By Jim Ewing. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (April 29)

What makes a writer a writer? Or a Southern writer, especially?

Is it that one writes and, hence, is a writer? Or lives in the South or writes about the South?

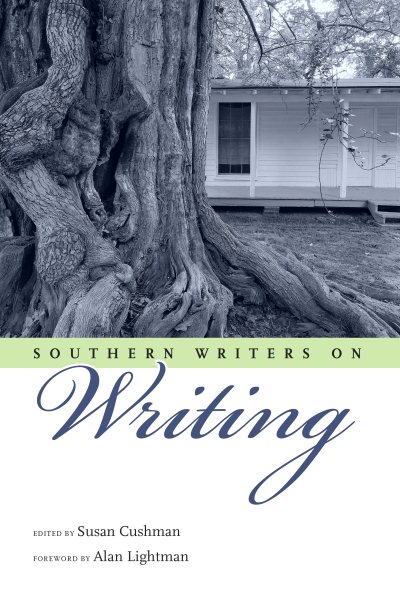

In Southern Writers on Writing, edited by Susan Cushman, the answers to these questions might not be as easy as they seem.

In Southern Writers on Writing, edited by Susan Cushman, the answers to these questions might not be as easy as they seem.

Fourteen women and 13 men struggle to answer the question of their calling and their responses show a nuanced look at why, and how, these authors came to be called Southern writers.

They include such well-known authors as Michael Farris Smith, Jim Dees, W. Ralph Eubanks, Harrison Scott Key, Cassandra King, and Julie Cantrell. They quote as mentors such luminaries as Rick Bragg, Willie Morris, Barry Hannah, Shelby Foote, Ellen Douglas, and Walker Percy.

But, still, the answers prove elusive. Dees says it requires “insane courage” to “take the plunge” and commit one’s innermost thoughts to an uncaring, or uncertain, universe.

Joe Formichella says: “The truth is that you write because you can’t not write.”

Patti Callahan Henry, among other reasons, says: “I write because the stories inside have to go somewhere, so why not on paper?”

Some of these writers are from the South, others just came to be here. Like Sonja Livingstone, who found Southern writers “crept up” on her, seeming familiar, drawing her to the region and lifestyle. Most of all, the way Southern writers write is alluring, unleashing inner secrets, she explains, “set out like colorful laundry flapping on a line, (that) I’d learned to keep folded and tucked away.”

Cantrell, who hails from Louisiana, confides that Southern writing taps all the senses. “When we set a story here, we not only deliver a cast of colorful characters, we share their sinful secrets while serving a mouth-watering meal…. The South offers a fantasy, a place where time slows and anxieties melt away like the ice in a glass of sugar cane rum.”

“The South is nothing less than a sanctuary for a story,” she adds. “It is the porch swing, the rocking chair, the barstool, the back pew.”

Being a Southern writer, writes Katherine Clark, is an opportunity and a burden, especially when you consider that you’re entering literary territory with nationally and internationally known explorers, such as William Faulkner, Flannery O’Conner, Eudora Welty, Tennessee Williams, James Agee, Harper Lee, and so many others.

But, as John M. Floyd points out, “Within several miles of my hometown lived men and women who were known only as Jabbo, Biddie, Pep, WeeWee, Buster, Puddin’, Doo-spat, Ham, Big ’un, Nannie, Bobo, Snooky, and Button. How could folks with those kind of names be anything but interesting?”

“Writing” is fascinating reading, and, of course, enthrallingly written, as can be expected by writers writing about writing. But it’s also an encouragement for those who have thought about writing, but haven’t done it, thinking there’s some kind of secret to it.

If there is an “inside secret” to Southerners wanting to write, maybe that’s plain, as well.

The South, writes Jennifer Horne, writes itself every day, offering up “a hunter’s stew of history and hope and horror.”

It’s all around us.

As Floyd points out: “In my travels I’ve been inside bookstores all across the nation, and I have yet to see a section labeled ‘Northern Fiction.’ Maybe that, in itself, is revealing.”

Jim Ewing, a former writer and editor at the Clarion Ledger, is the author of seven books including his latest, Redefining Manhood: A Guide for Men and Those Who Love Them.

Susan Cushman, John Floyd, and Jim Dees will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, May 2, at 5:00 to sign and read from Southern Writers on Writing.

I know that Charles Frazier is most known for his novel,

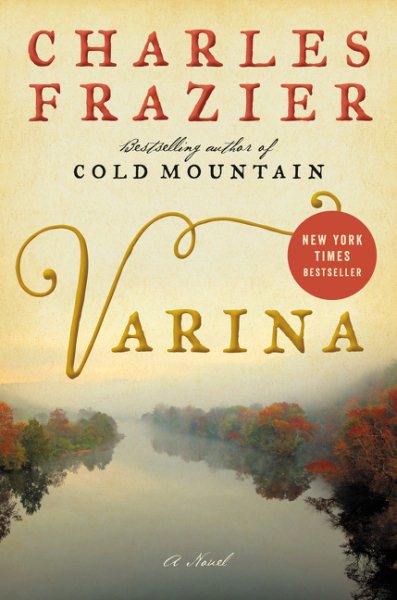

I know that Charles Frazier is most known for his novel,  Married at 17 to a man nearly 20 years her senior, Varina is thrust into political life during the brutality of the Civil War. She suffers the loss of several children and then decides to rescue a black child named Jimmie to raise as her own.

Married at 17 to a man nearly 20 years her senior, Varina is thrust into political life during the brutality of the Civil War. She suffers the loss of several children and then decides to rescue a black child named Jimmie to raise as her own.

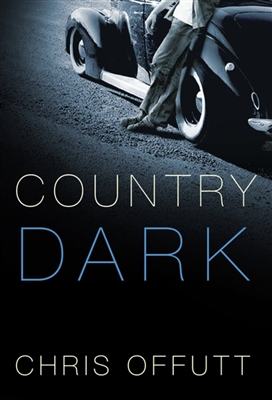

After nearly two decades, award-winning author and screenwriter Chris Offutt of Oxford has released his long-awaited next novel–and this time it is definitive Southern Gothic, as he lays out the story of

After nearly two decades, award-winning author and screenwriter Chris Offutt of Oxford has released his long-awaited next novel–and this time it is definitive Southern Gothic, as he lays out the story of

You win the prize for my favorite question about The Fighter so far. Maybe it’s because we are all fighters. We all have made mistakes, we have hurt people who love us, we have done things we regret and knew we were going to regret it as we were doing it, and we all fight to try and fix what we’ve done after we’ve broken it.

You win the prize for my favorite question about The Fighter so far. Maybe it’s because we are all fighters. We all have made mistakes, we have hurt people who love us, we have done things we regret and knew we were going to regret it as we were doing it, and we all fight to try and fix what we’ve done after we’ve broken it. Those are the questions readers will be asking themselves after the final page is turned in

Those are the questions readers will be asking themselves after the final page is turned in

It began with a simple what-if question: What if a miraculous-seeming event happened today, in America? An event that defied all explanation? What would it look like–in the press, on social media? What kinds of cultural fault lines would it cause to rumble? And what effects–aside from the physical recovery–would this event have on the lives of those it touched? It was a spiral of questions.

It began with a simple what-if question: What if a miraculous-seeming event happened today, in America? An event that defied all explanation? What would it look like–in the press, on social media? What kinds of cultural fault lines would it cause to rumble? And what effects–aside from the physical recovery–would this event have on the lives of those it touched? It was a spiral of questions.