Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (May 19)

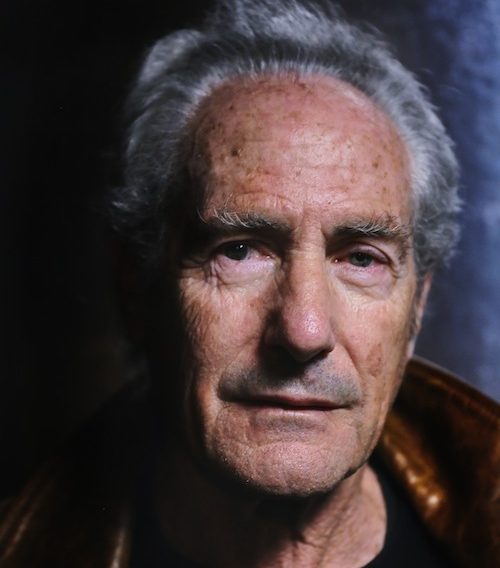

Chicago native Barry Gifford began writing at age 11 – partly because his childhood (mostly spent living in hotels around the country, including the old Heidelberg in Jackson) offered up a constant cast of “characters” with their own endless stories to tell.

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing.

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing.

Gifford’s latest pair of readers include cozy “reruns” of familiar stories that have been reformatted to make it easier for old and new fans to binge-read some of his best work at a relaxed pace.

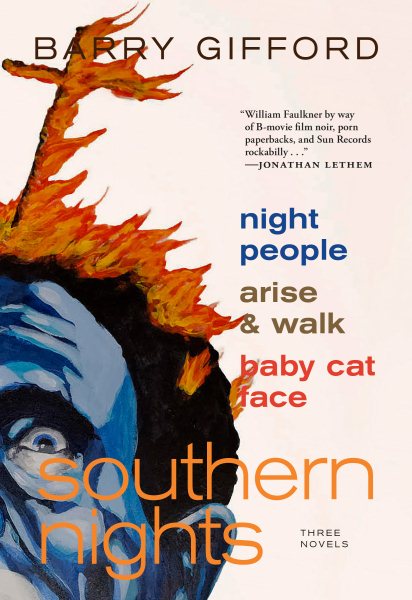

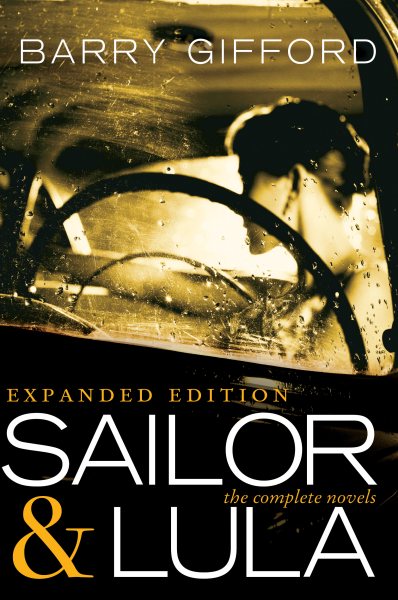

Southern Nights offers up a Southern Gothic trilogy while Sailor and Lula: Expanded Edition places all eight installments of this couple’s romance and adventures in one laid-back volume.

“My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

“My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

His works of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry have appeared in many publications, including The New Yorker, Esquire, La Nouvelle Revue Française, El País, La Republica, Rolling Stone, Film Comment, El Universal, and the New York Times. He has received awards from PEN, the National Endowment for the Arts, the American Library Association, the Writers Guild of America, and the Christopher Isherwood Foundation.

His film credits include Wild at Heart, Perdita Durango, Lost Highway, City of Ghosts, Ball Lightning, and The Phantom Father. He has also written librettos for operas composed by Toru Takemitsu, Ichiro Nodaira, and Olga Neuwirth.

Today Gifford lives in California.

Below, he shares comments about his newest releases.

Tell me about your dichotomous growing-up years [living in both the “Deep South” (and including here in Jackson) and in the “Far North,” a.k.a. Chicago] and how this has influenced your writing through the decades.

Barry Gifford

I was born in Chicago and moved to Key West, Fla., with my mother before I was a year old. She had health problems and was advised to live in milder climate. My father kept an apartment in the Hotel Nacional in Havana, so we visited him there.

Later I spent time in Tampa with an uncle who lived there; then my mother, after she divorced my father, had boyfriends in New Orleans and Jackson, so we spent time there and in Chicago, where I went to high school.

We lived mostly in hotels, including the old Heidelberg Hotel in Jackson.

Your recently released Southern Nights trilogy is a package of your Southern Gothic novels Night People, Arise and Walk, and Baby Cat-Face–packed with humor and drama lived out in a strange and straightforward sense of reality. When were each of these novels originally published, and how do their stories still apply to American culture today?

The Southern Nights trilogy was published as separate novels during the 1990s. They deal in an often satirical but deadly serious way with racism and fundamentalist religion. They’re tough, funny, and often violent, just like America.

Sailor and Lula: Expanded Edition is your newest release and contains every Sailor and Lula novel in the collection, including the eighth and last one, The Up-Down. How can you explain the enduring likability of these characters, despite their flaws, among your readers?

Sailor and Lula have been described as the Romeo and Juliet of the Deep South. I hope people keep reading about them as long as they keep reading Shakespeare.

You’ve had a long and incredibly successful career as a writer in several different genres (poetry, fiction, nonfiction, screen writing) and have developed a loyal following through the years. What do you think has continued to draw readers to your work?

I write in different forms about what interests me and never talk down to the reader. I like to think that, once in a while, I come close to telling the truth.

What can readers expect to see in future Barry Gifford works?

It’s possible that Sailor and Lula may be appearing soon in a TV series, with which I may have something to do. And I’ve got a novel-in-progress about Cassie Angola, a young African-American woman who appears as a little girl in the last of the Sailor and Lula novels, The Up-Down. Ask me this question again after I finish it!

I see that your current book tour includes just a handful of cities. I know you spent some of your childhood in Jackson, but you spent parts of your childhood in lots of places! How did Jackson make that limited list?

I’ve known (Lemuria Book store owner) John Evans for close to 30 years, and . . . for me, he represents the best of Jackson. Lemuria Books is a treasure.

Barry Gifford will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, May 22, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss Southern Nights and Sailor and Lula: Expanded Edition.

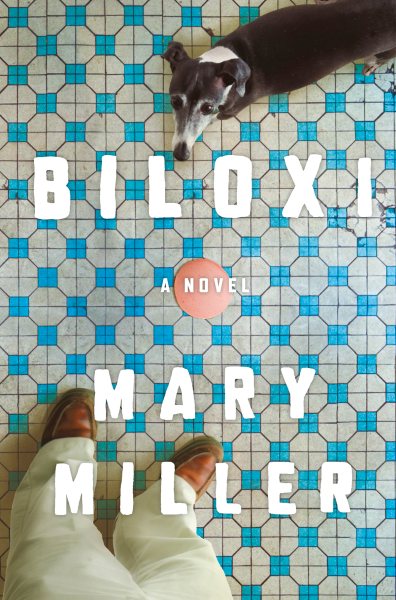

Oxford’s Mary Miller highlights a Mississippi coastal town with a thoughtful tale of a middle-aged man facing an uncertain and lonely future–until he adopts a dog on a whim and one thing leads to another.

Oxford’s Mary Miller highlights a Mississippi coastal town with a thoughtful tale of a middle-aged man facing an uncertain and lonely future–until he adopts a dog on a whim and one thing leads to another.

Casey Cep in

Casey Cep in  And yet. As Hungary and the citizens of the Engels’ town of Pecs, Hungary were overrun by Nazi forces in 1944, a century of prominence, good works and assumed assimilation weren’t enough for the Engels. The scion of the Pecs branch of the family—McMullan’s grandfather’s first cousin Richard Engel—died at the Mauthausen concentration camp after being rounded up along with other town Jews in March 1944. The story of Richard’s descent from respected, wealthy World War I war hero and city civic leader to being marched off as townspeople watched is the spellbinding story that McMullan tells in

And yet. As Hungary and the citizens of the Engels’ town of Pecs, Hungary were overrun by Nazi forces in 1944, a century of prominence, good works and assumed assimilation weren’t enough for the Engels. The scion of the Pecs branch of the family—McMullan’s grandfather’s first cousin Richard Engel—died at the Mauthausen concentration camp after being rounded up along with other town Jews in March 1944. The story of Richard’s descent from respected, wealthy World War I war hero and city civic leader to being marched off as townspeople watched is the spellbinding story that McMullan tells in

This is what bestselling author and Alabama native Helen Ellis calls “

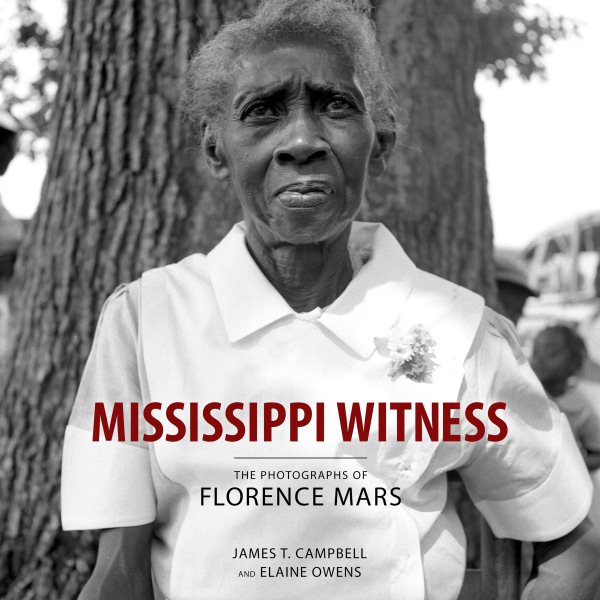

This is what bestselling author and Alabama native Helen Ellis calls “ Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars

Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars

Roommates in college, Helen and Charlie were opposite forces who became incredibly close. Helen was more scientific and analytical, a quiet woman who made herself known in the academic world, while Charlie was magnetic and outgoing. She was one of those people who everyone wanted to be around. After graduation, the women drifted apart. They both had children, Helen on her own and Charlie with a husband, and they made great strides in their professions. Helen became a theoretical physicist at MIT and published accessible books about physics, and Charlie became a screenwriter in Hollywood.

Roommates in college, Helen and Charlie were opposite forces who became incredibly close. Helen was more scientific and analytical, a quiet woman who made herself known in the academic world, while Charlie was magnetic and outgoing. She was one of those people who everyone wanted to be around. After graduation, the women drifted apart. They both had children, Helen on her own and Charlie with a husband, and they made great strides in their professions. Helen became a theoretical physicist at MIT and published accessible books about physics, and Charlie became a screenwriter in Hollywood.