Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (August 13).

Author and journalist Mark Bowden challenges a new generation of readers to question America’s involvement in Vietnam as he examines, with laser precision, the bloody battle for the city of Hue (pronounced “whey”) in his newest release Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam (Grove Atlantic).

Author and journalist Mark Bowden challenges a new generation of readers to question America’s involvement in Vietnam as he examines, with laser precision, the bloody battle for the city of Hue (pronounced “whey”) in his newest release Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam (Grove Atlantic).

Nearly 50 years later, the man who is perhaps best known for his blockbuster Black Hawk Downexposes in detail the sense of betrayal Americans felt when the war they had been told the country was handily winning suddenly became the war they could, at best, withdraw from “with honor.”

The author of 13 books, Bowden now writes for The Atlanticand Vanity Fair, among other magazines. He was a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer for 25 years. A native of St. Louis, he now lives in Pennsylvania.

Bowden will participate in the History Makers panel during the Mississippi Book Festival August 19 in Jackson. The event will be at noon in the Old Supreme Court Room of the Mississippi State Capitol Building.

What spurred your interest in writing this detailed historical account of the 1968 Tet Offensive during the Vietnam conflict?

Vietnam has been for me a subject of tremendous interest throughout my life. I was 16 years old when Tet, this battle, happened. Myd ad and I battled about Vietnam then, with me against (the war), him for it, with neither of us having a whole lot of knowledge about it.

So, at a fairly young age, I started reading the newspaper; and, on my own, I subscribed to Time magazine. I would go the library and grab books (about it) at random off the shelf. I started reading sytematically in order to bone up for arguments with my dad about Vietnam. These habits I developed of researching and writing led me to becoming a journalist and writer.

I had never written about Vietnam before. In the epilogue, I talk about how this battle for Hue in the Tet Offensive was a turning point for the American battle in Vietnam–and (Gen. William Westmoreland’s) refusal to fact facts about this, the single most important event in the war.

The more I thought about it, this battle was the sort of dramatic episode that, if I could dig deep into this moment, it could become a lens into the war itself. Hue had all the features of the war–heroism and fears of both the American and Vietnamese soldiers, and politics in Washington that shaped military strategies. It gives a pretty good glimpse of the bigger war.

Explain the historical significance of this event.

The U.S. began investing really heavily in Vietnam in 1964-65. There had been advisers before that who had been helping the Vietnamese government, but it was then that LBJ (President Lyndon Baines Johnson) made the decision to send large numbers of troops.

In 1967, there were half a million American soldiers in Vietnam. The president and Westmoreland were assuring the American people this would be an easy war in this rag-tag little country. Westie had come back to Washington and he gave a speech to the National Press Corps (in November 1967) saying that the war was well in hand and that they were entering the “third phase,” where troops would start returning home.

In January 1968, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong launched surprise attacks and took Hue, the third largest city in South Vietnam–hardly an offensive by a depleted foe. Hue was a tremendously significant place, as Vietnam’s ancient capital and center of culture and religion.

Clearly, Hue had a n impact on the U.S. and South Vietnam. The South Vietnamese people were caught between communists and the Viet Cong of North Vietnam. Their government and their lives depended on how this war went. And at home, Americans lost confidence in what their leaders were telling them, as their assurance in their own government officials was seriously eroded.

After Tet, (CBS Evening News anchorman) Walter Cronkite, who was called “the most trusted man in America,” at that time, told his viewers, “We’re not going to be able to win,” and that our best hope would be to “negotiate our way out.”

Shortly after, LBJ announced on TV that he would not seek re-election for the Presidency.

Cronkite’s comment was a remarkable thing, but he felt betrayed, like he had been used by American officials. He had been a war correspondent during World War II. He went to Vietnam and came back with his own opinion. His statement (of those opinions on air) was a real departure for a journalist back then, but he felt compelled.

The U.S. had fought in World War II and Korea, but Vietnam was a real blow to that essentially naïve belief that our sheer military strength would prevail, no matter what. Sometimes we go tto war for really bad reasons, and we’re told lies. We’re betrayed by our own government.

Westie continued to have this fixed idea, and did not waiver, in his belief that Hue was not a serious setback.

Hue 1968 is described as your “most ambitious work yet,” and the research you’ve done is amazing. How long did it take to put this book together, and how did you trace all of this history, and in such detail?

It was a very ambitious undertaking. Throughout my career, I’ve always looked for projects with bigger, harder challenges. The nature of journalism is plunging into subject about which you know nothing.

Because of the internet, I learned about finding American soldiers who had fought in Vietnam. Once I could find one or two, I would get an “interview tree” to branch out on. Finding soldiers from the Vietnamese side was different. I realized I needed to hire people who were really good at finding people, and work with them and through them…to find Vietnamese veterans…then I followed up.

I did the traditional things you have to do to be a serious historian. But I am not an academic historian and don’t pretend to be. I visited the LBJ (Presidential) Library in Austin, Texas. I studied Westmoreland’s papers.

My book is based on interviews and memories of people who were there. There are advantages and disadvantages to that–memories are not perfect, but I feel justified in relying on memory. I’ve received unsolicited e-mails of thank from people, for capturing what others did not in this story. A sweet spot for me in the timing of the book is that people are still alive who lived it.

The book took six years. The first steps toward working on this book took place years ago. I began ordering books on the subject, thinking how to go about it. The process is 99% research and reporting in the beginning, then 50/50 reporting/writing, and then 99% writing.

Who should read this book? How can young people today relate to this event, and why is it important for today’s generation to know about this?

It goes to the question of “Why study history?” It has a lot to tell us about successes and failures and how things happen they way they do. I can’t imagine anything more important. It delves into motivation–and mistakes made. As a society, not as individuals, we see how Vietnam has reverberations still today, in its effects on society. It’s a way to continue that good hard look at how we fit in that coherent flow of history.

I would hope that everyone should read this book. It’s not just for a military audience or academic historians. And for all those reasons, it’s a compelling story.

Do you have family or other connections to Vietnam and to this war?

No connections. None of my brothers served in Vietnam. I had some uncles who served in Korea and World War II. No cousins. I knew people in high school and college and throughout my life who served in Vietnam. I grew up living with the Vietnam war in my house and arguing with my dad about it.

Is it true that Hue 1968 will be produced as a television mini-series?

It’s already in the works. It’s set to be a 10-part mini-series on FX, with Michael Mann as the producer/director. That work is just beginning. I’m excited about it!

Mark Bowden

What’s your next writing project/book?

I have the cover story on The Atlantic this month (on what to do about North Korea). A Vanity Fair story. I kind of deliberately don’t have a book project now. I like to have time in between books. But ask me again at the end of the year!

Hue 1968 is Lemuria’s August selection for its First Editions Club. Mark Bowden will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival first at 12:00 in the Old Supreme Court Room with Howard Bahr, author and Vietnam veteran. He will also be interviewed with U.S. Representative Trent Kelly at 4:00 in State Capitol Room 201H about the Vietnam War.

In 2003, I had an idea to write a book about one dramatic afternoon at the 1956 Democratic convention when Kennedy challenged the party establishment and nearly became the vice presidential nominee after Adlai Stevenson asked the delegates to choose his running mate. Even though he lost, Kennedy emerged as a new political star. As a teenager watching the struggle on TV, I had been fascinated. It was the last time any convention has gone past a first ballot.

In 2003, I had an idea to write a book about one dramatic afternoon at the 1956 Democratic convention when Kennedy challenged the party establishment and nearly became the vice presidential nominee after Adlai Stevenson asked the delegates to choose his running mate. Even though he lost, Kennedy emerged as a new political star. As a teenager watching the struggle on TV, I had been fascinated. It was the last time any convention has gone past a first ballot. China Miéville’s

China Miéville’s  “I wanted to reconcile my profound love of the South with a deep anger that boiled in me when I confronted our peculiar history,” he writes in his newest book,

“I wanted to reconcile my profound love of the South with a deep anger that boiled in me when I confronted our peculiar history,” he writes in his newest book,

These qualities lie at the heart of an outstanding new work,

These qualities lie at the heart of an outstanding new work,

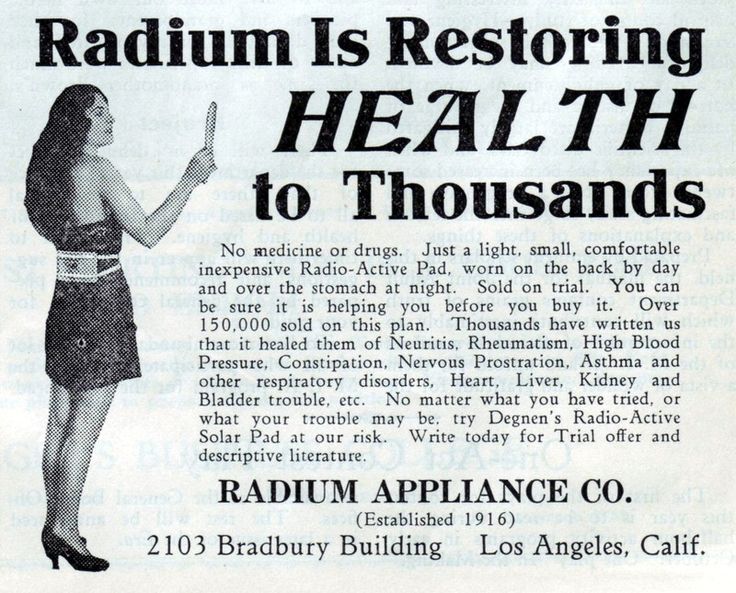

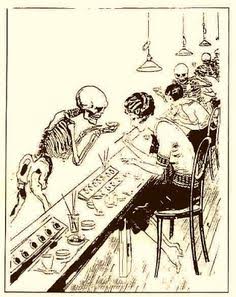

Most, if not all, of the girls who worked for USRC started getting ill. Some had sore mouths, some had achy joints, some started walking with limps, and some showed all of the symptoms. Several of the women developed deadly sarcomas. Since radium affected each girl differently, the sources of their illness were misdiagnosed. Syphilis, “phossy jaw,” early onset arthritis, etc. were some of the main diagnoses. These “radium girls” were dying left and right, and USRC kept denying that their deaths were work-related. Finally, with the help of sympathetic doctors and committee agents, radium was finally pinpointed as the cause of these deaths and illnesses.

Most, if not all, of the girls who worked for USRC started getting ill. Some had sore mouths, some had achy joints, some started walking with limps, and some showed all of the symptoms. Several of the women developed deadly sarcomas. Since radium affected each girl differently, the sources of their illness were misdiagnosed. Syphilis, “phossy jaw,” early onset arthritis, etc. were some of the main diagnoses. These “radium girls” were dying left and right, and USRC kept denying that their deaths were work-related. Finally, with the help of sympathetic doctors and committee agents, radium was finally pinpointed as the cause of these deaths and illnesses. Jimmy Buffett is at the center of my musical taste, from way back when I was but a tiny child riding in the back seat of my mom’s Camaro. He’s known for his

Jimmy Buffett is at the center of my musical taste, from way back when I was but a tiny child riding in the back seat of my mom’s Camaro. He’s known for his

I’ve seen this book lurking around the store since I arrived here two years ago, but only felt compelled to pick it up due to the impending arrival of David Grann, who was here last week to promote his new book, Killers of the Flower Moon. Boy, am I glad I finally discovered The Lost City of Z…well, discovered the book anyway. It tells the captivating tale of Col. Percy Fawcett, a British explorer from the Royal Geographic Society who first comes to South America in search of adventure, and later becomes obsessed with finding a mythical city, representing for Percy the soul of the Amazon itself. This is the most captivating mystery in the jungle I’ve heard about since the television show Lost went off the air. Grann’s book is about obsession, history, geography, and the limits of what humans can ever empirically know. I cannot recommend this book highly enough.

I’ve seen this book lurking around the store since I arrived here two years ago, but only felt compelled to pick it up due to the impending arrival of David Grann, who was here last week to promote his new book, Killers of the Flower Moon. Boy, am I glad I finally discovered The Lost City of Z…well, discovered the book anyway. It tells the captivating tale of Col. Percy Fawcett, a British explorer from the Royal Geographic Society who first comes to South America in search of adventure, and later becomes obsessed with finding a mythical city, representing for Percy the soul of the Amazon itself. This is the most captivating mystery in the jungle I’ve heard about since the television show Lost went off the air. Grann’s book is about obsession, history, geography, and the limits of what humans can ever empirically know. I cannot recommend this book highly enough. The Osage tribe in the late 1800s, like many other native peoples of the Americas, had been confined to smaller and smaller territories as white settlers hungered for their land. After seeing

The Osage tribe in the late 1800s, like many other native peoples of the Americas, had been confined to smaller and smaller territories as white settlers hungered for their land. After seeing

With Candice Millard’s latest biography

With Candice Millard’s latest biography  So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed

So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed The Great Beanie Baby Bubble

The Great Beanie Baby Bubble Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans

Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of Elements

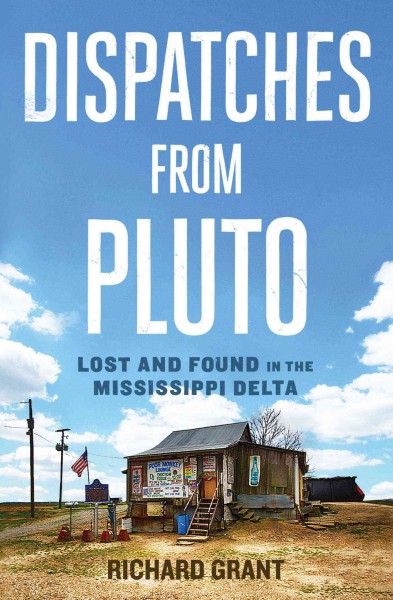

The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of Elements Dispatches from Pluto: Lost and Found in the Mississippi Delta

Dispatches from Pluto: Lost and Found in the Mississippi Delta