Margaret Bradham Thornton’s sophomore novel takes the age-old choice between clinging to the familiarity of solitude versus daring to reach for love at the risk of a broken heart and examines it at a deeper level in A Theory of Love–a romantic story that is both unique and familiar at its core.

The chance meeting of British journalist Helen Gibbs and French-American financier Christopher Delavaux on a Mexican beach leads to a relationship and a marriage that would become threatened by ambition and time apart–and ultimately, a difficult choice that must be made for

The chance meeting of British journalist Helen Gibbs and French-American financier Christopher Delavaux on a Mexican beach leads to a relationship and a marriage that would become threatened by ambition and time apart–and ultimately, a difficult choice that must be made for

their future together.

Thornton is the author of the novel Charleston and the editor of Notebooks, a 10-year writing project that saw her compiling and editing the extensive collection of the personal journals of Tennessee Williams. For her efforts on this project, which she said “represented an important record, both emotional and creative, of one of America’s most important writers,” she received the Bronze ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year Award in autobiography/memoir and the C. Hugh Holman Prize for the best volume of Southern literary scholarship published in 2006, given by the Society for the Study of Southern Literature.

Margaret Bradham Thornton

A native of Charleston, she is a graduate of Princeton University, where she majored in English. Now a Florida resident, Thornton is no stranger to Mississippi.

“In my early teens, I came to Jackson and played the Southern Tennis Championships,” she said.

“At various times over the past 15 summers, I have been back to Jackson for tournaments with my three sons–one of whom is a published novelist–who play or have played competitive tennis. I have just returned from Dublin where my daughter competed in the much-loved Dublin Horse Show where the Irish combine their love of horses with their love of books. One of the jumps in the Grand Prix Competition was a five-and-a-half-foot wall of books. I am very happy to report that my daughter cleared it!”

A Theory of Love offers a depth beyond the plot of most “love stories.” It was the busyness of life–the travel, the time pressure, the distance–that defined the relationship of main characters Helen and Christopher, and it requires a bit of thought on the reader’s part to imagine oneself in their shoes–his side and her side. What was your inspiration for this unique book?

Broadly speaking, Tennessee Williams and, more specifically, a memoir of a circus performer.

Tennessee Williams wrote about longing, rarely about love. For example, in The Glass Menagerie, Laura waits for gentlemen callers who never come; in A Streetcar Named Desire, Blanche waits on a decaying plantation for a man to rescue her; and in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Maggie tells Brick that if she thought he would never make love to her again, she would go into the kitchen and get the biggest knife and stick it straight through her heart. Having spent 10 years working on Tennessee Williams, I wanted to move past longing into the territory of love.

Five years ago, I came across a 19th century memoir of a circus performer, Ins and Outs of Circus Life or Forty-Two Years Travel of John H. Glenroy, Bareback Rider, through United States, Canada, South America and Cuba. John H. Glenroy was an orphan, who at age 7 joined the circus. When he retired, he dictated his memoir. Far from telling a life of adventure, he gave a flat, unemotional accounting of all the places he had performed along with the names of all the performers in each circus.

Memory had clearly been a companion to him. And it made me curious: if you’d had love withheld from you as a child, who would you be as an adult? What could be expected of you? Despite living two centuries apart, the circus performer became the inspiration for one of my main characters, and I thought a circus would be a good metaphor for the world of finance. I settled on short chapters with changing locations to give a sense of speed and dislocation.

Please explain the “entanglement theory” and how it expresses this love story.

Simply put, in theoretical physics, two particles that have been close can be separated by millions of miles or even light years and still remain connected. What happens to one, instantaneously happens to the other. Entangled particles transcend space. I thought this was an intriguing concept to explore as a metaphor for love. I think it certainly applies to maternal or paternal love. The question I wanted to ask in this novel was does it hold for romantic love.

What was it that attracted Christopher and Helen to each other in the beginning?

Initially, they are both intrigued by each other’s independence. Christopher notices Helen getting out of a taxi, and he is curious to know why she has come alone to Bermeja. He is further intrigued by her sense of purpose and bemused by his inability to “derail” her from her work. Her article on words reveals her interest in other cultures and a certain fearlessness about crossing borders, exploring new terrain, both literally and metaphorically, and this aspect of her certainly appeals to him.

Helen is curious to know more about Christopher who is staying in a remote place by himself–she is, after all, a journalist. Her choice of words shows that she is drawn to illusive concepts that have both intensity and peace and these words could be used to describe aspects of Christopher. Christopher’s ability to embody his favorite word, sprezzatura, to make whatever he does look as if it is without effort or thought–especially when he is flirting with her–appeals to Helen and keeps her off balance at the beginning of their relationship.

I was struck by the fact that Christopher, like Helen, had a favorite word! Do you have a favorite word?

I didn’t until I wrote this book, but I would go with neverness, partly because of how I first learned about it; partly because it is an orphaned word and I have been thinking about orphans; and partly because it is beautiful. My eldest son, a writer, sent me an excerpt from a Paris Review interview with Jorge Luis Borges who described this word, invented by Bishop Wilkins in the 17th century, as “a beautiful word, a word that’s a poem in itself, full of hopelessness, sadness, and despair.” He said he could not understand why “the poets left it lying about and never used it.”

Despite the constant travel to romantic and exotic places, there is a very “everyday” feeling about this book, as we get glimpses of the “ordinary” about Helen and Christopher, despite the pace of their lives. That is somewhat of a luxury among novelists, who may present frequent moments of “drama” to move the plot along . . . . but this story doesn’t feel rushed. Explain how you approached the pace of this book, as it pertains to their relationship.

This book was an explanation of the question, “What does it mean to love someone?”, and for that question, plot did not have a strong place. Novels that helped me understand how to think about structuring this story include Kate Chopin’s The Awakening; Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris; Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky; and James Salter’s Light Years and Solo Faces.

In The Awakening, there is that powerful scene between Edna and Robert when he waits with her one evening. They are both deeply attracted to one another, but neither can act upon their passion, and he waits with her for her husband to return. I thought it was an extraordinary scene–all the more so because so little is said. I knew I wanted to write that kind of scene in my novel at the end when Helen is sitting on a swing in Bermeja.

Your writing style is very fluid, and it makes me wonder how, as a Charleston native, you were influenced by favorite writers. Who did (and do) you admire as writers?

I don’t have favorites, but I do have mileposts.

Growing up in Charleston, books, for me, were passports. Initially I bypassed Southern writers, as I felt I knew a lot about the South and wanted to learn about other parts of the world. I’m happy to say, since then, I’ve reversed direction and put my arms around many of the great Southern writers–Faulkner, Welty, O’Connor, Percy, Williams, Capote, McCarthy, the list goes on.

In college, I read all of Henry James and was struck by the subtlety of his language and structure of his novels. I was also impressed how Virginia Woolf inventively used form to serve her meaning.

Another milepost was when I read Edisto by Padgett Powell when it was first published. The narrator, Simons Manigault, says, “We drove half that night, up Highway 17, watching all the flintzy old motels with names like And-Gene Motel.” I had passed the And-Gene Motel which was halfway between Charleston and the Edisto River hundreds of times, and I remember thinking–you can do that in a novel?

While working on Tennessee Williams, I indirectly discovered the kind of reader I wanted to be. Williams tried to write a play on Vincent van Gogh and one of the books he read was Letters to an Artist: From Vincent van Gogh to Anton Ridder van Rappard 1881-1885. Van Gogh collected the prints published by two London newspapers, and in his letters to van Rappard, he generously praised the work of many of the artists. For example, he wrote, “Pinwell draws two women in black in a dark room in the simplest possible composition in which he has put a serious sentiment that I can only compare to the full song of the nightingale on a spring night.”

In a letter to his brother Theo, van Gogh wrote, “Reading books is like looking at paintings: without doubting, without hesitating, with self-assurance, one must find beautiful that which is beautiful.” That sentiment struck me: as a writer, it felt like the right way to read. So, in that spirit, I try to read as broadly as possible.

Are plans in the works for another novel? If so, can you share something about it with us?

I have been thinking about the idea of beauty and evil. In my research on foundlings for A Theory of Love, I visited the Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence, and there I learned that an early benefactor had donated a large collection of great paintings to the orphans because he felt that everyone should grow up with beauty. In Book Nine of Paradise Lost, Satan is so struck by the beauty and grace of Eve that he is temporarily disarmed of hatred and envy and revenge.

I am in the early stages of a novel that considers whether or not there is a relationship between evil and beauty, and if so, what is it.

If I’ve learned anything from Tennessee Williams, it is to write about what intrigues or perplexes or moves you–or in his words–to write “a picture of your own heart” and to convince yourself it is easy to do. “Don’t maul, don’t suffer, don’t groan–till the first draft is finished. Then Calvary–but not till then. Doubt–and be lost–until the first draft is finished.”

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

James A. McLaughlin’s

James A. McLaughlin’s  Too often it takes years, but right can triumph over wrong. In

Too often it takes years, but right can triumph over wrong. In  Mississippi’s Julia Reed, a columnist and author of six previous books, has blessed her fans with yet another salute to the South, this time with

Mississippi’s Julia Reed, a columnist and author of six previous books, has blessed her fans with yet another salute to the South, this time with

Saturday, August 18, will be full of panels, many often occurring simultaneously. Nestled between discussions that focus on authors or themes or genre books is a panel that features a book publisher. Often neglected at this sort of event, the Mississippi Book Festival has chosen each year to highlight a different press that is bringing great books to the world. Billed as,“an inside look at the ups and downs of publishing and the relationship between a national literary publisher and two of its award-winning authors,” this year’s publishers panel will host

Saturday, August 18, will be full of panels, many often occurring simultaneously. Nestled between discussions that focus on authors or themes or genre books is a panel that features a book publisher. Often neglected at this sort of event, the Mississippi Book Festival has chosen each year to highlight a different press that is bringing great books to the world. Billed as,“an inside look at the ups and downs of publishing and the relationship between a national literary publisher and two of its award-winning authors,” this year’s publishers panel will host

Gary Krist’s fascinating account of the history of Los Angeles during the first three decades of the 20th century puts a highly personal face on the mage-city’s early days through the almost unbelievable stories of three of its most interesting and important influencers in

Gary Krist’s fascinating account of the history of Los Angeles during the first three decades of the 20th century puts a highly personal face on the mage-city’s early days through the almost unbelievable stories of three of its most interesting and important influencers in

In the 1950s, the Beats adopted the form to publish poetry, most famously “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg and issued by Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights books in San Francisco. The Pocket Poet Series introduced avant-garde poetry to the masses and is still in print today. Broadside Press in Detroit supported the writers of the civil rights movement, publishing Margaret Walker’s “

In the 1950s, the Beats adopted the form to publish poetry, most famously “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg and issued by Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights books in San Francisco. The Pocket Poet Series introduced avant-garde poetry to the masses and is still in print today. Broadside Press in Detroit supported the writers of the civil rights movement, publishing Margaret Walker’s “ John Updike’s “The Women Who Got Away” (William B. Ewert, 1998) is an example of an embellished chapbook illustrated with woodcuts by Barry Moser. “Gwinlan’s Harp” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Lord John Press, 1981) and “

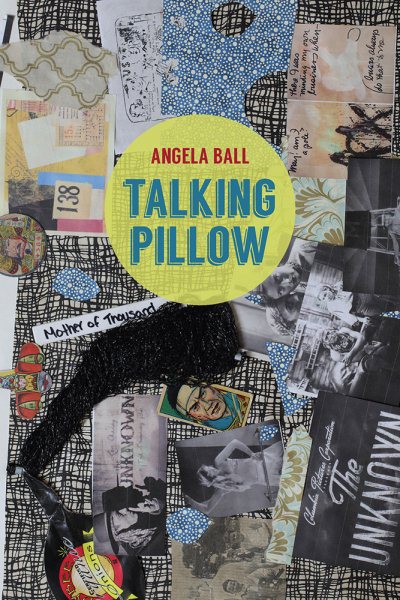

John Updike’s “The Women Who Got Away” (William B. Ewert, 1998) is an example of an embellished chapbook illustrated with woodcuts by Barry Moser. “Gwinlan’s Harp” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Lord John Press, 1981) and “ Underscored by the sudden death of Ball’s long-time partner, each poem in

Underscored by the sudden death of Ball’s long-time partner, each poem in