Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 11)

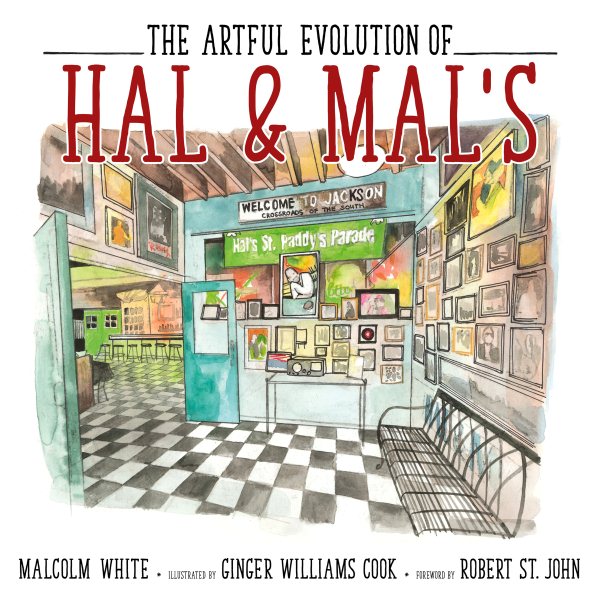

While Malcolm White describes Hal & Mal’s as “a place where art is made, music plays, and folks gather to share community, and celebrate t he very best of Mississippi’s creative spirit,” a good friend puts it another way, calling it simply “the most talked-about upscale honky-tonk in all of Mississippi.”

White’s salute to the more than three decades of success at the iconic establishment he and big brother Hal opened in 1985 is The Artful Evolution of Hal & Mal’s–a 130-page tribute filled with brief, but loaded, character essays of milestones, food profiles, character sketches, ghost stories, musical acts, and an inside look at the chaotic debut of the now-legendary Hal’s St. Paddy’s Day Parade–along with many, many glimpses of heartfelt family history.

White’s salute to the more than three decades of success at the iconic establishment he and big brother Hal opened in 1985 is The Artful Evolution of Hal & Mal’s–a 130-page tribute filled with brief, but loaded, character essays of milestones, food profiles, character sketches, ghost stories, musical acts, and an inside look at the chaotic debut of the now-legendary Hal’s St. Paddy’s Day Parade–along with many, many glimpses of heartfelt family history.

The stories are brought to life in the University Press of Mississippi publication with distinctive watercolors rendered by Jackson native Ginger Williams Cook, who said her mission was to create “a sense of place and connection” to the restaurant’s and family’s “storied past and present.” Describing Cook as a “stunning artist,” White said her contributions to the book “made it the artful project that it is.”

Opening in what Robert St. John describes in the book’s foreword as “a B-location on South Commerce Street inside an old warehouse next to the railroad tracks,” the eatery and arts galleria has thrived, earning itself a spot in the elite category of what St. John calls Jackson’s “classic” restaurants.

It was the childhoods on the Gulf coast, combined with years of working in iconic kitchens in New Orleans, that would bring White and brother Hal to a shared dream of opening their own place someday. That “someday” has become nearly 35 years of family and friends serving up not onky regional food favorites with “a nod toward the Gulf of Mexico,” but a healthy helping of live blues, jazz, and rock music, sprinkled throughout with original works of art.

Malcolm White

White, now on his second stint as executive director of the Mississippi Arts Commission (with a turn at leading the state’s Tourism Division in between), is involved with South Arts, the Mississippi Blues and Country Music Trails and Downtown Jackson Partners.

“I have lived a long and abundant life,” he said, pointing out that he has “managed to amass almost 13 years in the public arena to bookend my 30-plus years in the private sector.”

His previous book, Little Stories: A Collection of Mississippi Photos, was published in 2015.

Tell me about the condition the 1927 warehouse was in when you and Hal leased the property in 1985, and why you chose that unlikely location as the site of the restaurant you had dreamed of opening together.

The building was 95 percent abandoned and dysfunctional. There was no plumbing; it had ancient electrical capacity and was in deplorable condition. It was technically unoccupiable and cost us close to $500,000, in 1980s dollars, over the first couple of years to get it up to code.

We chose downtown Jackson because we believed in Mississippi, our home, and the predication that all centers of population revitalize, and it’s only a question of when, not if. Hal and I used to joke about if we would live to see the vision we had come to pass. I’m still hopeful.

You mention in The Artful Evolution of Hal & Mal’s that “59 percent of hospitality businesses fail within three years of their founding.” What has been the secret to Hal & Mal’s success?

I point out in the introduction of the book that our business philosophy was to include art, culture, and story in the plan and not make it an afterthought; and that we adhered to the sacred axiom that the more money you give, the more you make. And finally, we have always sought inclusion and looked for ways to serve others along the way, like Jeff Good, Robert St. John, Myrlie Evers, and William Winter.

Your book highlights memories of key events, people, and circumstances that have made up the restaurant’s success. Why was it important for you to document the journey of both your family life alongside that of the restaurant that is now an institution in downtown Jackson?

Because the two are inseparable. Our family is the business, and the business tells much of our family story. We actually think we are more than a downtown Jackson institution, we fell we represent a regional, as well as an American enterprise story.

It’s interesting that you’ve been blessed with not only culinary skills, but a love of art and community, a strong entrepreneurial spirit, and the gift of writing. How would you say all of these skills have come to shape your vision for–and the success of–Hal & Mal’s?

The vision for Hal & Mal’s, like the book itself, was shaped over many years of pondering and preparing. Hal and I started talking about this dream when we were in our 20s and didn’t even live in Jackson. We even bought a building in downtown Hattiesburg, the Walnut Street Pharmacy, in the very early 1980s, with the idea of locating there. But fate put us a little further north after I accepted a job in 1979 to come to Jackson. Further, I started collectin ghte Hal & Mal’s decor, furniture and decorations back in the mid-1970s while living and working in both Hattiesburg and New Orleans.

Sadly, your partner and brother Hal White died in 2013, suddenly but only shortly leaving the future of the restaurant in question. Explain what happened that soon made it evident that Hal & Mal’s would survive and continue to thrive.

When Hal died in 2013, I was uncertain that we could or would carry on, but our staff and family rallied and insisted we continue. I had just accepted the job as tourism director and had made a decision that I could no longer work the hours and endure the physical demands of the restaurant and late-night music scene. But here we are, 33 years later, still serving our aunt’s gumbo and Hal’s magical soup concoctions.

You say in the book that Hal & Mal’s is, in some ways, “not just a bar and restaurant, we’re a creative outpost in downtown Jackson,” and it’s obvious that art and music have played important roles in the restaurant’s success. Could you elaborate?

Providing a place for community to gather and break bread is biblical, and paramount to the success of great places. When food and drink, arts and culture are presented side by side in a public house, community is sustained and encouraged. Hal & Mal’s is perhaps the first example of what the creative economy and creative placemaking is all about in Jackson and in Mississippi.

Certainly, there are other examples of this, but in the book and in the programming and continuation of the business, we demonstrate the “how” of such an enterprise and proposition. In many ways, we have shown by example how communities revitalize, sustain, and prosper. If that sounds boastful, then so be it.

At the end of the book you tell readers, “No one knows what the future may hold”–but what would you like to see for Hal & Mal’s going forward? How could it continue to evolve?

We will continue as long as we are able to make a small profit, add to the quality of life and see improvements in our community. We hope to purchase the building in the next few months–after 35 years of paying rent to the state–and begin a renovation of the property.

Since the Hal’s St. Paddy’s Parade and Festival is such a big event and is right around the corner (Saturday), would you also comment on how it has contributed to the evolution of Hal & Mal’s?

Sure. Most people think, mistakenly, that Hal & I started the parade together and that Hal & Mal’s was there in the beginning. Not so. I started the parade–thus the original name, “Mal’s”–in 1983 when I was booking music, producing events, and starting my own company, Malcolm White Productions. I designed the first parade to start at CS’s and end at George Street in a “pub crawl” format. However, as it began to unfold I evolved into thinking more of a traditional parade going downtown, starting at CS’s and ending at George Street.

CS’s dropped out after the first year and George Street, where I worked from 1979 to 1983, became the beginning and ending location. Later, I moved it to the Mississippi State Fairgrounds and finally to Hal & Mal’s in 1986, where it is based today. Hal didn’t join the fun until 1984–though he was living and working in Columbus–when we started the O’Tux Society, our first marching krewe. Hal then moved to Jackson in 1985 when we started Hal & Mal’s.

The parade is an important annual event for both Hal & Mal’s and the city of Jackson as well as teh state. It has an economic impact of $10 million annually on the local economy and enjoys a national reputation as one of the largest and most original St. Paddy’s parades in the country. It is generally associated with Hal & Mal’s and that helps with our brand and our iamge of a place where people meet for arts and culture, and fun and festive occasions.

Malcolm White and Ginger Williams Cook will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, March 14, at 5:00 to sign copies of The Artful Evolution of Hal & Mal’s.

Their new book,

Their new book,

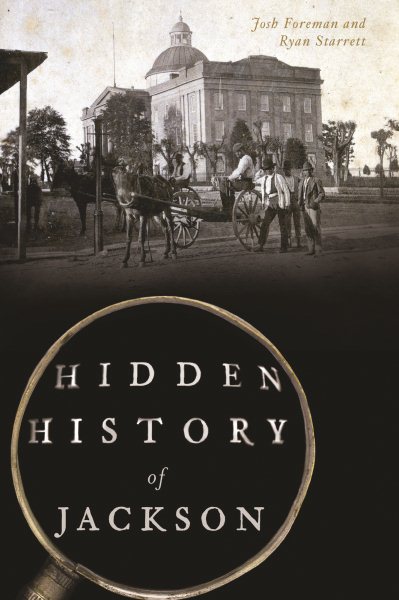

Longtime friends Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett, who both spent childhood years in Jackson, give readers an unexpected and fresh look at their hometown city’s history through 20 mostly never-before-told stories that bring to life the “

Longtime friends Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett, who both spent childhood years in Jackson, give readers an unexpected and fresh look at their hometown city’s history through 20 mostly never-before-told stories that bring to life the “

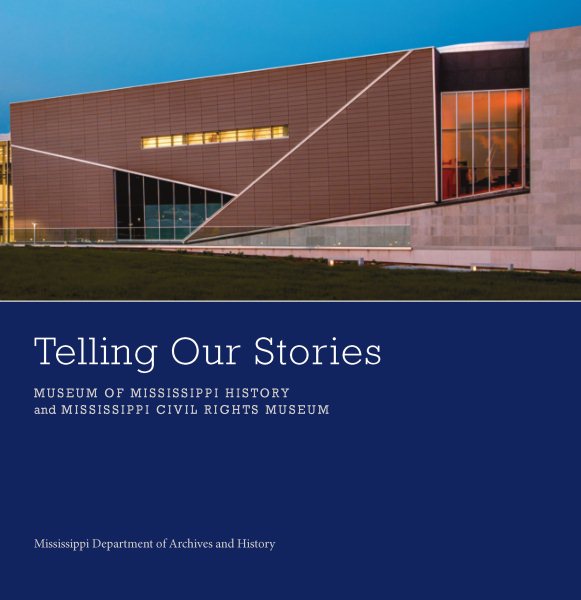

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

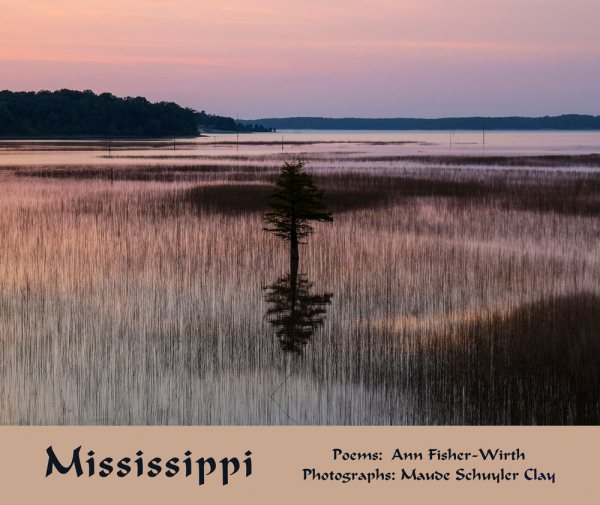

Her newest book, titled

Her newest book, titled

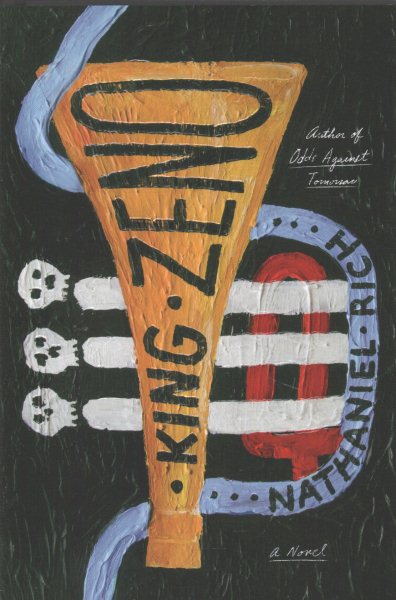

The initial idea grew out of my fascination with two historical events: the series of unsolved ax murders that reached its culmination with a bizarre letter to the Times-Picayune; and the excavation of the Industrial Canal, a hubristic manhandling of the local terrain that has haunted New Orleans ever since.

The initial idea grew out of my fascination with two historical events: the series of unsolved ax murders that reached its culmination with a bizarre letter to the Times-Picayune; and the excavation of the Industrial Canal, a hubristic manhandling of the local terrain that has haunted New Orleans ever since.

I believe each of them is stronger than he initially thinks is the aftermath of that tragedy. Richard is a naturally skilled writer, and those abilities, along with a lifetime of trying to do an honest job as a reporter, eventually re-involve him in life.

I believe each of them is stronger than he initially thinks is the aftermath of that tragedy. Richard is a naturally skilled writer, and those abilities, along with a lifetime of trying to do an honest job as a reporter, eventually re-involve him in life. Jamie Quatro’s debut novel,

Jamie Quatro’s debut novel,

The book, which documents the obvious racial injustice with which the case was handled by local officials, gained national attention because of the eccentric lifestyle of initial suspects Richard Dana and Octavia Dockery, who lived in a decaying antebellum home overrun with crumbling furnishings, pervasive filth–and a pen of goats, among many other animals.

The book, which documents the obvious racial injustice with which the case was handled by local officials, gained national attention because of the eccentric lifestyle of initial suspects Richard Dana and Octavia Dockery, who lived in a decaying antebellum home overrun with crumbling furnishings, pervasive filth–and a pen of goats, among many other animals.

Johnny, a poor, kind, young boy, is forced one day by his cruel grandfather to sell his pet chicken at the market. In doing so, he unexpectedly comes into possession of some magical seeds. From the seeds grow a flower, and upon eating the flower, Johnny is granted the ability to speak with animals. Led by a skunk named Susy, Johnny and all the animals in the land set out on a quest to rescue a stolen prince, and with some luck, perhaps cross paths with a familiar chicken.

Johnny, a poor, kind, young boy, is forced one day by his cruel grandfather to sell his pet chicken at the market. In doing so, he unexpectedly comes into possession of some magical seeds. From the seeds grow a flower, and upon eating the flower, Johnny is granted the ability to speak with animals. Led by a skunk named Susy, Johnny and all the animals in the land set out on a quest to rescue a stolen prince, and with some luck, perhaps cross paths with a familiar chicken. This story began as a piece of oral tradition. It was as a story told out loud, maybe over the course of several nights by an adult to children. I would hope the finished book is used in much the same way. While the language might be difficult for a child under the age of 9 or 10, I believe that children of all ages will be able to appreciate the story–its rhythm, its humor, and its message–especially when told directly to them by a parent, or grandparent, or some other important adult figure in their life.

This story began as a piece of oral tradition. It was as a story told out loud, maybe over the course of several nights by an adult to children. I would hope the finished book is used in much the same way. While the language might be difficult for a child under the age of 9 or 10, I believe that children of all ages will be able to appreciate the story–its rhythm, its humor, and its message–especially when told directly to them by a parent, or grandparent, or some other important adult figure in their life.