Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (June 16)

It was about a decade after music professor Tammy L. Turner met blues promoter/producer Dick Waterman in a class at Ole Miss that she came to realize “he had an important story that needed to be told,” and she has captured his extraordinary career in the memoir, Dick Waterman: A Life in the Blues (University Press of Mississippi).

It was about a decade after music professor Tammy L. Turner met blues promoter/producer Dick Waterman in a class at Ole Miss that she came to realize “he had an important story that needed to be told,” and she has captured his extraordinary career in the memoir, Dick Waterman: A Life in the Blues (University Press of Mississippi).

Born in 1935 into an affluent Jewish family in Massachusetts, Waterman began his career in the 1950s as a journalist, honing his skills as a writer and photographer. It was his interest in the folk music of Greenwich Village and Cambridge in the 1960s that would lead him to a position as a music promoter in Boston, which eventually brought him to his “calling in life” with his pursuit of Mississippi Delta Blues artist Son House.

Waterman’s significant influence on decades of American music became evident in the careers of many big names in the music industry, in a variety of genres. Today he lives in Oxford, retired but “still busy.”

Turner resides in Kentucky, where she teaches a variety of university courses in music history. She is especially interested in 20th century music, including blues, jazz, rock, and classical music.

You hold a doctoral degree in music history from the University of Mississippi. Tell me about how you became interested in music–specifically blues music, and Dick Waterman in particular.

I had little exposure to blues music until I took Dr. Warren Steel’s African American musical traditions class at Ole Miss. It was in this class that I also met Dick. He was a guest at one of our class meetings and brought with him a number of his iconic black and white photographs from the 1960s, including a number of the early blues artists with whom he had worked.

Your research for this book is evident in the details, conversations, and interviews you reveal. How long have you known Waterman, and when did you realize his story should be published as a book?

Tammy Turner

Although I met Dick over two decades ago when he was a guest in our class, I did not have an opportunity to converse with him that day. I had classes of my own to teach and left immediately after the class ended. I graduated with my degree a couple of years later and moved away from Oxford.

As I continued my university teaching career, I eventually taught courses in both jazz and rock ‘n’ roll history. Blues music is a component in both courses, so I began to study blues more intently. I remembered Dick and his photos and, over the years, regretted missing such an excellent opportunity to talk with him about his work. In 2011, I traveled to Mississippi to do some blues research and was able to reconnect with him and we spent a delightful afternoon discussing his career.

Through a series of events, I helped arrange a photo exhibition and lecture for him in western Kentucky, where I reside. I enjoyed working with him and felt he had an important story that needed to be told. I approached him with the idea, and, after some consideration, he was amenable to the idea and granted me full access to the details of his life and his archives.

Waterman’s career in blues really began with his journey with Nick Perls and Phil Spiro into the Mississippi Delta in 1964 at the height of the Civil Rights movement to find bluesman Son House, who had faded into obscurity two decades prior. What did this lead to?

They found House, but not in Mississippi. Through contacts they made in Mississippi, they learned he was living in Rochester and drove there to meet him. In meeting House, Dick found a mission. It was in finding Son House that he found his calling and began his career in blues booking and management.

What would you say Waterman accomplished in the blues world (and other music genres)?

Dick played such a critical role in 20th century blues history. He was one of the three men who rediscovered Son House. Due to his tireless efforts, House came out of retirement for approximately 10 years and recorded an album with Columbia Records.

In June 1965, Dick founded Avalon Productions, which was the only agency at the time devoted solely to representing African American blues artists. He helped book some of the most important blues festivals of the 1960s and ‘70s, including the 1969 and 1970 Ann Arbor Blues Festivals, and he helped establish others.

He worked with several older bluesmen to reignite their careers, including Mississippi Fred McDowell, Skip James, Robert Pete Williams as well as others. He discovered a young singer/guitarist named Bonnie Raitt and assisted her career. He also convinced Buddy Guy to leave his day job as a mechanic in Chicago to pursue music as a full-time career. Musicians trusted him to handle their careers because he earned a reputation for honesty and integrity.

Waterman has left his mark on America’s musical history as a promoter and manager for artists who included many big blues names–and some of the biggest rock and other performers in the world, including James Taylor, Bruce Springsteen, and many others. What would you say drove him, and continues to drive him, to become such an important influencer in American music?

Dick inherited a tremendous work ethic from his father, who was a medical doctor. He also has a staunch sense of fairness and both a willingness and determination to advocate for others, especially those who are not in a position to advocate for themselves. It was never his goal to become famous, but to protect the older blues artists from exploitation, to demand competitive compensation for their work, and fight for royalties that some of them were being denied.

Today, Waterman lives in Oxford, where he moved in the mid-‘80s. What is he doing today?

Dick is retired, but still active. After a few decades away from photography, he returned to photographing musicians in the 1990s. In 2003 he published a book of his most iconic works titled Between Midnight and Day: The Last Unpublished Blues Archives and in 2006 wrote the text for The B.B. King Treasures book. He sells his photos, both new and old, at his website dickwaterman.com. He still receives requests for photo exhibitions/lectures and as a guest speaker discussing his work in the blues at various events and classes.

Tammy Tuner will be at Lemuria on Saturday, June 22, at 2:00 p.m. to sign copies of Dick Waterman: A Life in Blues.

But Thompson doesn’t just “cover sports.” His is more a literary style that frames the athletes he writes about in a light most have never seen cast on these figures: the struggles, the hopes, the disappointments, and oftentimes the personal failures of men and women who know firsthand the high cost required to make it to the top – and attempt to stay there. Included are the stories of Michael Jordan, Bear Bryant, Ted Williams, and others who know the pain and joy of success in sports at its highest levels. Thompson ends the book with a memoir of his late father and his personal longings to honor his dad’s memory.

But Thompson doesn’t just “cover sports.” His is more a literary style that frames the athletes he writes about in a light most have never seen cast on these figures: the struggles, the hopes, the disappointments, and oftentimes the personal failures of men and women who know firsthand the high cost required to make it to the top – and attempt to stay there. Included are the stories of Michael Jordan, Bear Bryant, Ted Williams, and others who know the pain and joy of success in sports at its highest levels. Thompson ends the book with a memoir of his late father and his personal longings to honor his dad’s memory.

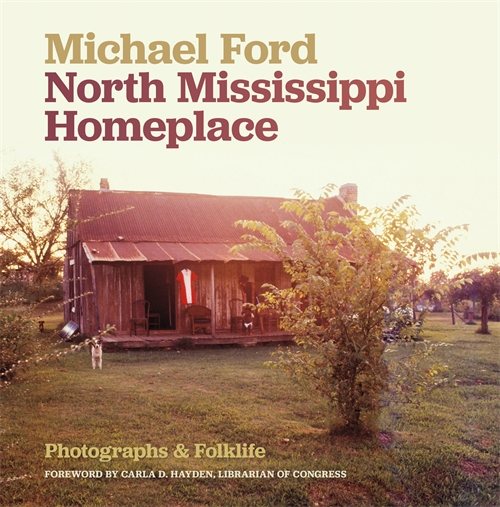

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

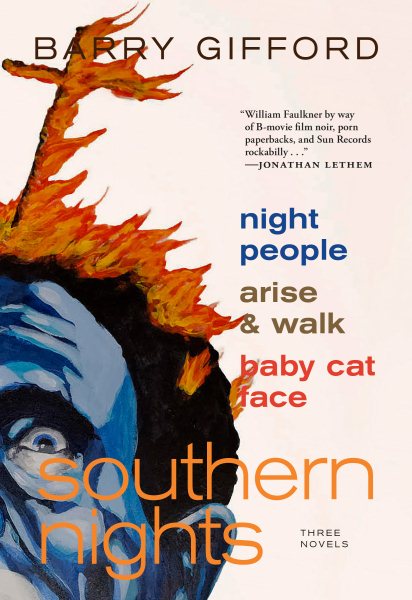

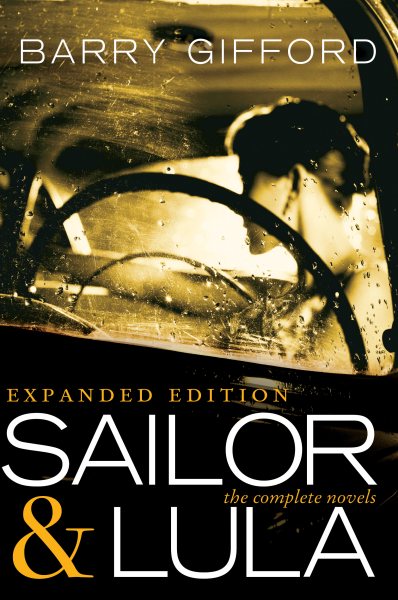

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing.

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing. “My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

“My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

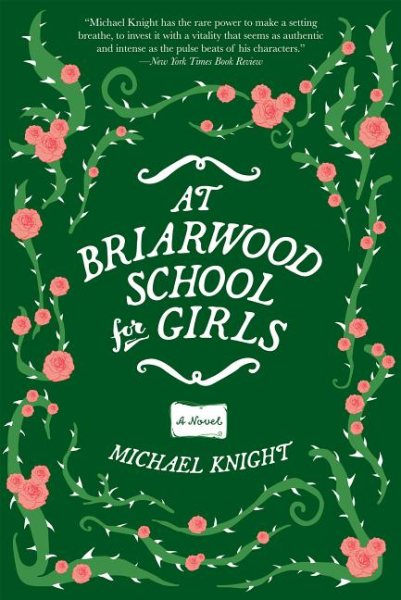

Knight’s new novel, set in 1994 at a boarding school in rural Virginia, is told from the perspective of Lenore Littlefield, a pregnant student of hidden talents and opaque motivations, and two lonely faculty members ostensibly charged with the education and guidance of Littlefield and her peers. The first person to whom Lenore reveals her predicament is her well-intentioned but somewhat indecisive history teacher, Lucas Bishop.

Knight’s new novel, set in 1994 at a boarding school in rural Virginia, is told from the perspective of Lenore Littlefield, a pregnant student of hidden talents and opaque motivations, and two lonely faculty members ostensibly charged with the education and guidance of Littlefield and her peers. The first person to whom Lenore reveals her predicament is her well-intentioned but somewhat indecisive history teacher, Lucas Bishop. Oxford’s Mary Miller highlights a Mississippi coastal town with a thoughtful tale of a middle-aged man facing an uncertain and lonely future–until he adopts a dog on a whim and one thing leads to another.

Oxford’s Mary Miller highlights a Mississippi coastal town with a thoughtful tale of a middle-aged man facing an uncertain and lonely future–until he adopts a dog on a whim and one thing leads to another.

Casey Cep in

Casey Cep in