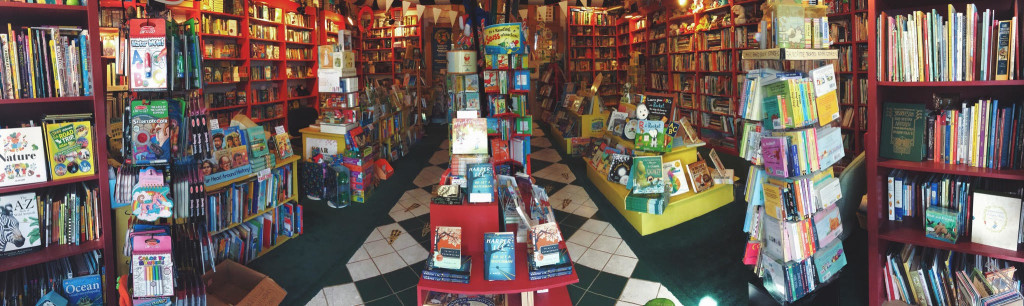

I don’t need to spend much time telling you this book is going to make waves, you probably already know that. I’ve walked into a restaurant holding the book and was haphazardly ushered into a table of strangers demanding to know how I got my hands on a copy of Between the World and Me before its release date. In another instance, a customer at Lemuria asked me what was my favorite bourbon, and offered to go to the liquor store that moment to find an adequate bribe to loosen my clutch on the book. Sorry man, Between the World and Me is worth more than the most expensive bottle of bourbon.

Put down what you’re reading and pick up Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. It won’t take up more than a day of precious reading time. I am positive you will easily find profundity in Coates’s words regardless if you’re a man, woman, white, black, skinny, fat, carnivore, vegan, liberal or conservative.

Put down what you’re reading and pick up Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. It won’t take up more than a day of precious reading time. I am positive you will easily find profundity in Coates’s words regardless if you’re a man, woman, white, black, skinny, fat, carnivore, vegan, liberal or conservative.

Coates’s eloquent prose has given me chills as I sat reading in the blistering Mississippi summer, and his fiery gestures have made me sweat when I lay on my back reading with my AC set on 68. Rather than spoil his message by trying to use my words to explain Coates’s words, I want to share how this book has forced me to remember something tragic in my own history and made me examine it using new lenses.

Between the World and Me covers a lot of ground in a mere 152 pages. But one section left me in a trance it forced me to remember a story from my own history, which I have attempted to erase from my memory by burying it in silence.

Coates speaks to his time at Howard University as a momentary utopia, or in his words “The Mecca.” In his Mecca, for the first time, Coates is comforted by being around people like him—black men and women with vast intellectual concerns. But, the love he felt at Howard’s “Mecca” is shattered when a colleague is murdered in a case of senseless police brutality.

His words forced me to think. Between the World and Me took me back to the time I spent in my personal Mecca and it’s own violent end. It forced uncomfortable thoughts of my own whiteness to the surface, leaving my pores bubbling with anxious self-reflection.

* * *

I remember paying for my lunch at my public high school line and standing there, motionless, trying to gulp down an anxious stone in my throat. Where do I sit today? There dozens of tables, each comprising a community of kids, each inward looking, each excluding the next table as if they weren’t sitting together in the same room. Uniformed, sunburnt white baseball players sat together flirting with the future home-coming queens. The black footballers sat together showing each other their new, first-wave smart phones. The lower-income white kids sat together in their baggy-pants, throwing tater-tots at each other when the eyes of the disciplinarians turned away.

There was one table that was a bit less populated than the rest. A black kid wearing a Jay-Z t-shirt was beating his palms and a #2 pencil in alternating rhythms on the table. They were taking turns practicing their best Wayne impressions, spitting freestyles fraught with vulgarities about women, weed, and violence. They noticed when I sat down, but they didn’t make a big deal about it, they actually slid down to close the awkward gap I had left open because of my anxious uncertainty. I ate my processed chicken nuggets and bobbed my head in time with the tapping of the #2 pencil.

I ate my lunches this way for the next few years. We didn’t usually talk about blackness and whiteness, but it was coldly observed in the absence of their fathers, the warmth of their mothers toward me, and the distance of their older cousins that flashed gang signs and slapped complex handshakes.

Our sessions left the lunch room and went into the bedrooms of our suburban middle class homes. When it came my turn in the cypher, I’d let loose all the anxiety I’d scribbled in my journals into lyrics manifested by a two step beat and a bass drop. When my eighth bar had landed, the guys would burst with laughter and say, “Damn white boy got some words.”

This was the first time my passion for words made me feel cool. I have always manically been putting words into journals, secretly hoping to share them—not only to share them but for my words to make me cool. These young lyricists were The Mecca for me, not only did they listen to my words, but they introduced me to friends and friends of friends who also thought rhyming and beats were cool. I was at home in the comfort of not having to guard or hide the sincerity of my passion.

There were four kids I hung out with routinely, and we became pretty damn close. They were black guys and I am a white guy, and there wasn’t any ignorance of that fact. Between the World and Me reminded me how perversely race issues can slither into Mecca and usurp the comfort Mecca provides.

We were about to graduate. We had done alright in school. Good enough to go to college if we were willing put our noses to the grind stone. I ended up getting accepted to Millsaps College, one of us went into the airforce, and the other two ended up getting felony charges.

One of those kids pled guilty and took two years jail time, and the other accepted to be a CI and try to get a bad guy arrested.

I was running late for a morning class during my sophomore year of college and I got a call from the friend who took the jailtime in Parchman. He sounded completely different. Alive with rage. Frankly, he sounded ready to kill. Then he told me that our friend, the one that took the offer to be a CI, was found dead in an abandoned home with his hands duct taped behind his back and a bullet wound to his forehead. The friend on the phone swore revenge and he thought he knew on whom it should befall.

I walked to class along the giant wrought-iron fence topped with razor wire that “secured” our luxury automobiles and macbooks from the larger black community surrounding my college.

The class was Civil Liberties. It was a nice spring day and we sat outside and discussed Brown v. Board of Education. The professor was mid sentence when a staccato burst of gunshots a block or two away cut him off. One of the white kids laughed, detached from the reality outside the safety of the precious spools of razor wire. He said, “That’s Jackson for you.”

I stood up, and in a rage of expletives I excused myself. I dropped the class and never went back.

I was angry with myself for being comfortable. Angry that my friends, who had first showed me that it was ok to be the person I saw myself as, were killing, imprisoned or dead. Angry that it was too hard to talk with new friends about what happened to them. I was angry that I was in college when I didn’t deserve it any more than one of them. I was angry at my own whiteness, and frustrated at the fact that whiteness had mastered me with a private education where it was ok to analyze Brown v. Board of Education and laugh at black on black violence in the same breath.

I’ve been to Mecca before, and my Mecca ended much the same way as Coates’s—this is not a coincidence, this is evident that the emotions and observations expressed in Between the World in Me are truthful. Racially driven violence is systematic and intrinsic in today’s America; there is no way to escape application to you, whoever you are and wherever you are reading this.

Ta-Nehesi Coates in Between the World and Me has empowered me to be able to share this story with you; a story I’ve tried to forget for so many years and hardly ever shared. I’m a white guy and can never understand the suffering black bodies are put through. But, Coates has forced me to re-examine what it means to black and what it means to be white. Blackness and Whiteness are real things—tangible things. Coates explains why whiteness and blackness cannot be circumvented by neo-liberal policies of colorblindness. Race issues are just as American as hot dogs, and we must constantly examine and re-examine the mechanics that propel racial violence and mistrust because they are parallel with the grand mechanics of domination and oppression. Pick up the book. Read it and think about who you are and honestly ask yourself how race has affected your life.

Please direct any thoughts, comments or questions to Salvo Blair at salvo.blair91@gmail.com

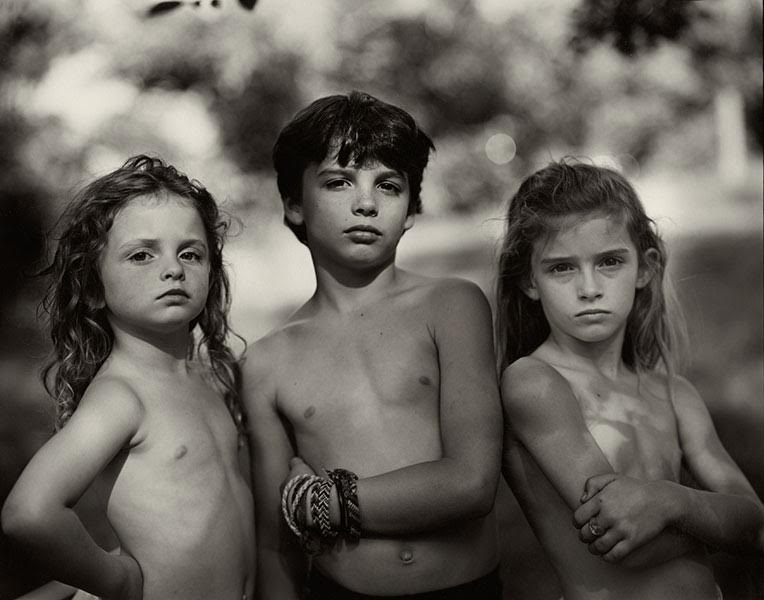

Mann’s new book, Hold Still is not just a photography book, she has let us step into her life by making this book her memoir. I’ve always enjoyed photography, and I’m not going to lie, at first I only picked this book up in the store to flip through the photos. I was told that she had been to a “body farm” and taken photos of the human body’s stages of decomposition and damn, she really did (yes, I’m the gross kid that thinks that stuff is cool, sorry about it). This book is filled with photos from the birth of one of her children to photos of family relics. All of which are intriguing and beautifully done.

Mann’s new book, Hold Still is not just a photography book, she has let us step into her life by making this book her memoir. I’ve always enjoyed photography, and I’m not going to lie, at first I only picked this book up in the store to flip through the photos. I was told that she had been to a “body farm” and taken photos of the human body’s stages of decomposition and damn, she really did (yes, I’m the gross kid that thinks that stuff is cool, sorry about it). This book is filled with photos from the birth of one of her children to photos of family relics. All of which are intriguing and beautifully done.