Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (June 10)

Author and journalist Andrew Lawler admits that, from the beginning, he was warned.

Because he had grown up immersed in the story of the lost colony of Roanoke, he expected immunity to the possibility he would get “sucked in,” as a friend put it, to the mystery of what happened to the 115 men, women, and children who landed on Roanoke Island off the coast of what is now North Carolina, in 1587.

Although the settlers were on a mission to establish the first English colony in the New World, they disappeared without a trace while their leader was away on a six-month resupply trip that had stretched into three years. They left only one clue–a “secret token” carved on a tree.

Although the settlers were on a mission to establish the first English colony in the New World, they disappeared without a trace while their leader was away on a six-month resupply trip that had stretched into three years. They left only one clue–a “secret token” carved on a tree.

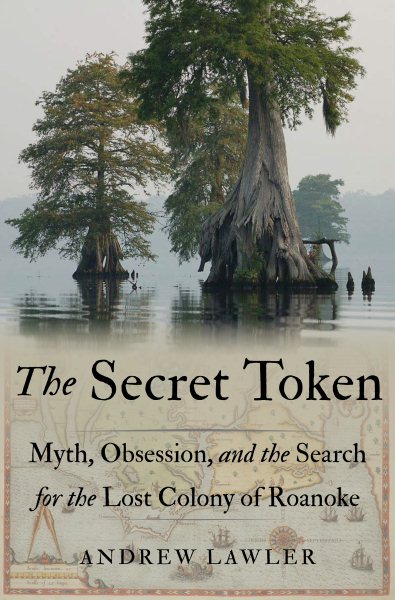

The question of their fate still haunts historians and archaeologists, and Lawler’s own literal journey to examine the ominous expedition resulted in his new book, The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke. What he found, he concludes, offers fresh understanding as to why this mystery is relevant in today’s America.

Lawler is also the author of Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? and is a contributing writer for Science magazine and a contributing editor for Archaeology magazine. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, and other publications.

When did you first develop an interest in the lost colony of Roanoke?

Let’s just say that I had no choice. As a child growing up in southeastern Virginia, not far from Jamestown, there was no escaping history. Figures like John Smith and Thomas Jefferson were regularly mentioned at the dinner table.

On our annual beach trip, my family went to the Outer Banks of North Carolina. This was back in the days when the only nightly entertainment was bingo and a dance hall. The third option was to see The Lost Colony, the three-plus-hour outdoor drama in the buggy woods of nearby Roanoke Island. We sat on hard wooden benches amid the mosquitoes as the organ blared, Indians danced, and sweating English soldiers marched around in breastplates.

It is one of the longest-running plays in American history, and it certainly seemed never-ending to me as a child. Written in the 1930s and performed ever since, it told teh story of the three voyages to the Outer Banks by the English in the 1580s, culminating in the arrival of the final group that today we call the “Lost Colonists.”

There was just enough action to keep a kid interested–plenty of sword fights, fireworks, and firearms going off. But what really fascinated me was the end, when all the settlers go marching off into the woods, hungry and ragged but singing bravely. Then it was our turn, as the audience filed out down the dark path to the parking lot. This was the very place where the Roanoke colonists vanished, and when I was small, that visceral quality of getting lost here struck me with terror. I was relieved to crawl into the back of the station wagon.

As a teenager, fascination replaced the terror. I devoured everything I could find about the colony, reading first-hand accounts and poring over John White’s beautiful watercolors of the Native Americans. But since there was no new evidence to solve the mystery, there seemed nothing fresh to say. Then a few years ago I ran into a British archaeologist while covering a conference at (The University of) Oxford for a magazine. When he told me that he was digging on Hatteras Island, I knew immediately what he was after. Then I found out another team was hard at work digging at another site where the colonists may have gone. Finally, there were new clues emerging. It was a chance to see a childhood mystery solved. Once again, I was hooked.

It seems, from some things mentioned in your book, that you took somewhat of a literary risk by writing The Secret Token. Did you ever doubt that you were doing the right thing?

Andrew Lawler

At first, I was plain embarrassed. I’d spent more than a decade covering the devastating cultural heritage tragedy still unfolding in the Middle East–the looting of the Iraq Museum, the Taliban efforts to wreck Afghan statues, and the ongoing destruction of ancient sites in Syria. Writing about a few dead Elizabethans seemed almost absurdly irrelevant. And when I brought up the “Lost Colony,” more than one historian smirked. It was all so wrapped up in cheesy pop culture, and most serious academics gave the entire episode a wide berth.

I thought I would just do a quick online story, but then it turned into a full-fledged magazine story. Then I realized that I was amassing so much material that it had to be a book. I’ve learned that when I have sinking feeling in my gut–the “Oh, no, anything but that” feeling, then I have hit on the story that I have to tell.

There are many theories about the fate of the English colonists who were never found. In your opinion, which one is the most outlandish? Most reasonable?

My personal favorite is that the colonists turned into zombies that are still out there in those spooky Roanoke woods. Alien abduction is another. Of course, there are can’t -be-proven theories–that they sailed away on their small ship and drowned. We know now that a severe drought afflicted that time period, and some argued they starved to death. But when you look at later “lost” Europeans, most of them simply deserted to or were captured by Native Americans. As Benjamin Franklin noted, few wanted to return, even if they were taken by force. This was what I call colonial America’s dirty little secret.

So, it seems pretty obvious that if you are hungry and don’t know how to survive in a strange environment, you will find people who know what they are doing–and in this case, that was the local Native American population. Eastern North Carolina was filled with thousands of people who thrived in villages and towns, planting crops while also gathering plants and hunting animals. The English didn’t land in a wilderness. So, most historians who have studied the Roanoke voyages agree they did what most of us likely would do–hang out with the people who could make sure you were fed, kept warm, and protected from enemies. In return, they had skills the Indians wanted, like how to make metal implements.

You traveled to Portugal to research the life of the pilot Fernandes. What was the most important thing you learned on this trip, and did you travel to other places for research?

This was a crazy effort to track down a bizarre rumor. The private papers of the Roanoke navigator Simao Fernandes were said to have surfaced in Portugal. A couple of American historians had tried and failed to verify the story, which promised to rewrite our entire understanding of the voyages, and I couldn’t resist the challenge. After running around Portugal and Spain pursuing every lead, I came up empty-handed. But as was always the case with following what seemed a dead end in this tale, I stumbled into something unexpected and important.

In this case, I found that Fernandes was not the villain he was portrayed to be, and that, in fact, he was quite possibly the real mind behind the entire project. He knew and understood the emerging global economy better than any Englishman of his day. And since Roanoke laid the foundation for Jamestown and all other English efforts that followed, you could say this obscure Portuguese pirate played a central role in launching both the United States and the British Empire.

You wrote that “In a nation fractured by views on race, gender, and immigration, we are still struggling with what it means to be American.” Explain in what ways gender issues are tied to this story.

A woman writer named Eliza Lanesford Cushing coined the term “Lost Colony” and made Virginia Dare a folk sensation in the 1830s. This was a moment when women’s magazines first appeared, and women writers like Cushing finally had outlets for their work. But American history at that time was exclusively about men, Betsy Ross being the exception proving the rule. Women were portrayed as bit players in Jamestown and Plymouth when they appeared at all. Men got the credit for “taming the wilderness.”

All we know about Virginia Dare was her name and when she was born and baptized, but her status as the first English child born in the Americas gave women a stake in the origin story of the United States. The Virginia Dare stories, though almost wholly fabricated, became wildly popular among women in the 19th century. They finally could see themselves in the drama that led to the nation’s founding.

Is there any hard evidence that the English settlers “chose” to adopt the Native American lifestyle, as some have suggested?

If they wanted to live, the settlers had to become Native Americans. When Europeans first arrived on the North American coast, they didn’t have the skills to survive, even when their ships regularly brought supplies. They depended on trading their goods with the locals for food. Without the indigenous peoples, all the early European settlements almost certainly would have failed.

Finding hard evidence for Lost Colony assimilation, however, is tricky. If they became Native American, would Jamestown settlers 20 years later have recognized them? Probably not. There certainly are hints that when John White came back in 1590, three years after leaving for England to get supplies, he was watched by people–perhaps including assimilated Lost Colonists who dreaded boarding a cramped and stinking ship for a long passage back to gloomy and plague-ridden London. But I pieced together circumstantial bits of evidence to make a what I think is a compelling case that the Elizabethans became Algonquian speakers–and that their most likely descendants ended up in a most surprising place.

Why is the story of the Lost Colony relevant today?

There are moments in the life of our nation when what it means to be American becomes hotly contested. This was true in the 1830s, when an influx of German and Irish shook up the majority Anglo-Americans. Certainly, during and after the Civil War we differed on whether African Americans could or should be full citizens.

A century ago, we decided women should be able to vote, though at the same time we didn’t generally considers of Italians or Jews to be “white.” In each of these periods, the story of the Lost Colony served as a fable reflecting these tensions. So it is today, with groups like Vdare Foundation warning whites about the dangers of being outnumbered by non-European immigrants. So, I can’t think of a more relevant story in today’s climate.

Do you have ideas in the works for an upcoming book?

I’m drawn to the ancient tales that seem to define how we see the world today. Right now, I’m spending time in the Middle East exploring the source of religious tension there. Few places on Earth are so driven by old stories, particularly those that many see as God-given.

Andrew Lawler will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, June 13, to sign and read from The Secret Token. The Secret Token is Lemuria’s July 2018 selection for our First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

The plots of White’s stories, when summarized, sound like the standard fare of short literary fiction. Lovers endure a strained vacation in the touristy Tennessee mountains; an angry father stares down his impending death; a young boy makes a brave choice that results in an uncomfortable coming of age. But in White’s hands, these small personal dramas are spiked with edgy hilarity.

The plots of White’s stories, when summarized, sound like the standard fare of short literary fiction. Lovers endure a strained vacation in the touristy Tennessee mountains; an angry father stares down his impending death; a young boy makes a brave choice that results in an uncomfortable coming of age. But in White’s hands, these small personal dramas are spiked with edgy hilarity.

The Jazz Pilgrimage of Gerald Wilson

The Jazz Pilgrimage of Gerald Wilson His new novel chronicles the path of Asher Sharp, a Tennessee minister whose struggle with his brother’s “coming out” finally forces a decision for the small-town preacher that results in chaotic consequences for his congregation and his marriage–and threatens his relationship with son. Sharp spontaneously decides to head to Key West, the southernmost point in the country, to search for his brother and seek a long-awaited resolution.

His new novel chronicles the path of Asher Sharp, a Tennessee minister whose struggle with his brother’s “coming out” finally forces a decision for the small-town preacher that results in chaotic consequences for his congregation and his marriage–and threatens his relationship with son. Sharp spontaneously decides to head to Key West, the southernmost point in the country, to search for his brother and seek a long-awaited resolution.

Although the settlers were on a mission to establish the first English colony in the New World, they disappeared without a trace while their leader was away on a six-month resupply trip that had stretched into three years. They left only one clue–a “secret token” carved on a tree.

Although the settlers were on a mission to establish the first English colony in the New World, they disappeared without a trace while their leader was away on a six-month resupply trip that had stretched into three years. They left only one clue–a “secret token” carved on a tree.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events. In his newest title,

In his newest title,

His most recent work,

His most recent work,

His writings have won numerous awards and honors including the Booker Prize, the Prix Médicis, and the Irish Times International Fiction Prize. With such a superlative record, expectations naturally run high, and his latest novel,

His writings have won numerous awards and honors including the Booker Prize, the Prix Médicis, and the Irish Times International Fiction Prize. With such a superlative record, expectations naturally run high, and his latest novel,  Few books could justifiably be called game-changers, but Brother to a Dragonfly was one for me when I first read it in college. It covers his formative years through the height of the civil rights movement as he became, in his words, a self-satisfied white southern liberal. You meet those, like his grandfather, the son of a Confederate soldier, who introduced him to the idea of nonviolence. From the first sentence to the last, you get to know Joe, the titular protagonist who was troubled but was ever the supportive critic, constantly pushing Will to truly evaluate his motives within the movement.

Few books could justifiably be called game-changers, but Brother to a Dragonfly was one for me when I first read it in college. It covers his formative years through the height of the civil rights movement as he became, in his words, a self-satisfied white southern liberal. You meet those, like his grandfather, the son of a Confederate soldier, who introduced him to the idea of nonviolence. From the first sentence to the last, you get to know Joe, the titular protagonist who was troubled but was ever the supportive critic, constantly pushing Will to truly evaluate his motives within the movement. Forty Acres and a Goat is a companion memoir that develops on the lessons from Brother to a Dragonfly and extends them in time as he returned to a rural home, this time to a farm outside of Nashville, Tennessee. We meet Jackson, the goat and gatekeeper to the draft-dodgers and other non-conformists who visited or found refuge in the Campbells’ company.

Forty Acres and a Goat is a companion memoir that develops on the lessons from Brother to a Dragonfly and extends them in time as he returned to a rural home, this time to a farm outside of Nashville, Tennessee. We meet Jackson, the goat and gatekeeper to the draft-dodgers and other non-conformists who visited or found refuge in the Campbells’ company. In his daring second novel,

In his daring second novel,