By Jim Ewing. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (October 1)

In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book of essays We Were Eight Years in Power (One World), he recalls that he felt at odds with himself when penning the first one for The Atlantic in 2007.

In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book of essays We Were Eight Years in Power (One World), he recalls that he felt at odds with himself when penning the first one for The Atlantic in 2007.

Barack Obama was running for president but, as a black man, was hardly thought then to be a full-on contender. Coates’ feeling of being adrift was shared with young black men and women across the country. They were “lost in a Bermuda triangle of the mind or stranded in the doldrums of America.”

Obama’s election changed that, he writes. But it also changed the nation’s dialogue on race, one that continues with an urgency underscored by the headlines of the day.

The book is composed of the eight essays he wrote for The Atlantic during each of the eight years of the nation’s first black presidency, along with current commentary. But it is Reconstruction in the South that the title of the book refers to, quoting W.E.B. DuBois, that: “If there was one thing… (whites) feared more than bad Negro government, it was good Negro government.”

With the rise of Donald Trump after a period of “good Negro government,” it can be argued we are witnessing from Washington and much of the country that frame of mind today. It’s manifested in displays by sports figures taking a knee in solidarity against police brutality against blacks, racial profiling, social inequality, disparities in education and opportunity, fueled by a president who finds no qualm in siding with Nazi protesters while calling those who demonstrate against it “sons of bitches.”

Before Obama, the idea of a black president lived as “a kind of cosmic joke,” Coates writes. “White folks, whatever their talk of freedom and liberty, would not allow a black president.” Witness, Emmett Till’s audacity to look at a white woman, the fact that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “turned the other cheek, and they blew it off.”

Lincoln was killed for emancipation, Freedom Riders were beaten for advocating for voting rights, Medgar Evers was shot down in his driveway “like a dog.”

“That a country that once took whiteness as the foundation for citizenship would elect a black president,” Coates writes, “is a victory. But to view this victory as racism’s defeat is to forget the precise terms on which it was secured.”

It encapsulates a paradox: America couldn’t elect “a black man,” but it could elect a qualified man who was black–as long as he didn’t evince blackness.

Coates’ outstanding previous book, Between the World and Me, was as much a plea for understanding race consciousness as a denouncement of racism in America.

The question it raised in 2015: Is this plea heard? By whom? And are the intractable problems of race solvable by a society founded on centuries of racial and economic inequality?

In Power, the pleas are gone. Instead, with its contextualizing commentary, it’s a questioning odyssey throughout the Obama years and now of the fact of racial polarization and misunderstanding that colors all attempts at recognizing progress or reversal. It’s an indictment of a nation where even black citizens who hold conservative, mainstream values are turned away from the party that espouses them because of its open appeals to people who hate them.

Power is an exploration in many ways to explain how a society based on Enlightenment values could ignore its essential white supremacy, that the foundational crimes of this crimes of this country are to somehow be considered mostly irrelevant to its existence, as well as those excluded and pillaged in order to bring those values into practice.

Through troubling to read, the aggregate is a journey of wonder, even when topics are troubling, for the deep mental explorations they offer, often without road map or easy conclusions.

Power is an exemplary, perhaps even vital, addition to the national dialogue on race in America.

Jim Ewing, a former writer and editor at The Clarion-Ledger, is the author of seven books including his latest, Redefining Manhood: A Guide for Men and Those Who Love Them.

The characters are built slowly, as the chapters flit between events in Germany, France, Italy, and Israel in 2002 and 2014. In the beginning, we don’t know the identity of Prisoner Z, or about the crime he committed to land him in prison.

The characters are built slowly, as the chapters flit between events in Germany, France, Italy, and Israel in 2002 and 2014. In the beginning, we don’t know the identity of Prisoner Z, or about the crime he committed to land him in prison. All the familiar denizens of the fictional town of Jericho, Mississippi, (faintly like the Oxford we all know, perhaps stripped to its roots) are there–if not in person, then in memory.

All the familiar denizens of the fictional town of Jericho, Mississippi, (faintly like the Oxford we all know, perhaps stripped to its roots) are there–if not in person, then in memory. Every once in a while, a book comes along that is so simple, rich, textured and real that you know some invisible line has been crossed, that something new has been created that will live on to become a classic.

Every once in a while, a book comes along that is so simple, rich, textured and real that you know some invisible line has been crossed, that something new has been created that will live on to become a classic. Novelist John Grisham keeps churning out winners that manage to wrap social issues, the law, and intriguing characters into an explosive mix, with his latest, The Whistler, sure to be a controversial bestseller like many before.

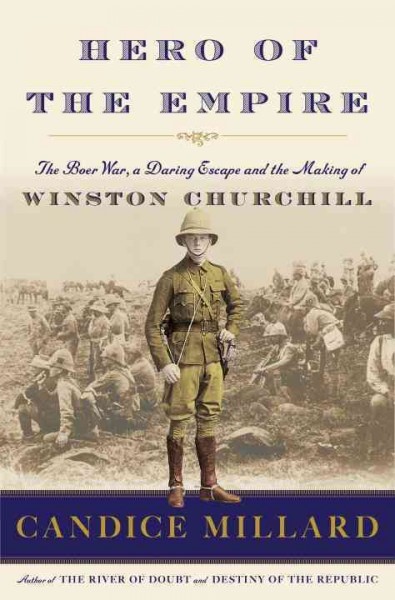

Novelist John Grisham keeps churning out winners that manage to wrap social issues, the law, and intriguing characters into an explosive mix, with his latest, The Whistler, sure to be a controversial bestseller like many before. With Candice Millard’s latest biography

With Candice Millard’s latest biography