Tom Piazza will be at the Eudora Welty House TONIGHT at 5:00 to sign and read from “A Free State”.

By Jim Ewing. Special to The Clarion-Ledger

Tom Piazza’s “Free State” offers a fascinating study on the nature of freedom in the guise of a thought-provoking novel.

Tom Piazza’s “Free State” offers a fascinating study on the nature of freedom in the guise of a thought-provoking novel.

Set in the years before the Civil War, “Free State” focuses on the chance coming together of a black man, who calls himself Henry Sims, and a white man, who calls himself James Douglass. Both are assumed names by characters seeking freedom and a new identity from the lives they were born into and their grim pasts.

Douglass is of Irish descent, the youngest son of a Pennsylvania farmer who chafed under the grueling chores of farm life and the physical abuse of his father and older brothers. He seeks freedom by joining a traveling circus and becomes enthralled by the burgeoning fad of minstrelsy — traveling troupes of musicians who adopt a grotesque rendition of Old South plantation life by performing in black face, or covering their faces with burnt cork. He rises in his musical ability and forms his own minstrel group in Philadelphia, Penn., a free state, which in America, it turns out, is not so free.

But it’s all theater, a masquerade, set for public consumption amidst an imagined tapestry of faux aristocratic plantation owners bemused by the “jollity” of enslaved blacks happily entertaining for their masters. Only the beauty of the music is real.

Why minstrelsy? “The practice of ‘blacking up’ had spread … to feed a hunger that had gone unrecognized until then,” Douglass reminisces. “ In it, we — everyone, it seemed— encountered a freedom that could be found there and there only. As if day-to-day life were a dull slog under gray skies, and the minstrels launched one into the empyrean blue.”

“When I first heard the minstrels,” he recalls, “…I felt as if I had been freed from a life of oppressive servitude.”

Thus, a white man finds freedom by impersonating a black slave.

Douglass’ façade meets horrific reality when he meets Sims, a runaway slave from Virginia, seeking to escape his master father and a slave hunter, Tull Burton, he has hired to track him down. Burton is evil incarnate, a fascinating study of the devil in human flesh, who delights in the torture of those he seeks. Like the society that imposes slavery and inequality even under the guise of democracy and commitment to human freedom, he is unrelenting and devoted to his cause of using the law to brutally enforce the codes of human bondage.

The story itself is absorbing as Douglass and Sims forge a tenuous bond and adopt a rational solution to both of their problems. Sims and Douglass attempt to pursue their love of music while supporting themselves in a world that twists notions of life and livelihood along the lines of race.

Their solution — for Sims, a black man, to assume black face in order to evade laws barring black people from public performance — exposes the theater of the absurd that was the antebellum South. In it, a white man could find freedom only by pretending to black; a black man could only find freedom by masking that he was black by pretending to be black.

The truth of this preposterous state of “freedom” finds echoes today as American society still struggles with issues of race and equality. The true face behind the mask is that the world limits freedom and equality no matter how devoted and pure one’s intention and desires may be, and that we all play out our roles in often absurd conditions to pursue a free state.

It’s an absorbing tale and a parable that exposes the incongruities of living in a democracy still colored by inequality.

Jim Ewing, a former writer and editor at The Clarion-Ledger, is the author of seven books including Redefining Manhood: A Guide for Men and Those Who Love Them, now in bookstores.

This fragment of “Ray” also differs from the complete version of “Ray” published by Knopf in 1980 as pages 12-26. The publication of Gorgas Oak’s “Neighborhood” provides a rare opportunity to compare an early draft of a literary text with its final form.

This fragment of “Ray” also differs from the complete version of “Ray” published by Knopf in 1980 as pages 12-26. The publication of Gorgas Oak’s “Neighborhood” provides a rare opportunity to compare an early draft of a literary text with its final form.

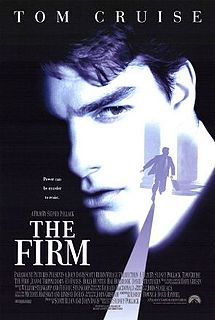

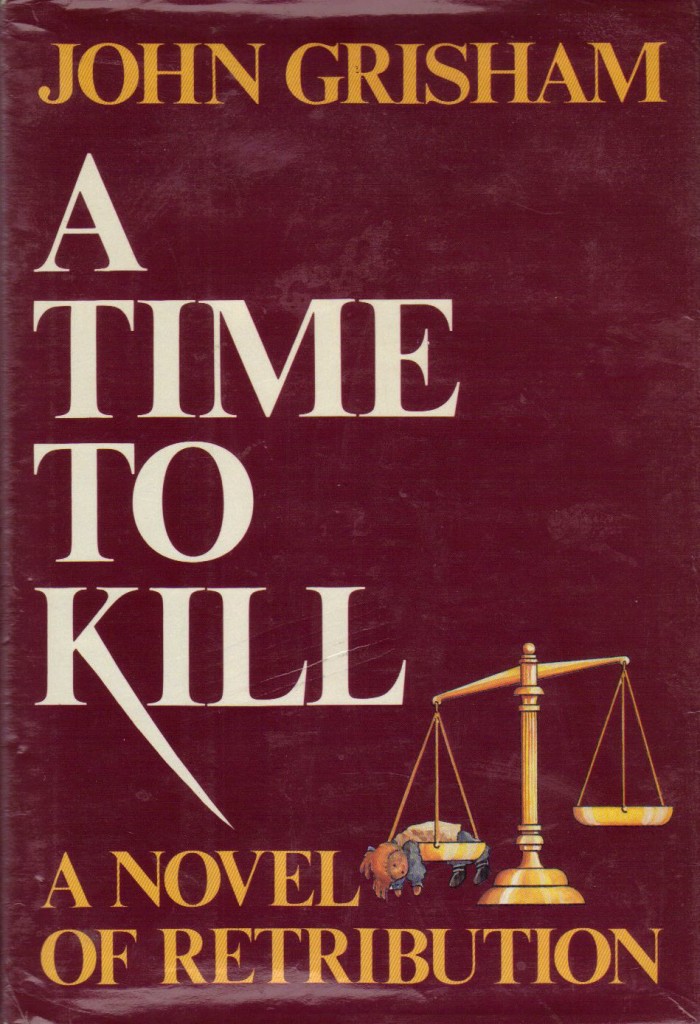

By 1993, John Grisham’s name had become synonymous with the legal thriller and he had published four of his most popular books: “A Time to Kill” (1989); “The Firm” (1991); “The Pelican Brief” (1992); and “The Client” (1993). This same year Doubleday bought the rights from Wynwood press to reissue “A Time to Kill” in hardback. Meanwhile, “The Firm” and “The Pelican Brief” were box office hits in the movie theater, expanding Grisham’s fan base even further.

By 1993, John Grisham’s name had become synonymous with the legal thriller and he had published four of his most popular books: “A Time to Kill” (1989); “The Firm” (1991); “The Pelican Brief” (1992); and “The Client” (1993). This same year Doubleday bought the rights from Wynwood press to reissue “A Time to Kill” in hardback. Meanwhile, “The Firm” and “The Pelican Brief” were box office hits in the movie theater, expanding Grisham’s fan base even further.

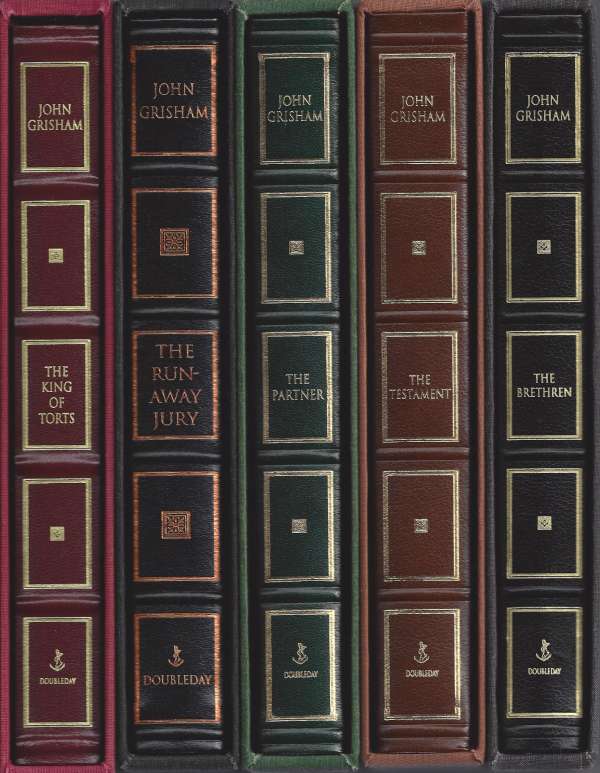

Every year since “The Client,” Doubleday has issued a limited edition of each of John Grisham’s novels. The legal thrillers are leather-bound, signed and numbered, have decorated end papers, gold stamping, a ribbon marker and are housed in a slipcase. The nonlegal thrillers like “Ford County,” “Skipping Christmas” and “A Painted House” are issued cloth bound and as a group are not always uniform in size as the legal thrillers are. An entire limited edition collection in fine condition—from “A Time to Kill” to the latest book—is valued at around $15,000.

Every year since “The Client,” Doubleday has issued a limited edition of each of John Grisham’s novels. The legal thrillers are leather-bound, signed and numbered, have decorated end papers, gold stamping, a ribbon marker and are housed in a slipcase. The nonlegal thrillers like “Ford County,” “Skipping Christmas” and “A Painted House” are issued cloth bound and as a group are not always uniform in size as the legal thrillers are. An entire limited edition collection in fine condition—from “A Time to Kill” to the latest book—is valued at around $15,000.