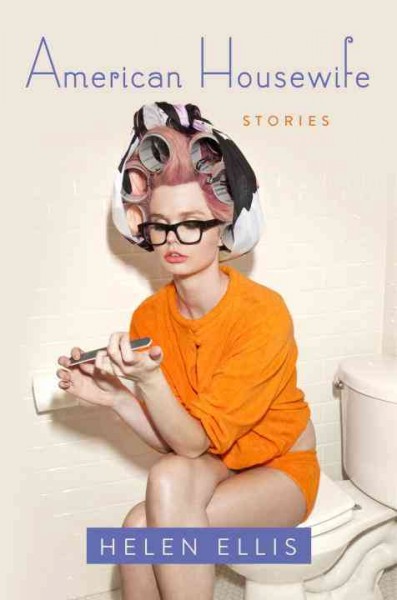

I have to bake cookies for the board, so I’ll leave the blood for later.

I am rendered a bit speechless in trying to describe what makes Helen Ellis’s new collection of short stories, American Housewife, so sharp and delectable. It is an homage of sorts (equal parts tender and piercing) to the oft-scoffed at domesticity that some women have chosen to take up, despite so many loud voices claiming that staying home is synonymous with giving up.

I am rendered a bit speechless in trying to describe what makes Helen Ellis’s new collection of short stories, American Housewife, so sharp and delectable. It is an homage of sorts (equal parts tender and piercing) to the oft-scoffed at domesticity that some women have chosen to take up, despite so many loud voices claiming that staying home is synonymous with giving up.

The settings are so familiar, just women doing simple hausfrau things like introducing new book club members to a circle of readers, supporting young and burgeoning artists, or gossiping with the bellboys about building residents. And then,

AND THEN,

The dynamic shifts, ever so subtly, and there is an itch in the back of your brain telling you that something about all of this is strange. Sometimes, that feeling is because there is definitely a dead body somewhere in the apartment. Sometimes, it is because the women in several of these stories full of vacuuming and meal planning are happy. Not a cynical, eye-rolling “happy”, but truly content. (What does it say about us as readers that when reading a story about a housewife, we expect to be thrilled by some outside catalyst- as if a story simply about a woman in her home could never be truly enough?) In a sparse, two page story titled “What I Do All Day”, the narrator wakes up, makes coffee, throws a party, and goes to bed flawed and at peace.

I see everyone out and face the cold hard truth that no one will ever load my dishwasher right. I scroll through iPhone photos and see that if I delete pictures of myself with a double chin, I will erase all proof of my glorious life. I fix myself a hot chocolate because it is a gateway drug to reading. I think I couldn’t love my husband more, and then he vacuums all the glitter.

Not all of the stories in this collection are home runs (very, very few collections can boast such a thing), and at times the narratives drag just the tiniest bit; but the parts of this book that shine are absolutely stunning. In “Hello! Welcome to Book Club”, the needling feeling of dread that came from the slowly unfolding purpose of said book club was thrilling, to say the least.

The women in American Housewife are forces to be reckoned with. They bake, they plan parties, they are patrons of the arts, they grocery shop, they murder building committee members, and then they clean up the blood with organic, non-toxic kitchen sprays. Their experiences range from the every day to the utterly extraordinary and bizarre, and I cannot stop thinking about them. That is, I suppose, one of the best things you can say about a book.

Well folks, I just finished my favorite literary adventure of 2015 with Homer Hickam, Jr.’s new novel,

Well folks, I just finished my favorite literary adventure of 2015 with Homer Hickam, Jr.’s new novel,

China Miéville’s newest work,

China Miéville’s newest work,

For the first time in a while, certainly all year, I am unsure of what to make of a book.

For the first time in a while, certainly all year, I am unsure of what to make of a book.

This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about

This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about

So I don’t think I will win over many people by saying that

So I don’t think I will win over many people by saying that