Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (April 22)

Amidst a timely controversy about the relevance of Confederate monuments scattered across the South and a national discussion about race, Charles Frazier’s newest novel examines the role of Varina Davis, wife of the Confederacy’s only president, Jefferson Davis, and her influence on history.

In Varina, a work of historical fiction, Frazier places the former first lady of what he refers to as the “imaginary country” at a health resort in Saratoga Springs, New York. The year in 1906, and the story begins just weeks before her death at age 80, when she gets a surprise visit from a middle-aged African-American man she doesn’t recognize.

The stranger turns out to be the young boy she took in off the streets of Richmond 40 years ago, who is searching for clues about his own identity. As she recounts her story of the war years and beyond, he begins to clarify his personal history.

Charles Frazier

Frazier, who won the National Book Award for his internationally bestselling debut novel Cold Mountain in 1997, has said that he believes events of the past few years have left America still searching for a resolution to issues concerning race and slavery.

Frazier’s other novels include Thirteen Moons and Nightwoods. A native of North Carolina, he still makes his home there.

Why did you choose Varina Davis to write about now–was it influenced by the efforts of some today to remove statues of Confederate leaders, including her husband Jefferson David, president of the Confederacy?

I was interested in the fact that she left Mississippi shortly after Jefferson Davis died and moved to New York City to become a newspaper writer when she was over 60 years old. I found out that she had lived in London for some time, alone. As she grew older, she stayed engaged with the world around her and her opinions continued to evolve. At a time in life when most people start slowing down, she was digging her heels in, thinking mostly about her work, writing.

I was interested in the fact that she left Mississippi shortly after Jefferson Davis died and moved to New York City to become a newspaper writer when she was over 60 years old. I found out that she had lived in London for some time, alone. As she grew older, she stayed engaged with the world around her and her opinions continued to evolve. At a time in life when most people start slowing down, she was digging her heels in, thinking mostly about her work, writing.

The novel is crafted around the conversations of an aging Varina with a man she had apparently rescued as a child–a man she had not seen in 40 years. He has come to her for answers about his own identity, and she provides clues as she tells her story. At the time he visits, she is 80 years old and has been earning her living by writing for publications in New York City. Tell me about their relationship.

It’s not certain that she rescued him. The story that (Varina’s friend) Mary Chesnut told was that Varina was riding through Richmond in a carriage and she witnessed the boy being mistreated and took him in; there is another story that there was a group of boys, including her sons, running around Richmond and they brought him home with them.

The (recorded) history of that child ends in 1865. I elevated him to a grown-up. I wanted it to feel to her like a child had returned. (All four of her sons had died young.) He had always wanted to know his story, so different from hers in that she had benefited from slavery her whole life.

Varina was a remarkably strong and independent woman, well-educated and ahead of her time in her thinking about political and social issues. She married Jefferson Davis when she was 18 and he was 37. How would you describe their marriage relationship, with its many moves, the tumultuous time in the country, and the deaths of their four sons at a young age?

There were lots of separations–sometimes because of his work and sometimes because they were not getting along. They quarreled over his will that left her totally dependent on his brother. There were some rocky periods, for sure, but divorce was out of the question.

When Jefferson Davis learned that he had been appointed president of the Confederacy, he and Varina took the news with a sense of dread. Why was that?

He was appointed and inaugurated (as provisional president) in Montgomery, Alabama (on Feb. 18, 1861), and was inaugurated again in Richmond (on Feb. 22, 1862) after he was actually elected to the post (in November 1861).

Varina had expected him to be named the president and didn’t feel like he had the temperament for the job. She told (her friend) Mary Chesnut that he would be president and that “it will be a disaster.” They had just settled back in at their home at David Bend (near Vicksburg) when word came. Both were depressed about it.

Tell me about Varina’s role as the Confederacy’s only first lady, especially considering that she didn’t agree with her husband on everything politically, and this was a job she never asked for.

Varina Davis

She performed a lot of the conventional duties of a first lady, but was constantly criticized by people in Richmond for being too opinionated, too sharp-witted. Many looked on her as being too Western and crude. Mississippi was still a frontier area when she was growing up there, and it bothered some people who thought that she was not as polished.

Other characters in the book reveal much about Varina. Tell me about Mary Chesnut and her relationship with Varina. Also, who is the mysterious character of Laura, who befriended Varina when they were both guests at the health spa in Saratoga Springs?

Many Chesnut and Varina were friends in the real world. They met in Washington when each was 18 and their husbands were members of Congress.

Mary was from South Carolina. She was well educated in Charleston and was known for being smart and quick-witted. Mary’s husband had important positions in the Confederate government (as an aide to the president and a brigadier general in the Confederate Army). The diaries she wrote during the Civil War were later published and they provided a great deal of firsthand information about that period.

For Laura’s character, I pictured someone with lots of problems whose rich parents sent away to get better. At the end of the book, they are trying expensive new medical treatments for her. Also, Varina had lost so many of her own children, and, in Laura, she finds someone to take care of.

The use of mixing wine with morphine, or taking opium or laudanum seemed to be a common practice as a way to relax and forget life’s problems, and we see Varina using it fairly often. How common was this?

You didn’t need a prescription for laudanum (or tincture of opium)–it was the type of thing you could get at traveling medicine shows. It was used for practically anything, especially for women, from mild depression after childbirth, to husbands saying their wives were too high strung or high-spirited. I don’t know if Varina was a big (user), but I do know Mary Chesnut was. I expect some periods of Varina’s life could be explained by her use of it. For example, the way she suddenly left during her husband’s inauguration in Montgomery, with no explanation.

Please tell me how you hope Varina will address your concerns about some of the unrest about race that we still see lingering in our country, with the removal of Confederate statues and the division we continue to hear in the national rhetoric.

I think of historical fiction as a conversation between the present and the past, and Varina Davis’s life offered me a complex entry point into that dialogue. That war and its cause–the ownership of human beings–live so deep in our nation’s history and identity that we still haven’t found a way to reconcile and move forward. And it’s important to remember that most of those monuments didn’t spring up right after 1865, but are largely a product of the Jim Crow South. Their continued presence indicates how much the issues of the Civil War are like the armature inside a sculpture–baked into the framework of our country and our culture.

Do you have other writings in the works at this time, or ideas for your next project?

I’ve got a couple ideas in the works and will decide which one to pursue this summer.

This interview has also been posted on the Clarion-Ledger’s website.

Charles Frazier will be at the Eudora Welty House on Thursday, April 26, at 5:00 to sign and read from Varina, Lemuria’s April 2018 selection for its First Editions Club for Fiction.

Set in Kardos’s native New Jersey, the novel starts with close-up magician Natalie Webb, on the verge of being washed up at 27, almost blinding a smarmy lawyer at a corporate holiday show by throwing a playing card at his eye. It’s a compelling and darkly funny opening, one that sets the tone for the rest of what’s to come: a book that expertly walks the line between breeziness and brutality.

Set in Kardos’s native New Jersey, the novel starts with close-up magician Natalie Webb, on the verge of being washed up at 27, almost blinding a smarmy lawyer at a corporate holiday show by throwing a playing card at his eye. It’s a compelling and darkly funny opening, one that sets the tone for the rest of what’s to come: a book that expertly walks the line between breeziness and brutality. His newest book,

His newest book,

Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale.

Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale. Hal & Mal’s is not one story, but many, and the book sheds a warm and witty light on the background and influences that fed into this cultural outpost in Jackson’s downtown. Of all those vines, family clings the strongest with tendrils in every story of the boys who grew up in Perkinston and Booneville, lost their mother young, and held the love of father, stepmother, brother, grandparents, relatives and friends close.

Hal & Mal’s is not one story, but many, and the book sheds a warm and witty light on the background and influences that fed into this cultural outpost in Jackson’s downtown. Of all those vines, family clings the strongest with tendrils in every story of the boys who grew up in Perkinston and Booneville, lost their mother young, and held the love of father, stepmother, brother, grandparents, relatives and friends close. After nearly two decades, award-winning author and screenwriter Chris Offutt of Oxford has released his long-awaited next novel–and this time it is definitive Southern Gothic, as he lays out the story of

After nearly two decades, award-winning author and screenwriter Chris Offutt of Oxford has released his long-awaited next novel–and this time it is definitive Southern Gothic, as he lays out the story of

In a memoir about his duties with the patrol,

In a memoir about his duties with the patrol,

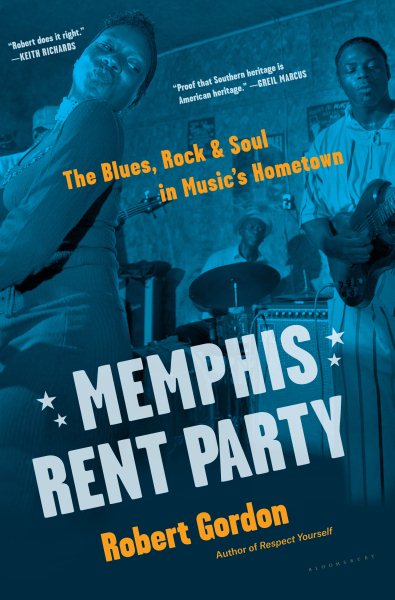

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown