Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (April 7)

In her latest novel, Lost and Wanted, Nell Freudenberger’s admitted “language brain” delves deeply into the world of science, as complicated theories meet complicated characters–both of whom merit the time and curiosity of an intense examination.

In her latest novel, Lost and Wanted, Nell Freudenberger’s admitted “language brain” delves deeply into the world of science, as complicated theories meet complicated characters–both of whom merit the time and curiosity of an intense examination.

Named one of The New Yorker‘s “20 Under 40” nearly a decade ago, Freudenberger is one author whose career continues to shine, collecting an impressive array of awards along the way.

As the author of novels The Newlyweds and The Dissident and the story collection Lucky Girls (which was awarded the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction afrom the American Academy of Arts and Letters), Freudenberger has also captured a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Whitling Award, and a Cullman Fellowship from the New York Public Library.

She and her family make their home in Brooklyn.

In a book as much about relationships as science, Lost and Wanted tugs at heartstrings even as it posits scientific theories of Nobel Prize level. To set the stage, please tell us briefly about main characters Helen, Charlie, Terrance, and Neel.

Helen is a theoretical physicist at MIT, who had a baby on her own in her late 30s. Her primary relationships are with her son, Jack, and with her work, which she loves–maybe too much to get close to anyone else.

Her college friend, Charlie, is similarly driven in her own field, but they’ve faced different challenges as a white scientist in academia and a black screenwriter in Hollywood. Charlie is one of those people who is magnetic and wonderful in person, but elusive as soon as you leave her side. When she dies suddenly, from complications of lupus, Helen doesn’t have a chance to say goodbye.

She seeks out Charlie’s daughter and husband, Terrence, in an attempt to understand more about her friend’s death. Terrence is reserved and hard to read; with his brother, he runs a Los Angeles-based surf shop, and he and Helen seem to have little in common–except that they’re suddenly both single parents, grieving for the same person. Just as they’re starting to trust each other, Helen’s charming and emotionally clueless ex, Neel, drops two bombshells–one personal and one scientific–and Helen’s carefully organized existence starts to fall apart in ways that challenge her most closely held beliefs.

The depth of your use of science knowledge and theory is impressive! What inspired you to write this story of advanced theories about “five-dimensional spacetime” and cutting-edge discoveries about the mind, the brain, gravitational force–and the possibility of ghosts?

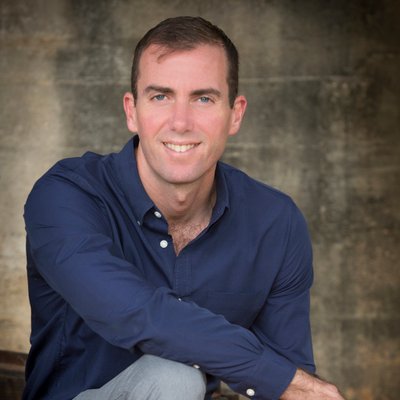

Nell Freudenberger

I knew that I wanted to write a book about women and work, and at first, I tried to play it safe; I made Helen a novelist. That didn’t work at all, maybe because I couldn’t get out of my own head enough to find her voice. I thought I might make one of the minor characters an astrophysicist, and so I started reading an introductory college level textbook that a friend recommended. I don’t have a science background, and I was intimidated, in part because I’d always been told that I was a “language person” or that I didn’t have a “math brain.”

One book led to another, though, and I found that I was fascinated by particular topics, especially the gravitational wave detection project known as LIGO. I thought it was incredible that Einstein had theorized these “ripples in the fabric of spacetime,” but never believed human beings would be able to detect them, and that almost exactly 100 years later, scientists were doing just that.

My interest led me to cold e-mail some physicists, who were extremely kind. They spent hours explaining their work to me and showing me the lab that appears in the book. Their passion to communicate what they knew–for no reason other than the pleasure they took in it–was the real spark for Helen’s character, and convinced me that I could learn enough to make Helen believable as a physicist.

As for ghosts, I don’t believe in them–most of the time. None of the physicists I met told me that they did either, but they did often subscribe to counter-intuitive theories about space, physical forces, or the origins of the universe. Like Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, their explanations of physical phenomena had to be taken on faith or derived mathematically; they didn’t make sense inside a human being’s three-dimensional experience of the world. Talking to physicists about these wild ideas stretched my own capacity for belief.

Please tell me about the poem read at Charlie’s funeral–and explain how that became the title of the book.

The untitled poem by Auden that begins “This lunar beauty…” made a deep impression on me when I was an undergradate. Some people in our seminar thought the poem was about death; our professor insisted it was about pregnancy–his wife was about to have a baby; others argued that it was just a poem about the moon. To me, that indeterminacy was what made the poem so beautiful, and spoke to our different conceptions of an afterlife.

Those metrically regular and perfectly rhymed lines–“Where ghost has haunted/Lost and wanted”–gave me a natural title for the book. They seemed to suggest an interim pace that was more mathematical than purgatorial, maybe even a digital space somewhere between life and death.

Tell me about the meaning of “unseen communication”–a phrase that is referenced several times in Lost and Wanted. Does it hold more than one meaning among the characters and their discoveries about life, love, grief, acceptance, and unknown mysteries of the universe?

Science is never finished, and I love the physicist John Wheeler’s idea that each generation suggests a paradox for the next to solve. That’s one kind of “unfinished communication” that appears in the book; another is the mistaken belief that we’ll always have time to say the things we want to say to the people we love.

When a relationship ends–in death or another kind of rupture–we sometimes panic or become depressed about what we wish we’d said while there was still time. Technology now complicates this equation, because we all leave digital records behind, rarely as neatly as we’d like. Sometimes the presence of this stray information make it even more difficult to believe that the loved one is really gone.

For the children in the book, whose experience of time is more abstract than that of their counterparts, there’s a very real sense that it may still be possible to communicate with the people they’ve lost, if only they can find the right medium.

What are we to make of Charlie’s apparent attempts to communicate with her loved ones even after her death, as is demonstrated in the final pages of the book?

I’ll let you make what you will of that!

Nell Freudenberger will be at Lemuria on Friday, April 12, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss Lost and Wanted.

I once heard that suspense in a work of fiction should feel like watching a balloon expand steadily. Each detail, each new turn or development in the plot should function like another breath going in, applying another ounce of pressure as the skin swells and grows taut until at last it reaches the breaking point.

I once heard that suspense in a work of fiction should feel like watching a balloon expand steadily. Each detail, each new turn or development in the plot should function like another breath going in, applying another ounce of pressure as the skin swells and grows taut until at last it reaches the breaking point.

New Orleans native Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s debut novel is a darkly thought-provoking satire on race in America that is based on one African-American man’s plan to spare his teenage son from racial disparities he and his own father have endured–thanks to a new medical procedure that can change his biracial son’s skin white.

New Orleans native Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s debut novel is a darkly thought-provoking satire on race in America that is based on one African-American man’s plan to spare his teenage son from racial disparities he and his own father have endured–thanks to a new medical procedure that can change his biracial son’s skin white.

Valeria Luiselli’s newest novel,

Valeria Luiselli’s newest novel,

I was very excited to see a family tree in the first few pages. From Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to Yaa Gyasi’s

I was very excited to see a family tree in the first few pages. From Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to Yaa Gyasi’s