Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 15)

New York City photographer Isabelle Armand said she was “instantly inspired” to tell the stories of the wrongful convictions, incarcerations, and eventual exonerations of two rural Mississippi men when she first read about their cases more than five years ago.

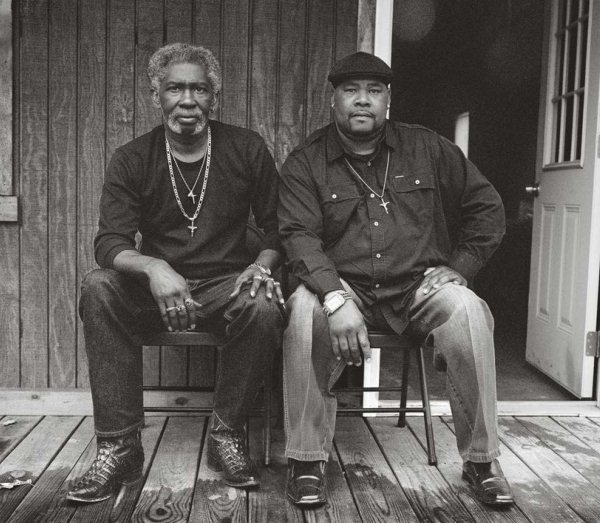

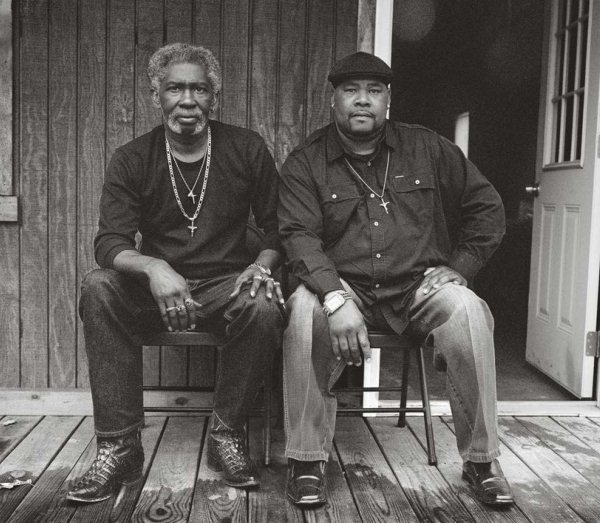

In her new book, Levon and Kennedy: Mississippi Innocence Project (PowerHouse Books), Armand has visually documented the everyday lives of Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer over a five-year period after their release from the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman. The black and white images of the men and their families, captured in and around their homes in the small rural Mississippi town of Brooksville, includes quotations that convey their thoughts and feelings of regret and joy about the miscarriage of justice and the eventual outcome of their cases.

In her new book, Levon and Kennedy: Mississippi Innocence Project (PowerHouse Books), Armand has visually documented the everyday lives of Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer over a five-year period after their release from the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman. The black and white images of the men and their families, captured in and around their homes in the small rural Mississippi town of Brooksville, includes quotations that convey their thoughts and feelings of regret and joy about the miscarriage of justice and the eventual outcome of their cases.

The men had been charged in separate murder cases committed 18 months apart in the early 1990s. Brooks was sentenced to life and was imprisoned 18 years; Brewer received a death sentence and served 15 years.

It was through the diligent work of The Innocence Project, along with DNA testing, that Brewere and Brooks were cleared of all charges and freed in 2008.

Armand’s book includes text by Tucker Carrington, director of the George C. Cochran Innocence Project at the University of Mississippi School of Law, who, with Washington Post reporter Radley Balko, co-authored the book The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist, also related to the cases of Brewer and Brooks.

Armand acknowledges the support of artist Olivier Renaud-Clement, the Shoen Foundation, PowerHouse Books, and Meridian Printing for the production of her book.

Her distinctive photography works can be found in private and museum collections, and have been exhibited in the United States. They have also been featured in national and international publications.

Tell me about your background, and how you became interested in photography.

I was born and raised in Paris. My mother was a Vogue editor and worked with amazing photographers such as Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin. We had many photography books of the masters. I was always around photography and got the best possible education. I was especially drawn to the works of Walker Evans, Dorthea Lange, Brassai, Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, Edward Curtis, who documented people and places. They were storytellers of life. But at first, I followed in my mother’s steps and worked as a stylist there, and here.

I left France at 20 to come to New York, which I still love some 30 years later.

Do you have family or other connections to Mississippi?

A lifelong inspiration would be my only connection to Mississippi. I grew up fascinated with the U.S.; at first, it was through cinema. The West, New York, and the South seemed mythical places.

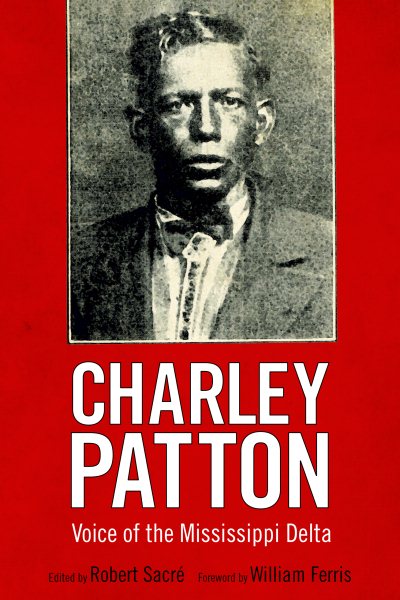

In Paris, I was around Blues musicians, and our idols were Robert Johnson, Little Walter, Muddy Waters, and the like. Mississippi captured my imagination, a fundamental American culture was born there, and I find the place incredibly rich and deeply textured.

How did you hear about the cases of Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer? When and why did you decide to become involved in them?

I came across an article about the cases’ forensics in 2012. It was a troubling account of a flawed and corrupt process, when reality goes beyond fiction. It triggered many questions; how, why, and where could this happen? I was instantly inspired to tell their story in photographs. I waited for several months, but the story stayed with me. Finally, I contacted Tucker Carrington, and suggested a photographic documentary around Levon’s and Kennedy’s experiences.

When did you begin photographing the images in this book, and how long did it take?

I began to photograph Levon and Kennedy and their families in June 2013. The last images and interviews were done in July 2017. I would go each year to spend time with them, take pictures, and collect interviews. With printing, editing both the images and the interviews, it took five years.

What were your goals (artistic and otherwise) for this project, as far as what you wanted to capture, how you envisioned the large photo collection would be organized, etc.?

The goal was to create a compelling visual essay to raise awareness about wrongful conviction. It’s a reality, which mostly remains abstract until we see it with our own eyes. I felt an intimate photo essay would bring the story of Levon and Kennedy to the forefront. We’d get to know them and their families like our own, and realize that the system can crush anyone.

I envisioned this essay pretty much like it is now. I started with retracing Levon’s and Kennedy’s childhoods, and visiting places which were meaningful to them, then and now. I’d document everyday life; family members, families’ gatherings, birthdays, July 4th, as well as their rural environment. With time, the project took a life of its own.

I love black and white film. It mutes unnecessary noise, and it sets off the essence of the subjects for me. Also, light on film is magic.

I edited as I went along, for each family, until editing for the book, when I had to look at the images in a new light. I eliminated a few photographs and created a new visual narrative. Damien Saatdjian, the graphic designer, gave it great breathing space and rhythm.

Both men and their families seem to have very forgiving spirits about their ordeals. Did that surprise you?

I knew a little about them prior to meeting them, so I wasn’t surprised. They were very angry when it happened. But spending 18 years in prison, or 10 on death row, they had to deal with it in a certain way, or it would destroy them. They had to make some peace with their situation, so they could endure and still be the men they wanted to be. Levon was thrown into a dangerous general population and chose to become a good influence. He saved lives and he was respected. Kennedy, isolated in his cell 24/7 while facing death, chose to educate himself, read, wrote, and prayed. Thinking of his ordeal every day was not an option, like he says in the book, “You’d go crazy.” Yet, he thought about it because he was trying to save himself, which he did by writing to the Innocence Project.

Besides where, how, and why this happened, my question was, “How does one and one’s family cope with wrongful conviction?” Both men and their families stick to a strong philosophy of life.

Levon and Kennedy have large families who supported them during their incarcerations, and you got to know them during the course of this project. What can you tell me about them–their thoughts on their loved ones’ false imprisonment, their attitudes about living in their rural Mississippi communities, their hopes for their own futures and that of their children and grandchildren? (It’s notable that, although many of them mentioned racial prejudice as an everyday event, most prefer to stay because of close family ties and the “peace and quiet” they enjoy.)

I interviewed everyone for the quotes you see in the book, and it depends on the individual. Most feel that the criminal justice system needs major changes. They lived through the most tragic consequences of this system, and their community still does in many ways. Levon and Kennedy’s wrongful incarceration is something they all want to put behind them, even though they have strong opinions about it.

These families have been there for generations, they are attached to their land loved ones, and most don’t want to leave. Some of the younger people are torn between the desire to go places offering more opportunities and diversity, and their love for their family and area. Every parent hopes for a better future for their children, but few think things will change in Mississippi. However, they all go about living their full lives. They ignore and rise above external pressures.

Sadly, Levon passed away this past January, after 10 years of freedom. Did he get to see this book?

Levon was the first person to receive the book right from the printer. He took it all around town, and he was proud of it.

The way the book is bound is wonderful–I love the way the book itself is the book jacket! As an artist, tell me about the decision to create this book like this, in that it makes such a strong impression before it’s even opened!

I don’t like jackets on books and I wanted the cover printed with a discreet lamination. I didn’t want any typo on the cover, either. I felt Levon and Kennedy were so powerful in this photograph that they drew you in. The book wouldn’t be what it is without the work of my lab Laumont on the book files, and the amazing printing of Meridian Printing. And again, Damien Saatdjian’s input was also invaluable to achieve the results we wanted.

Isabelle Armand will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival Aug. 18 as a participant in the “Seeing the Light in Mississippi” photography panel at 4:00 p.m. at the Galloway Fellowship Center.

I was very excited to see a family tree in the first few pages. From Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing, some of my very favorite novels have been multi-generational family sagas, books that allow you to hear the echoes of the past. This book did not disappoint on that front.

I was very excited to see a family tree in the first few pages. From Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing, some of my very favorite novels have been multi-generational family sagas, books that allow you to hear the echoes of the past. This book did not disappoint on that front.

In fact, Isbell’s monumental work is a response to Katrina and the resiliency of our coastal institutions and residents. As a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer, he chronicled the destruction of the hurricane for The Sun Herald, the Gulfport/Biloxi-based daily newspaper. Isbell explains in his introduction to the The Mississippi Gulf Coast that the work has “special meaning, as it was a therapeutic endeavor after the destruction from Hurricane Katrina.”

In fact, Isbell’s monumental work is a response to Katrina and the resiliency of our coastal institutions and residents. As a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer, he chronicled the destruction of the hurricane for The Sun Herald, the Gulfport/Biloxi-based daily newspaper. Isbell explains in his introduction to the The Mississippi Gulf Coast that the work has “special meaning, as it was a therapeutic endeavor after the destruction from Hurricane Katrina.” Too often it takes years, but right can triumph over wrong. In

Too often it takes years, but right can triumph over wrong. In

In her new book,

In her new book,

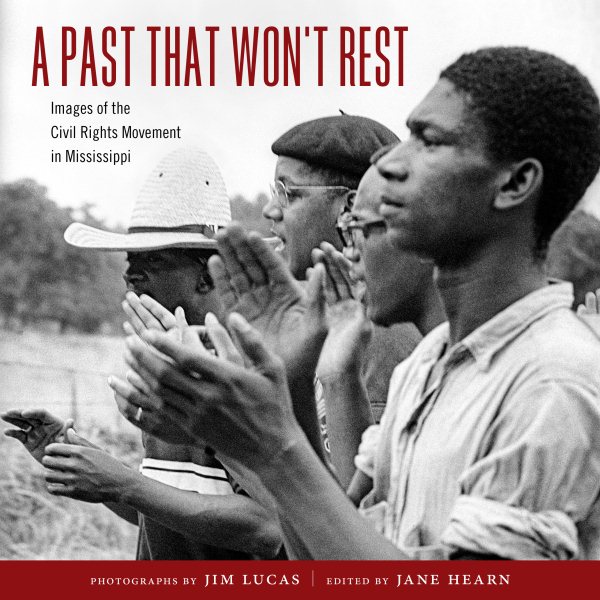

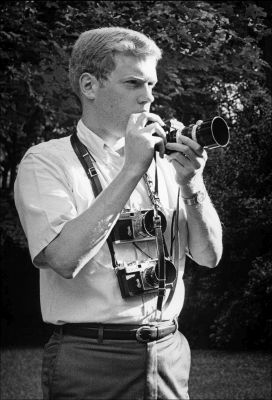

The University Press of Mississippi publication features more than 100 never-before-seen photographs taken by Lucas from 1964 to 1968 that focus on four Mississippi historic events, with a fifth chapter putting recent national episodes of activist violence into historical perspective. These chapters are bolstered with narratives contributed by Dr. Howard Ball, Peter Edelman, Aram Goudsouzian, Robert E. Luckett Jr., Ellen B. Meacham, and Stanley Nelson, with a foreword by Charles L. Overby.

The University Press of Mississippi publication features more than 100 never-before-seen photographs taken by Lucas from 1964 to 1968 that focus on four Mississippi historic events, with a fifth chapter putting recent national episodes of activist violence into historical perspective. These chapters are bolstered with narratives contributed by Dr. Howard Ball, Peter Edelman, Aram Goudsouzian, Robert E. Luckett Jr., Ellen B. Meacham, and Stanley Nelson, with a foreword by Charles L. Overby.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events. Such is the wonder and the power of

Such is the wonder and the power of  Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale.

Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale.