By Lovejoy Boteler. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (June 2)

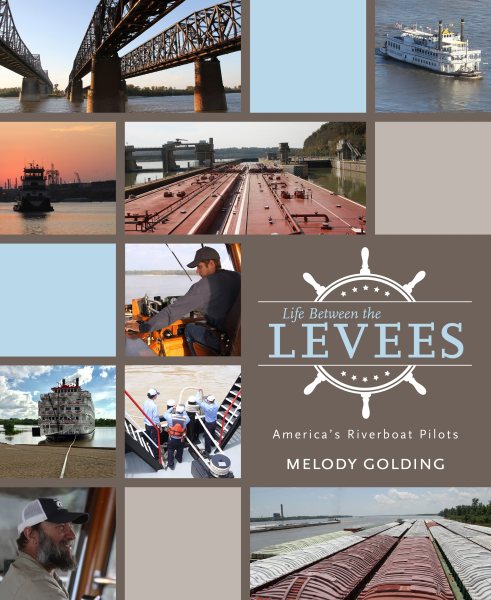

One summer in my twenties I worked as a deckhand on the Greenville, a towboat that plied the upper Mississippi River from Alton, Illinois to Davenport, Iowa. In that short span of time I came to understand the tremendous power of the river and the importance of its commerce. Melody Golding’s superb book, Life Between the Levees: America’s Riverboat Pilots, with its countless tales of adventure and antics on “brown water” transported me straight back to that time.

One summer in my twenties I worked as a deckhand on the Greenville, a towboat that plied the upper Mississippi River from Alton, Illinois to Davenport, Iowa. In that short span of time I came to understand the tremendous power of the river and the importance of its commerce. Melody Golding’s superb book, Life Between the Levees: America’s Riverboat Pilots, with its countless tales of adventure and antics on “brown water” transported me straight back to that time.

Golding is uniquely qualified to have compiled Life Between the Levees. She states in the first line of the introduction, “I come from a river family.” With that simple but powerful statement, she hints at the soul of the river as it can only be revealed by the folks who have an intimate connection with that life. Her deep love for the river comes through, and must have fueled her passion to create this comprehensive work. She has given us a book with beautiful documentary photographs, both personal and archival, and authentic stories told by colorful characters, many of whom she has known.

For ten years, with single-minded purpose, Golding of Vicksburg traveled thousands of miles on the Mississippi and its inland waterways to record over one hundred voices and stories of brown water mariners: steely-eyed captains, pilots, deckhands, cooks, and chaplains, some of whom have now passed from the scene. Her interviews reveal events that occurred over a seventy-year span of time. Older captains who were trained by the legendary pilots of the great paddle wheelers of the nineteenth century provide poignant, provocative and sometimes hilarious insights. Life Between the Levees: America’s Riverboat Pilots captures a slice of history that is destined to become an important and lasting part of American folklore.

Sometime the call of the river came at an early age. Joy Mary Manthey, from Louisiana, remembers steering a towboat as a young girl. “I had to stand on the milk crate to see over the wheel, and I steered the boat. I loved it. I mean…I was only ten years old.” After some interesting life adventures, Joy Mary became a nun, and then a towboat chaplain.

Perry Wolfe remembered his first experience on the river as a young boy. His dad called him “his first mate.” He slept on sandbars. Perry soon realized that his life would forever be on the river. He would eventually become a deckhand with Brent Towing, out of Greenville and talked about how life on the river was in the old days. “Actually up there at Lock 26, it was more wild than Natchez Under the Hill … being a captain back then was a lot harder because you had to referee all the fights.”

Captain William Torner, on old-timer, recalled the steamboats of yesteryear. “I am one of the few river men still living who has worked on a steamboat built in the 1800s”. In 1940 Captain Torner worked on the Reliance out of Pittsburgh.

The Mississippi River and its tributaries have influenced the shape of the collective psyche of America through Mark Twain’s tales of Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer, and now with Melody Golding’s seminal book, the voices of modern-day captains and crews.

The river is a place where a person can find peace. Patrick Soileau, thirty years on the waterways summed it up. “…it’s your time for solitude…I could probably solve the world’s problems up here.”

In Life Between the Levees: America’s Riverboat Pilots, through captivating interviews, Melody Golding chronicles stories of hope and pathos, friendship and sometimes disaster, away from the bustling world of landlubbers. Life Between the Levees is a book to be savored and enjoyed for years to come.

Lovejoy Boteler is author of Crooked Snake: The Life and Crimes of Albert Lepard published by University Press of Mississippi. He lives in Jackson.

Melody Golding will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival August 17 as a participant in the “Mississippi: The Delta” panel at 9:30 a.m. at the State Capitol Room 201 A.

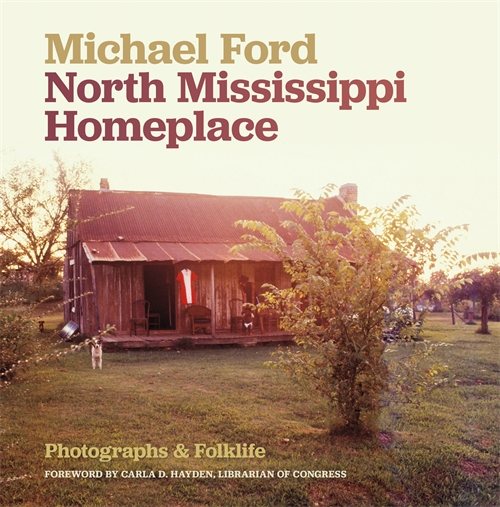

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

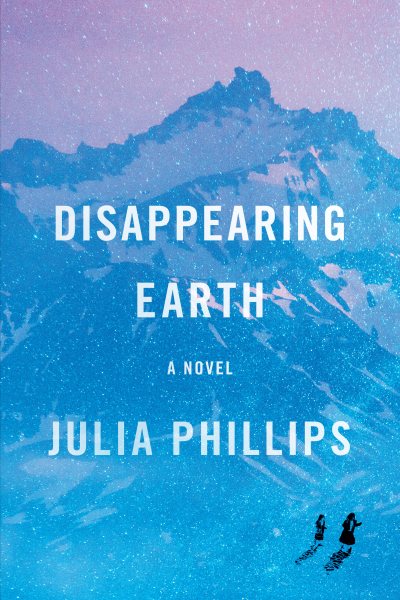

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

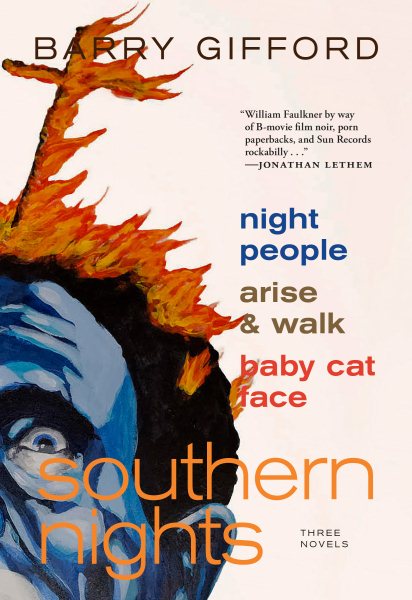

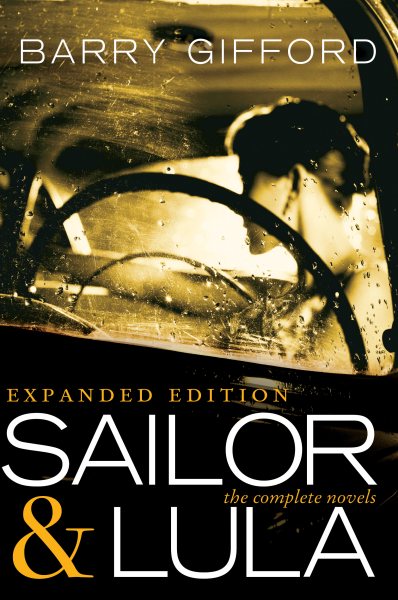

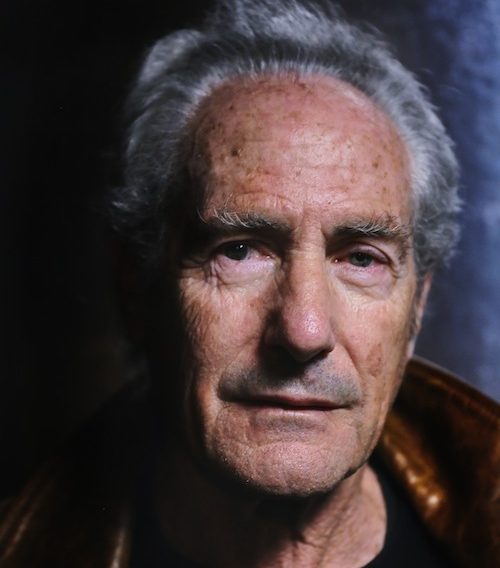

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing.

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing. “My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

“My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

Oxford’s Mary Miller highlights a Mississippi coastal town with a thoughtful tale of a middle-aged man facing an uncertain and lonely future–until he adopts a dog on a whim and one thing leads to another.

Oxford’s Mary Miller highlights a Mississippi coastal town with a thoughtful tale of a middle-aged man facing an uncertain and lonely future–until he adopts a dog on a whim and one thing leads to another.

Casey Cep in

Casey Cep in  And yet. As Hungary and the citizens of the Engels’ town of Pecs, Hungary were overrun by Nazi forces in 1944, a century of prominence, good works and assumed assimilation weren’t enough for the Engels. The scion of the Pecs branch of the family—McMullan’s grandfather’s first cousin Richard Engel—died at the Mauthausen concentration camp after being rounded up along with other town Jews in March 1944. The story of Richard’s descent from respected, wealthy World War I war hero and city civic leader to being marched off as townspeople watched is the spellbinding story that McMullan tells in

And yet. As Hungary and the citizens of the Engels’ town of Pecs, Hungary were overrun by Nazi forces in 1944, a century of prominence, good works and assumed assimilation weren’t enough for the Engels. The scion of the Pecs branch of the family—McMullan’s grandfather’s first cousin Richard Engel—died at the Mauthausen concentration camp after being rounded up along with other town Jews in March 1944. The story of Richard’s descent from respected, wealthy World War I war hero and city civic leader to being marched off as townspeople watched is the spellbinding story that McMullan tells in

This is what bestselling author and Alabama native Helen Ellis calls “

This is what bestselling author and Alabama native Helen Ellis calls “