Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (April 29)

With equal parts love and humor—not to mention brutal honesty—Southern storyteller extraordinaire Rick Bragg tackles a topic he admits he never thought he’d have the courage to swallow: food. And good Southern cooking.

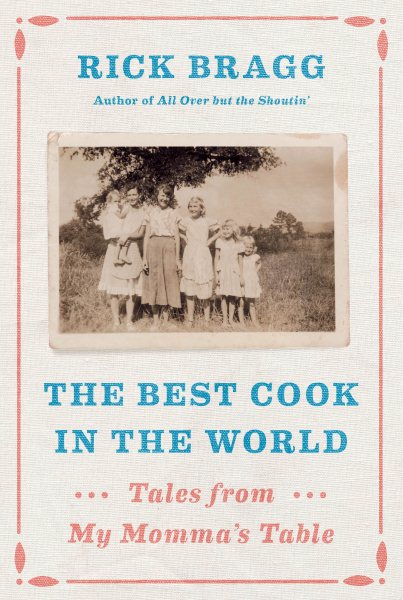

Fortunately for his readers, the release of his latest volume, The Best Cook in the World: Tales from My Momma’s Table, (Knopf) has proven that old-fashioned Southern fare is indeed in good hands.

“I’m not a cook,” the Possum Trot, Alabama, native is quick to say, but in this 490-page “food memoir,” he lets the stories of “his people” and their hilarious and sometimes heart-wrenching circumstances do the stewing and stirring.

But mostly, it’s a tribute to his mother, 81-year-old Margaret Bragg, whose skills in the kitchen, he says, are still unmatched. This is a woman who never—not once—used a cookbook, a written recipe, a measuring cup or even a set of measuring spoons to put a meal on the table. Her skills came from oral recipes and techniques that go back generations—some even to pre-Civil War days.

But mostly, it’s a tribute to his mother, 81-year-old Margaret Bragg, whose skills in the kitchen, he says, are still unmatched. This is a woman who never—not once—used a cookbook, a written recipe, a measuring cup or even a set of measuring spoons to put a meal on the table. Her skills came from oral recipes and techniques that go back generations—some even to pre-Civil War days.

Included are recipes for 74 Southern “soul food” dishes he says it took all of a year to convert into written form under his mother’s guidance.

A Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and a journalism professor at the University of Alabama, Bragg is a former New York Times reporter and the recipient of a Nieman Fellowship from Harvard University. A regular contributor to Garden and Gun, his previous books include All Over But the Shoutin’, Ava’s Man, Jerry Lee Lewis: His Own Story, and My Southern Journey: True Stories from the Heart of the South, among others.

Your new book is a “food memoir” and tribute to your mother, Margaret Bragg, who never used a recipe or owned a cookbook. Since you admit you are not a cook yourself, how did you get the idea to write this book, and why was it so important to you?

One of the reasons I did the book was because my mom had a heart attack, then developed cancer and had two years of chemo. When she first got sick about five years ago, her kitchen was just different when she was gone. When she’s home, the kitchen usually smells like bacon grease and that wonderful Red Diamond coffee. When she was gone it smelled more like lemon dishwashing detergent. Even the cold cast-iron skillets had a different smell.

I had tried before to cook her pinto beans and ham bone, and her beef short ribs, but it didn’t taste like hers. She never, never let us boys (Rick and his two brothers) in her kitchen when we were growing up. We’d have coal dust on us, or a live frog in a front pocket of our overalls. None of us learned any cooking from her.

I asked her where the recipe was written down for beef short ribs and she said, “I’ve never written down any recipe,” and I knew that. I’ve never seen her standing over a written recipe.

I love writing about food, something I do quite a bit, and every part of this book was always about the stories of people with my blood.

All of the recipes in this book come from stories—stories about fist fights or leaving a landlord in the middle of the night—because that’s how we live around here. And you would just remember the food that was there when it happened. The story about the time Sis, my mother’s father’s cousin, shot her husband in the teeth, and what that had to do with her chicken and dressing, is pure “writer’s platinum.”

I just thought I’d like to write these things down. I thought, “Why not? Do a book about food, and set recipes in it.”

Because your mom never uses measuring cups or spoons, you literally had to convince her to come up with the recipes included in the book. Was that a hard sell, since she says in the book, “A person can’t cook from a book”? And it must have been time-consuming creating recipes for so many dishes she knew by heart. How did you go about it?

There are two leather chairs in my momma’s living room. She sat in the one on the left and I sat in the one on the right. I leaned close to her to talk about how much of what would go into the recipes, and it took For. Ever.

To her, there is no “half cup of flour.” She would say “just get a good handful” or “a real good handful.” A tablespoon to her means the big spoon in the kitchen drawer. Or she would say use a “smidgeon” or—my favorite—“some.” It really didn’t matter the quantity of ingredients in the recipes. It’s the process. You have to leave a lot of it to common sense.

It took, probably, a solid year.

I’ve been asked if we tested the recipes in the book. My ambition was to share some of the stories of the food, and some recipes, as best I can. That, and not poison anybody.

This book is not about your typical “cookbook” type of food—there are no restraints on the use of fat (often in the form of lard), or sugar, eggs, meats or other rich ingredients that have lost some favor over the past few decades. What kind of readers and cooks do you hope will be drawn to this book?

First of all, it’s not a cookbook. If people are buying it just as a cookbook, that’s not the point. What I hope happens is that people will enjoy the true narrative, the history.

I’m not a cook and I’m not a cookbook writer. This was a chance to write about where the food came from. I hope that what people in the Upper East Side (of Manhattan), London, Connecticut and everywhere else will enjoy is the narratives, and see the value of the food.

Your mom insists she is a “cook”—not a chef. Please explain what that boils down to.

A chef expects to be called “chef,” and his underlings have to refer to him as such. A cook doesn’t care what you call him or her. It’s not about pride, but pretentiousness.

There is a great deal of family history in The Best Cook in the World—not only unique, but humorous! Tell me about the process of putting these stories together.

We didn’t have to cobble the stories together. A lot of times the food would spark the story, like the chicken and dressing story. There were recipes I wanted to put in there, but I just didn’t have a good story—like peanut butter pie, fresh garden vegetables and Aunt Juanita’s peanut butter cookies. Now, commodity cheese, I have a great story. Or Ava’s tornado story—I’ve wanted to include that story somewhere for 15 years, and this was my chance.

Among the recipes that are included, what are some of your favorites—and have you, or will you—cook them yourself?

Rick Bragg

I can cook a mean biscuit, but I usually won’t if I can get some good store-bought ones. I make red eye gravy with ham and grits—the good kind. A chocolate pie sounds like something I could do.

I don’t have the patience my momma has, and I can’t make any of it taste like she does.

One of my favorite things she made us was fried pies—but she recently told my brother Sam and me that she never made that. She had forgotten. That was the reason to do this book.

Rick Bragg will beat Lemuria on Friday, May 4, at 5:00 to sign and read from The Best Cook in the World: Tales from My Momma’s Table. The Best Cook in the World is a 2018 selection for Lemuria’s First Edition Club for Nonfiction.

Comments are closed.