Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (September 3)

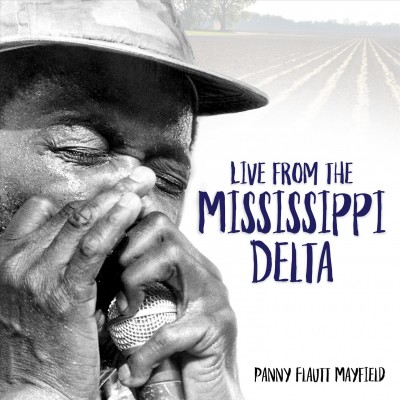

Panny Flautt Mayfield

As an award-winning journalist and lifelong Mississippi Delta native, Panny Mayfield of Tutwiler has captured decades of blues and gospel music history through her camera lens–and her debut book, Live From the Mississippi Delta (University Press of Mississippi), tells that unique story through her unique, up-close perspective.

The recipient of more than 30 awards granted by the Mississippi Press Association, the Associated Press, the Mississippi Film Commission, and the College Public Relations Association of Mississippi, Mayfield’s work has been exhibited in museums across the U.S. and in Europe.

In Live from the Mississippi Delta, she shares more than 200 photos of Delta performers and their musicians, fans, friends, and families, taken at churches, clubs, festivals, and iconic juke joints, alongside her own detailed accounts of the lives and fortunes of dozens of familiar blues and gospel performers–including those who were Delta natives as well as international superstars who traveled from around the world to pay homage to the legends who influenced their own music.

Tell me about your childhood in Tutwiler and how you came to be a noted Mississippi Delta photographer.

Growing up in Tutwiler, a busy railroad town south of Clarksdale, I enjoyed small town life watching Randolph Scott movies at the Tutrovansum Theatre (a [portmanteau] for the Mississippi communities it served: Tutwiler, Rome, Vance, and Sumner), playing kick the can, and catching lightning bugs in Mason jars. I was aware of places like Lula Mae’s Sunrise Cafe where infectious music spilled out on the street, but it was totally off limits to me until I became an adult.

Photography fascinated me at about the age of 12. I began taking pictures and writing about cross-country family trips, became newspaper editor in high school and at Ole Miss, and began a lifelong career as a journalist and photographer.

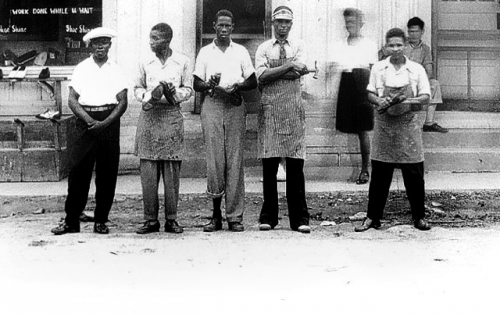

I began taking blues photographs in the late 70s when Sid Graves founded Clarksdale’s Delta Blues Museum. Bluesman Wesley Jefferson needed a portfolio and asked me to photograph his Southern Soul Band playing at Margaret’s Blue Diamond Blues Club on the railroad tracks in Clarksdale’s New World District. I organized a folder for James “Super Chikan” Johnson who needed to get serious booking gigs.

It was Mae, Michael James’ lady, who began teaching me to dance to blues music in her kitchen. Decades later, I’m still working on my dancing and sharing the drama of the passionate music that is the Mississippi Delta blues.

After a career as a newspaper journalist and a public relations director for a community college, Live from the Mississippi Delta is your first book. How did this book come about?

My careers with newspapers, magazines, and Coahoma Community College were incredibly busy. Although I considered a book somwhere down the line, I was busy making a living and meeting ever-present deadlines until I retired in 2013. I was encouraged to put a book together by Molly Porter of Vermont, who scanned many of my photographs. Initially it was a book of photographs until Craig Gill, University Press of Mississippi’s director, urged me to include stories and text about many of the images, musicians, and events. The book itself is half text, half photos.

Explain what the blues, as a music genre, means to the Mississippi Delta.

I’m not sure if I can explain how much blues means to the Mississippi Delta. They are inseparable, conjoined. When the eminent folklorist and musician Alan Lomax returned to Clarksdale in 1994, he emphasized the similar, unique qualities of Coahoma County blues to the original rhythmic music of Senegal in Africa, and he encouraged a cultural revival in the Delta.

You helped launch Clarksdale’s Sunflower River Blues and Gospel Festival in 1988. Are you still involved in it?

Jim O’Neal, co-founder of Living Blues magazine, and research director of Mississippi’s Blues Trail, co-founded the Sunflower River Blues Association, and he was here last month for the festival’s 30th anniversary. In 1988, we were considered an avant-garde bunch, but we followed Jim’s lead, staging a free music festival showcasing local musicians as well as well-known artists.

I asked Jim at that time what he thought of today’s Sunflower (festival), and he said he was glad it continued to be a unique, grassroots event where people felt comfortable and at home. This year, we had people from New Zealand, Italy, Germany, Paris, and Bangkok, Thailand.

I’m still publicist for the festival and I love our multiracial, diverse membership. I believe this contributes to the success of our festival.

Your book includes sections on Delta landscapes, “homegrown” and international blues musicians, Delta festivals, juke joints, and more, and your career as a photographer has given you front-row access to scores of musically influential events and people. What have you enjoyed the most and what have you found to be the most challenging?

My book begins with my own beginning in Tutwiler–also the birthplace of blues. it’s where W.C. Handy first head a guitar being played with a kitchen knife in 1903, and where the charismatic Robert Plant paid tribute in 2009 to the music that influenced his own phenomenal career.

I have been one incredibly person to have this background and to fine-tune it in Clarksdale, center of the blues universe. My books “homegrown icons”–radio broadcaster Early Wright, who invited me to his birthday dinners every February 10; and barber Wade Walton with his stuffed monkey Flukie–are just as important to me as international celebrities ZZ Top, James Brown, and Garth Brooks.

Describe Clarksdale’s association with its “sister city,” Notodden, Norway.

Clarksdale’s sister city relationship with Notodden, Norway, began in 1996 with initial visits by Norwegian journalists, musicians, and then city offiicials interested in researching blues history to enhance their own international festival and its connection with the Sunflower River Blues and Gospel Festival.

Norwegian officials dined on catfish; were entertained at the Rivermount Lounge, a local club favored by Little Milton, Ike Turner, and Bobby Rush; and were taken to a Marvin Sease blues show at the City Auditorium that went on until 2 a.m. The next morning, they attended a service at Friendship Missionary Baptist Church at Friar’s Point, where members lined up to shake every Norwegian’s hand. Overnight, we became “cousins,” and exchanges between the two cities have flourished.

Tell me about the cover of your book.

I get emotional about the cover of my book. The musician–Arthneice Jones–is one of the most talented and articulate bluesmen I have known. A harmonica master and singer/songwriter, Arthneice was leader of The Stone Gas Band–a talented and popular bunch who played all over north Mississippi and Memphis before his untimely death. A musician who worked in concrete, Arthneice intrigued, charmed, and connected intimately with Sunflower acoustic audiences each summer with sidewalk philosophy mixed with music.

I get emotional about the cover of my book. The musician–Arthneice Jones–is one of the most talented and articulate bluesmen I have known. A harmonica master and singer/songwriter, Arthneice was leader of The Stone Gas Band–a talented and popular bunch who played all over north Mississippi and Memphis before his untimely death. A musician who worked in concrete, Arthneice intrigued, charmed, and connected intimately with Sunflower acoustic audiences each summer with sidewalk philosophy mixed with music.

My initial choice for the book cover was a juke joint scene from Shelby’s Dew Drop Inn. But when University Press of Mississippi emailed, unannounced, the image of Arthneice imposed on raw Delta cotton fields, i cried. It was so perfect.

Do you have any plans for more books?

As a journalist trained to condense news and feature articles into brief, interesting opening lines with zero personal commentary, writing a book was a new experience. Fortunately, Craig Gill and the UPM staff were patient and encouraging. Helpful also were remembrances of my mother’s storytelling traditions.

A future book about 25 years of celebrating America’s great playwright with the Mississippi Delta Tennessee Williams Festival is a possibility.

An artist at heart, Spencer set out in 2003 on a quest to capture a post-9/11 America–to grasp a glimpse of a country of contrasts, fears, and hopes. The resulting book, he says, is “not a documentary or dogmatic statement, but rather an expression of the perception of the ideal.” The images are rendered in what he calls a “stream-of-consciousness perspective,” not “perfect pictures.”

An artist at heart, Spencer set out in 2003 on a quest to capture a post-9/11 America–to grasp a glimpse of a country of contrasts, fears, and hopes. The resulting book, he says, is “not a documentary or dogmatic statement, but rather an expression of the perception of the ideal.” The images are rendered in what he calls a “stream-of-consciousness perspective,” not “perfect pictures.”

Author and journalist Mark Bowden challenges a new generation of readers to question America’s involvement in Vietnam as he examines, with laser precision, the bloody battle for the city of Hue (pronounced “whey”) in his newest release

Author and journalist Mark Bowden challenges a new generation of readers to question America’s involvement in Vietnam as he examines, with laser precision, the bloody battle for the city of Hue (pronounced “whey”) in his newest release

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book,

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book,

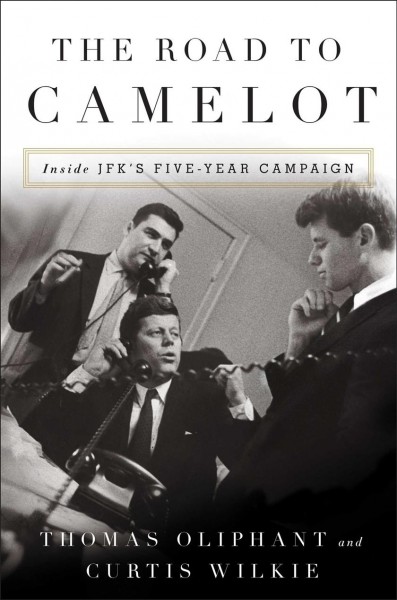

In 2003, I had an idea to write a book about one dramatic afternoon at the 1956 Democratic convention when Kennedy challenged the party establishment and nearly became the vice presidential nominee after Adlai Stevenson asked the delegates to choose his running mate. Even though he lost, Kennedy emerged as a new political star. As a teenager watching the struggle on TV, I had been fascinated. It was the last time any convention has gone past a first ballot.

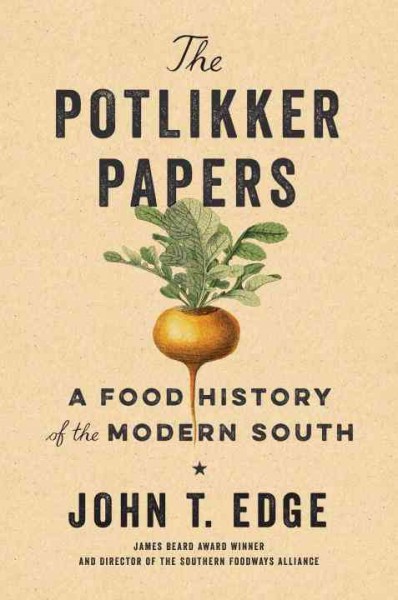

In 2003, I had an idea to write a book about one dramatic afternoon at the 1956 Democratic convention when Kennedy challenged the party establishment and nearly became the vice presidential nominee after Adlai Stevenson asked the delegates to choose his running mate. Even though he lost, Kennedy emerged as a new political star. As a teenager watching the struggle on TV, I had been fascinated. It was the last time any convention has gone past a first ballot. “I wanted to reconcile my profound love of the South with a deep anger that boiled in me when I confronted our peculiar history,” he writes in his newest book,

“I wanted to reconcile my profound love of the South with a deep anger that boiled in me when I confronted our peculiar history,” he writes in his newest book,

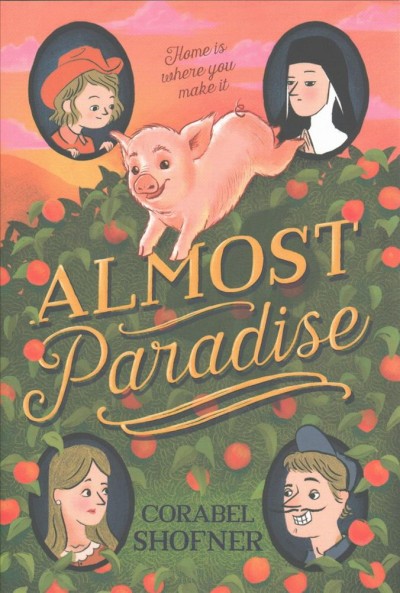

Now in her mid-60s, Shofner is officially beginning her new career as a writer, releasing her debut book,

Now in her mid-60s, Shofner is officially beginning her new career as a writer, releasing her debut book,

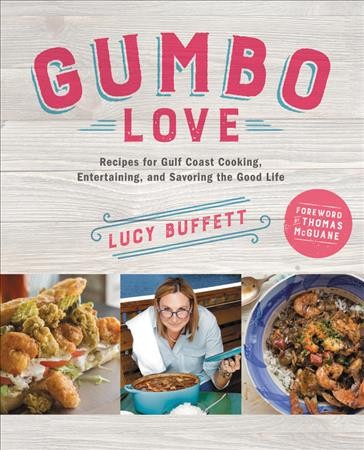

Along with her family, it’s the spirit–and the food–of the Gulf Coast that claim the biggest parts of Lucy Buffett’s heart, and she embraces both in her newest cookbook,

Along with her family, it’s the spirit–and the food–of the Gulf Coast that claim the biggest parts of Lucy Buffett’s heart, and she embraces both in her newest cookbook,

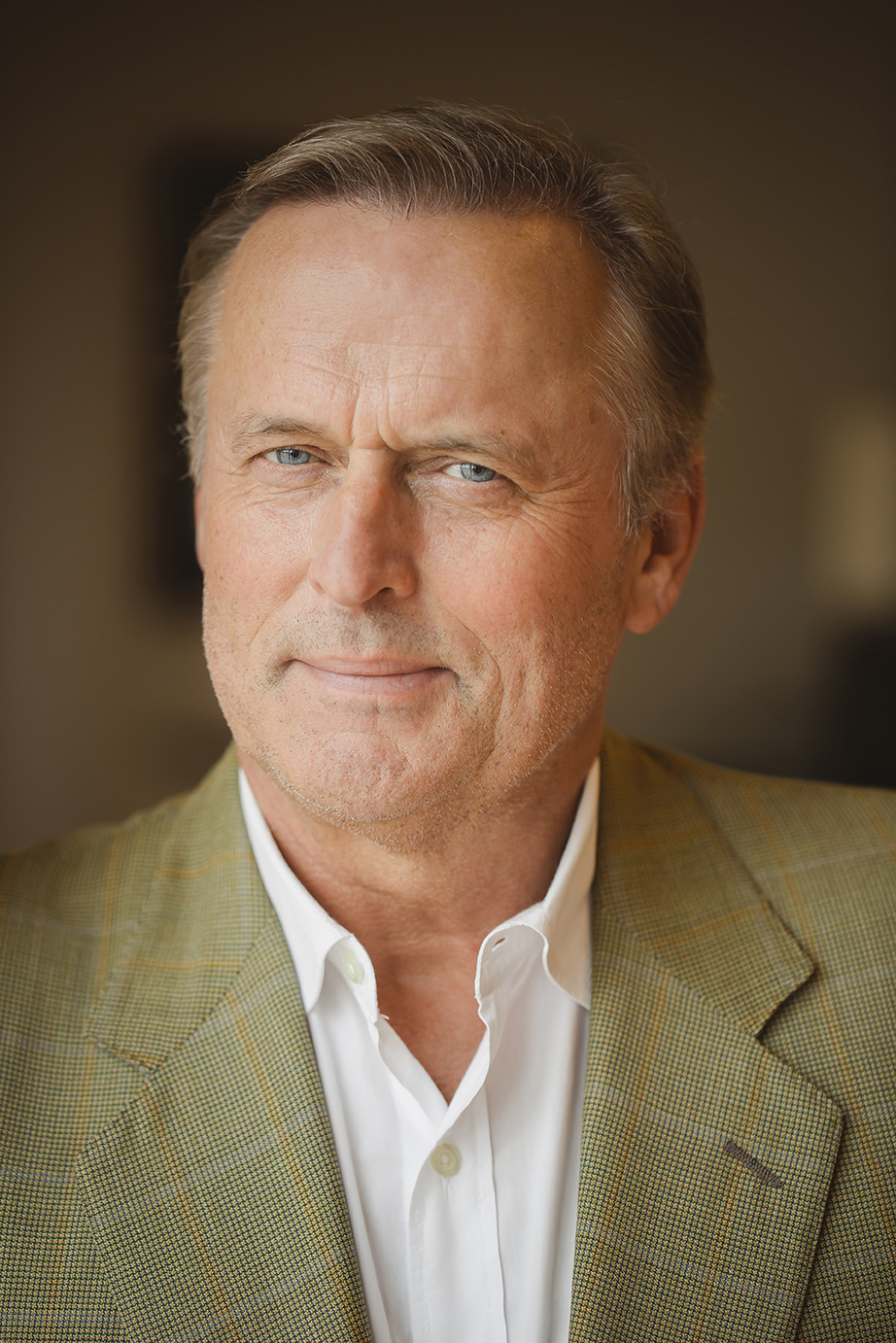

Camino Island is a book about books, booksellers, bookstores, and the rare book business. In this fictional account of the dramatic heist of four original F. Scott Fitzgerald manuscripts from the Princeton University library, most of the story unfolds in the quiet resort town of Santa Rosa, Florida. Main characters Bruce Cable, who owns a popular book store there and Mercer Mann, a hopeful young author, square off in a high-stakes tale of espionage, betrayal, and theft–all within the mysterious world of the rare books trade.

Camino Island is a book about books, booksellers, bookstores, and the rare book business. In this fictional account of the dramatic heist of four original F. Scott Fitzgerald manuscripts from the Princeton University library, most of the story unfolds in the quiet resort town of Santa Rosa, Florida. Main characters Bruce Cable, who owns a popular book store there and Mercer Mann, a hopeful young author, square off in a high-stakes tale of espionage, betrayal, and theft–all within the mysterious world of the rare books trade. Born in Jonesboro, Arkansas, in 1955, Grisham spent most of his childhood in Mississippi, and went on to earn an accounting degree from Mississippi State, and then a law degree from Ole Miss. He was working as an attorney in Southaven and serving as a member of the Mississippi Legislature when he began writing full-time.

Born in Jonesboro, Arkansas, in 1955, Grisham spent most of his childhood in Mississippi, and went on to earn an accounting degree from Mississippi State, and then a law degree from Ole Miss. He was working as an attorney in Southaven and serving as a member of the Mississippi Legislature when he began writing full-time. The last big book tour I did was in 1992, when The Pelican Brief came out. I was living in Oxford at the time, and I knew Willie Morris, Barry Hannah, and Larry Brown. They were always hanging around the bookstore (Square Books), and they talked me into doing a big book tour that turned out to be 35 cities in 34 days. It was not fun and I didn’t think it was productive. I told my publisher I can go back to Oxford and write books or hit the road and do publicity.

The last big book tour I did was in 1992, when The Pelican Brief came out. I was living in Oxford at the time, and I knew Willie Morris, Barry Hannah, and Larry Brown. They were always hanging around the bookstore (Square Books), and they talked me into doing a big book tour that turned out to be 35 cities in 34 days. It was not fun and I didn’t think it was productive. I told my publisher I can go back to Oxford and write books or hit the road and do publicity. Long a master of uniquely inspired short stories, George Saunders’ career as a novelist has just come to life with the release of his long-awaited debut novel. The entire tale unfolds over the course of one night — and almost entirely in a surreal graveyard.

Long a master of uniquely inspired short stories, George Saunders’ career as a novelist has just come to life with the release of his long-awaited debut novel. The entire tale unfolds over the course of one night — and almost entirely in a surreal graveyard. Honestly, trial-and-error. I knew, at the outset, how I didn’t want to tell it: in a sort of standard, third-person realist voice—and I knew this because I’d tried it—ugh! I am always trying to steer toward the fun, or what feels truthful and uncommon. So, all of the book’s odd elements came out of that desire.

Honestly, trial-and-error. I knew, at the outset, how I didn’t want to tell it: in a sort of standard, third-person realist voice—and I knew this because I’d tried it—ugh! I am always trying to steer toward the fun, or what feels truthful and uncommon. So, all of the book’s odd elements came out of that desire.