’t tell the city’s history without him. For the celluloid story, I had a number of possible choices–Cecil B. DeMille, Charlie Chaplin, or on the studio heads like Adolph Zukor–but ultimately Griffith seemed to be the seminal figure, the person most responsible for taking the motion picture from a vaudeville house novelty to an industry-supporting art form. And as for McPherson, she may seem an obscure choice, since she’s not well known now; but in her day, she was at least as famous and influential as the other two, and she brought a large number of spiritually-seeking people to L.A.

Of course, the fact that all three of these people were fascinating individuals–with character flaws as big as their talents–was a definite bonus for me as a storyteller.

The city’s explosion in population from 1900 to 1930 was incredible, and you state that there were three main migrations to the city: the first being the well-off; the second primarily middle class; and third being those lower socioeconomic status who arrived hoping to become laborers. Tell me about the evolution of the city’s population as the years passed.

One thing that really surprised me when I was researching was how relatively homogeneous L.A.’s population was in the early decades of the 20th century, compared to that of other American cities. Given L.A.’ s current identity as a rich multicultural center, it was astonishing to me that the Los Angeles of the 1900s and 1910s still lacked large Latino, Asian, and African-American populations. That changed, of course, over the 1920s and 1930s, and especially during and after World War II. But until the 1920s, the city was drawing new residents largely from the well-heeled white populations of the Midwestern and Eastern states.

Taking each of the main characters individually, I’ll start with the contributions of Mulholland–an uneducated, self-taught man who would later be recognized as one of the leading engineers in the world. Why was his role so vital to the city’s existence and its future?

Mulholland was a phenomenon–a tireless autodidact with a remarkable memory and a prodigious work ethic who chose to devote his entire life to taking on the technical challenges of his adopted city. Every city should be so lucky. He was chief engineer of the Department of Water and Power, and its predecessor agencies, for decades, during which time he built the city’s water system up from essentially a small network of wooden pipes and open ditches. Really, the conception and construction of the L.A. Aqueduct was only one of his many feats.

The problem with Mulholland was that he began to believe the fastest and most efficient way to get things done was to do it all himself. As a result, he often proceeded without sufficient oversight and input from people who might have had more expertise in a specific area. In the end, that was the character flaw that led to the St. Francis Dam disaster and finished his career.

The role that D.W. Griffith played in the film industry was a major contribution to the city’s growth, providing thousands of jobs. What made his efforts to establish the industry in Los Angeles so successful?

Griffith essentially laid the groundwork for narrative motion pictures by taking many of the techniques being developed in the early years–close-ups, tracking shots, crosscutting–and combining them into a coherent and flexible grammar of visual storytelling. He didn’t invent those techniques, as he sometimes claimed, but he was uniquely successful at blending them to tell a powerful story.

As for turning movies into a major industry, though, it was the extraordinary financial success of his film The Birth of a Nation–as problematic as its racism was and is–that finally convinced Wall Street and the Eastern banks that movies were more than just a cottage industry–that they could be a big business comparable to steel, oil, and textiles.

The story of Aimee Semple McPherson is one I’ve never heard, but fascinating. Her evangelistic leadership played into and strengthened the city’s openness about spiritual matters. How is her influence still seen in the city?

McPherson’s extremely high profile in the 1920s and 30s allowed her to spread the word about Los Angeles as a center of often unconventional spirituality. Her unique combination of a positive and inclusive message with a heavy dose of arresting spectacle, including faith healing, speaking in tongues, dramatic illustrated sermons, and the like, became a powerful attraction for seekers of all kinds.

That legacy is preserved in the continuing relevance of the church she built–the Angelus Temple in the Echo Park neighborhood–and its outreach ministry, the Dream Center, which aids the city’s poor, homeless, addicted, and displaced. And the religion she founded, the Church of the Foursquare Gospel, now has over 6 million members worldwide.

During its early years, Los Angeles was in somewhat of a competition with San Francisco to become a leading and more influential American city, despite its location in the middle of a large desert. Why did L.A. win?

I wouldn’t say that San Francisco has really “lost” the competition, since it remains a hugely vital and influential city, but L.A. has outstripped it in size and, arguably, at least, in worldwide impact. It’s hard to say exactly why that happened, especially since San Francisco had such a long lead on L.A., developing as a city many decades earlier.

In a way, Los Angeles had to work harder. For instance, San Francisco had a superb natural harbor; L.A., on the other hand, had to undertake extensive improvements to make its harbor competitive. San Francisco had the enormous wealth created by the gold rush to jump-start its growth; L.A. had to figure out creative ways to bring investment and population to the city. So maybe it’s a matter of necessity being the mother of invention.

I’m a big fan of yours. do you already have a new writing project in the works?

I’m still in the early stages of research for the next project, but San Francisco attracts me as another, entirely different city whose history I’d like to explore. So maybe my trilogy of city narratives will become a quartet.

The Mirage Factory is Lemuria’s August 2018 selection for our First Editions Club for Nonfiction. Gary Krist will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival Aug. 18 as a participant in the American History panel at 10:45 a.m. at the C-SPAN room in Old Supreme Court Room at the State Capitol.

In

In  Although the settlers were on a mission to establish the first English colony in the New World, they disappeared without a trace while their leader was away on a six-month resupply trip that had stretched into three years. They left only one clue–a “secret token” carved on a tree.

Although the settlers were on a mission to establish the first English colony in the New World, they disappeared without a trace while their leader was away on a six-month resupply trip that had stretched into three years. They left only one clue–a “secret token” carved on a tree.

But mostly, it’s a tribute to his mother, 81-year-old Margaret Bragg, whose skills in the kitchen, he says, are still unmatched. This is a woman who never—not once—used a cookbook, a written recipe, a measuring cup or even a set of measuring spoons to put a meal on the table. Her skills came from oral recipes and techniques that go back generations—some even to pre-Civil War days.

But mostly, it’s a tribute to his mother, 81-year-old Margaret Bragg, whose skills in the kitchen, he says, are still unmatched. This is a woman who never—not once—used a cookbook, a written recipe, a measuring cup or even a set of measuring spoons to put a meal on the table. Her skills came from oral recipes and techniques that go back generations—some even to pre-Civil War days.

His newest book,

His newest book,

In a memoir about his duties with the patrol,

In a memoir about his duties with the patrol,

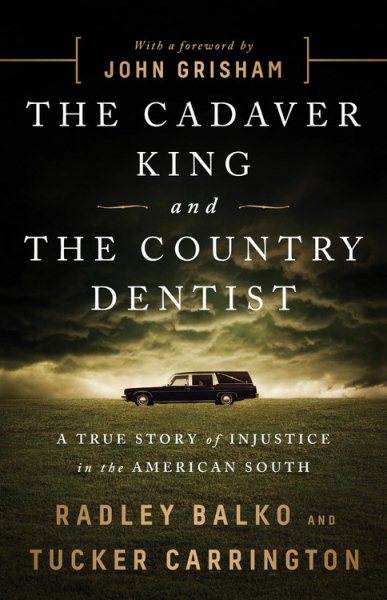

Their new book,

Their new book,