Written by Johnathan Odell, author of The Healing and a new rendering of his debut novel, The View from Delphi: Miss Hazel and the Rosa Parks League. Available on February 4, Rosa Parks’s 102nd birthday.

When I was interviewing Mississippians for my book, an elderly black man talked about his days as a sharecropper. He summed up his experience like this, “When God handed out possessions, he must have give the black man the plow and the white man the pencil.” It was his way of saying that under Jim Crow, the black man did all the work, but no matter how big a crop you brought in, it was the figures the white man put down in his ledger that decided if there would be any money that season, or if the sharecropper would remain in economic servitude to the land owner.

I have also found that saying helpful in understanding the way the historical record is maintained as well. It’s now widely accepted that if a white man is writing the story, the role of blacks tend to get diminished as agents of their own liberation. They are often portrayed as longsuffering victims waiting to be saved by the benevolent acts of white people. Black heroes have a hard time finding themselves in print. My black friends call this “Killing the Mockingbird Syndrome”, for the way that famous book relegates blacks to pitiful, powerless dependents. As I say, though, we are becoming aware of this dynamic, thanks to a growing number of black historians.

But as I researched the Civil Rights period for “Miss Hazel in the Rosa Parks League,” I ran into another significant discrepancy in how the story is told.

To change up the saying a bit, if the white man got the pencil, and the black man got the plow, then the black woman got the harness to pull that plow through the stony fields of the Civil Rights Movement. Her acts of courageous resistance are even more overlooked by history than that of the black man.

I think there are multiple reasons for this. One is the nature of the violence during that time. Black men were constantly in the crosshairs. Face it, most of racism in the South stems from white fear that black men want white women (and the deep insecurity that it could be reciprocal!). So the focus of white paranoia was on black men. They were the ones whites had to keep an eye on, so the risk was higher for them to overtly resist. Black women were the lowest of the low as for perceived power and threat to white superiority. They could get a lot of things done their men could not because they were more “invisible.” They had jobs that took them into the most intimate spaces of the white life. They could come and go more freely. They could pool information, influence through personal relationship with white women. They were uniquely positioned to subvert white power, but it was from the shadows.

And of course patriarchy exists in the black community just as it does in the white community. The public spokespeople for African Americans have historically been male just as they had been for whites. In the 1950’s and 60’s, if white male leaders were going to deal directly with anyone it would have to be black leaders who were also male. “Man to Man.” That was the culture. Newspapers, T.V, radio, all the communication channels that African Americans needed to get their message out were necessarily looking for the black male spokesperson for the real story. The country as a whole wasn’t ready to see women of any race as leaders of a legitimate movement. The credible face on the evening news needed to be a Martin Luther King, not a Rosa Parks.

So it may have been a necessary convention, but the tragedy is that still we give those public male faces most of the credit, when it was an army of women who assumed the lion’s share of the risk and got the job done. That’s not a new story, and unfortunately, not a defunct one.

The truth is, when it came time to publically defy white authority throughout the South, it was black women who took to the streets, to the registrar’s office and to the whites-only schoolhouse. Mississippian Fannie Lou Hamer, one of the most influential figures in the Civil Rights story, male or female, put it bluntly. She said it wasn’t the male “chicken eatin’ preachers” who were the backbone of the movement, but the fieldworkers like herself, the illiterates, the mothers with nothing else to loose, the sassy “Saturday night brawlers.”

Even today, this bias for male heroes still serves to obscure the real contributions of women like Rosa Parks, who is often portrayed as a tired, longsuffering, meek woman whose feet were tired. When in actuality she was a seasoned activist, youthful and full of passion. She had been stepping out into the battlefield long before she got on that bus, and kept stepping long after.

Praise for MISS HAZEL AND THE ROSA PARKS LEAGUE

“A terrific writer who can take his place in the distinguished pantheon of Southern fiction”

–Pat Conroy, author of The Prince of Tides, The Great Santini

“Here it comes—barreling down the track like a runaway train, a no-holds-barred Southern novel as tragic and complicated as the Jim Crow era it depicts…. This is a big brilliant novel whose time has come.”

–Lee Smith, author of The Last Girls and Guests on Earth

“With its deftly drawn characters, delicious dialogue, and deeply satisfying and hopeful ending, this fine novel deserves to win the hearts of readers everywhere. Book clubs, this one is definitely for you!”

— Meg Waite Clayton, author of The Wednesday Sisters

“Odell vividly brings to life a fabulous cast of characters as well as a troubling time in our not-so-distant past. You won’t want to miss this one!”

— Cassandra King, author of The Sunday Wife and Moonrise

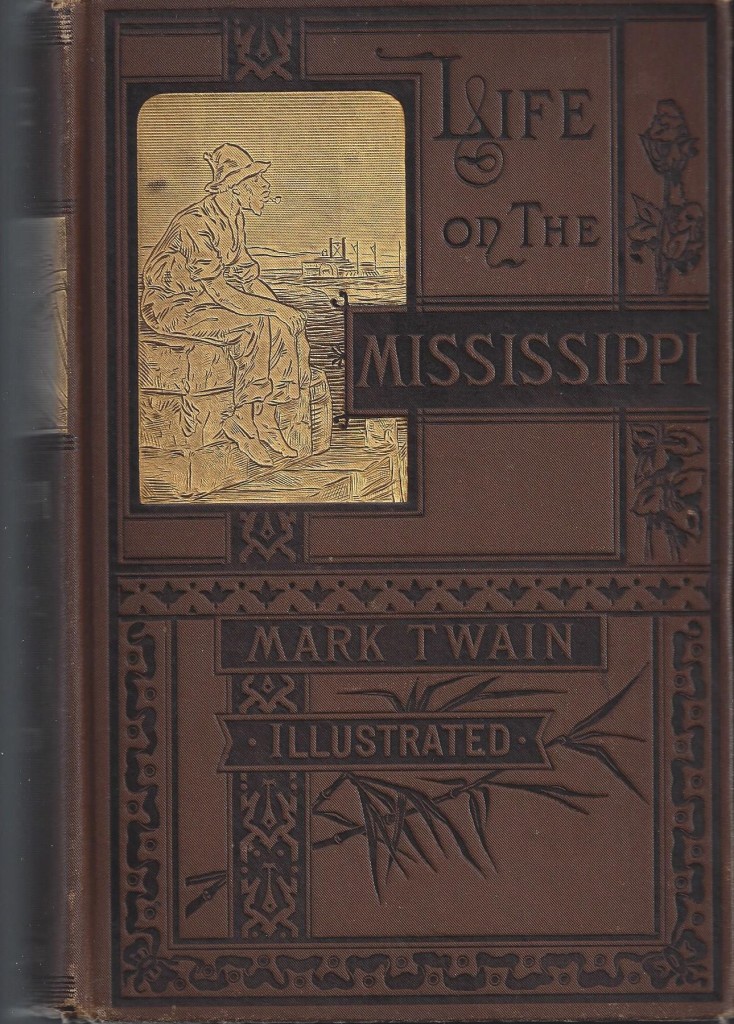

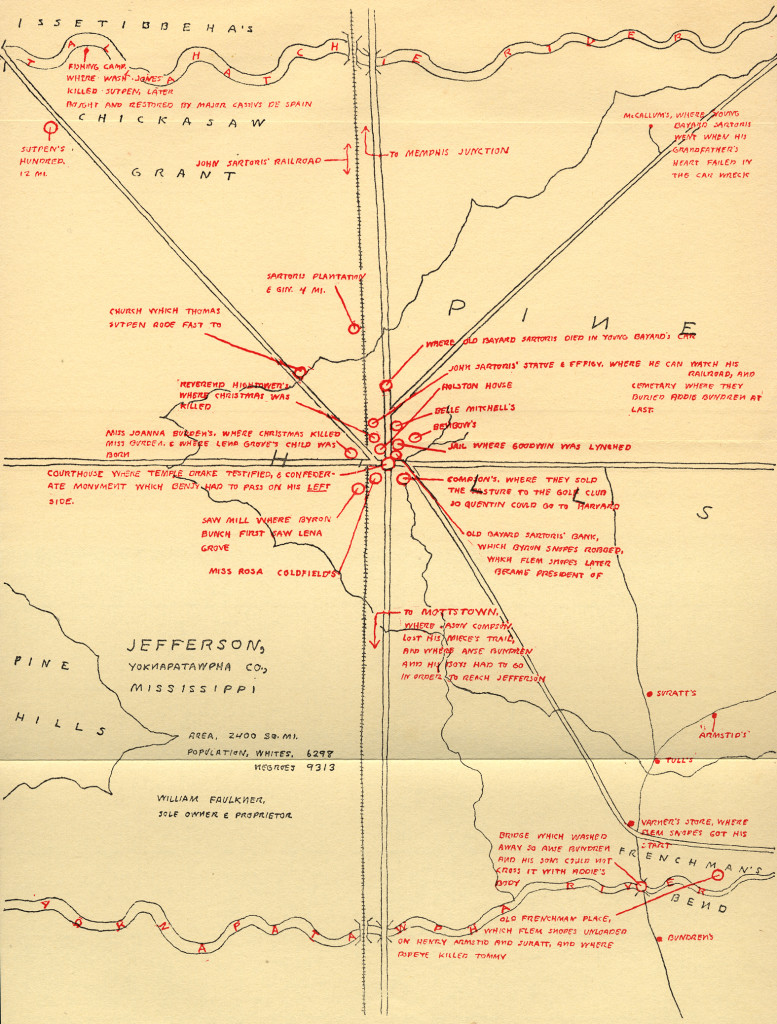

Certainly, no one was more aware of the complexity of “Absalom” than Faulkner himself. After much editorial work, Faulkner created three reader’s guides to appear at the end of the book: a genealogy, a chronology, and a map of Yoknapatawpha County. The map was special because the publisher had to pay extra to have it tipped in to the first 6,000 copies; the map was also printed in two colors. Random House was eager to make the book as beautiful as possible because “Absalom” was Random House’s first Faulkner book to publish. Earlier that year, Bennett Cerf of Random House had bought Smith & Haas, a small publisher that had been struggling to make a profit even though it had a line of great authors. Cerf wrote in his

Certainly, no one was more aware of the complexity of “Absalom” than Faulkner himself. After much editorial work, Faulkner created three reader’s guides to appear at the end of the book: a genealogy, a chronology, and a map of Yoknapatawpha County. The map was special because the publisher had to pay extra to have it tipped in to the first 6,000 copies; the map was also printed in two colors. Random House was eager to make the book as beautiful as possible because “Absalom” was Random House’s first Faulkner book to publish. Earlier that year, Bennett Cerf of Random House had bought Smith & Haas, a small publisher that had been struggling to make a profit even though it had a line of great authors. Cerf wrote in his

“Breathing Lessons” by Anne Tyler. Franklin Library: Philadelphia, PA: 1988.

“Breathing Lessons” by Anne Tyler. Franklin Library: Philadelphia, PA: 1988.