Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (October 27)

If you haven’t given much thought to the American Civil War lately, bestselling author and Pulitzer Prize finalist S. C Gwynne offers some compelling thoughts on the country’s current state of division as he examines–in depth–the fourth and final year of the War Between the States.

If you haven’t given much thought to the American Civil War lately, bestselling author and Pulitzer Prize finalist S. C Gwynne offers some compelling thoughts on the country’s current state of division as he examines–in depth–the fourth and final year of the War Between the States.

Hymns of the Republic: The Story of the Final Year of the American Civil War chronicles the events, people and politics of the U.S. in 1864–a time when almost no one, including Abraham Lincoln himself, thought the president would win re-election. The book traces the rough roads Union General Ulysses S. Grant and his counterpart Robert E. Lee traveled as each drove toward victory; the triumphs of nurse Clara Barton; the role that 180,000 black solders forged as they donned Union uniforms, Lee’s ultimate surrender at Appomattox; and finally, the assassination of Lincoln.

Gwynne’s previous books include the award winning Empire of the Summer Moon, Rebel Yell, and The Perfect Pass. As a former journalistic, he served as bureau chief and national correspondent with Time and as executive editor for Texas Magazine, among others.

Today he and his wife, the artist Katie Maratta, live in Austin, Texas.

Hymns of the Republic begins with Washington D.C.’s 1863-64 winter “social season” in high gear as the Civil War dragged on–and the nation’s leaders were given an infusion of hope when Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general over the Union forces. Please explain what that meant to Washington and the war effort.

S.C. Gwynne

When Grant arrived in Washington, he inspired a hopeful, almost joyful feeling in the North that the war might soon be over. Here was the great and glorious warrior from the “west,” victor of Shiloh, Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. Here, at last, was someone to challenge the great Robert E. Lee.

What happened next was the opposite of hope and joy. Within a few months of Grant’s arrival, he and Lee would unleash a storm of blood and death that beggared even the killing fields of Gettysburg and Chancellorsville. And there would be no great northern victory. It was, in fact, Grant’s failure to beat Lee–which opened the large possibility that Abraham Lincoln might not re-elected–that really set the stage for the war’s dramatic final act.

The next presidential election lay ahead, and it seems that Lincoln himself had doubts that he would win. Potentially, what could his loss in the election have meant for the war’s outcome?

In the summer of 1864, it was hard to find anyone in the country, North or South, Republican or Democrat, including Lincoln himself, who believed the president would be re-elected. If he had lost, I believe there would almost certainly have been some sort of negotiated peace, probably with slavery intact in the South. The Civil War would still have to be fought to a close–because the fundamental issue that had caused it in the first place, whether the new territories and states would be slave or free, had not been resolved–but that final action would have been delayed by many years. That’s just my opinion.

Tell me briefly about the contributions that former slaves made to the Union efforts in the war.

Most people have lost track of this, but 180,000 black soldiers fought for the North in the Civil War, most of them in the final year. Some 60 percent of them were former slaves. This meant that men who had been held in bondage one month–without any legal rights, including the right to marry, to hold assets, to buy real estate, to use the courts to settle grievances, to travel, to hold a job–were suddenly wearing uniforms. They had jobs. They earned salaries. They had weapons. Their numbers, and their success as fighters, did much to tip the scales in favor of the Union.

If you look at troop strength, North and South, it always seems as though the Union has a large advantage. But because the North was trying to hold and control so much real estate, as well as garrison Southern cities and protect its supply lines, its advantage on the battlefield was less than it seemed. Black soldiers amounted to an astounding 10 percent of the Union army.

Briefly explain the comparisons you draw between Lincoln and Confederacy President Jefferson Davis as the war was coming to a close.

The two men were so radically different. They shared traits of stubbornness and deep conviction, but otherwise came from different planets. Lincoln was kind, tolerant, forgiving, and personally warm. Davis was brittle, unforgiving, thin-skinned, and grudge-holding. His public persona was often stiff, cold, and unemotional. Both men arguably held their countries together because of their unwillingness to compromise. Lincoln insisted on full restoration of the Union and the abolition of slavery as his basic terms for peace. Davis insisted on the full sovereignty of the southern nation.

Your book examines that last year of the U.S. Civil War in a great deal of detail. What lessons does this documentary of that period hold for Americans today–and why should we still be considering the history of the Civil War today?

The most basic lesson is that the United States of America is, and always has been, a deeply divided country. In the Civil War it was divided by region, state, and race. It still is.

Look at a map of red and blue state America. Read any newspaper to see the often-bitter national debate on race. The Civil War, in which 750,000 people died and huge sections of the South were destroyed, was this divide at its most extreme.

As grim as those statistics are, you can look at the history that followed as the United States somehow muddled through. We are no longer killing ourselves at the rate we did in 1864. Our democracy is messy and imperfect. We are still muddling. Today I read in the paper that the president of the United States in October 2019 was predicting a Civil War. But I draw some small hope from my reading of history.

S.C. Gwynne will be at Lemuria on Monday, October 28, at 5:00 to sign and discuss Hymns of the Republic, in conversation with Donald Miller. Lemuria has selected Hymns of the Republic its November 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

Some people make their own luck. Others have never met a stranger. In the case of lifelong Jacksonian Bill Morris, these notions work in tandem. As the founder of the William Morris Group, Bill has made a name for himself nationally in the insurance world. However in his memoir,

Some people make their own luck. Others have never met a stranger. In the case of lifelong Jacksonian Bill Morris, these notions work in tandem. As the founder of the William Morris Group, Bill has made a name for himself nationally in the insurance world. However in his memoir,  It is the global projection of this image, as imperfect as it may be in actuality, that has long been a part of the lore and lure of the United States of America. It is the mirage that entices thousands upon thousands of people to leave their troubled homelands and, sometimes, risk their lives to come to “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” where they are free to live their lives as they see fit, worship the God of their choice, and consume as much as their wallet will allow.

It is the global projection of this image, as imperfect as it may be in actuality, that has long been a part of the lore and lure of the United States of America. It is the mirage that entices thousands upon thousands of people to leave their troubled homelands and, sometimes, risk their lives to come to “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” where they are free to live their lives as they see fit, worship the God of their choice, and consume as much as their wallet will allow. O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist.

O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist. If you are already charmed—and simultaneously put off—by Olive Kitteridge of Crosby, Maine, welcome back. If you’re new to Elizabeth Strout’s expertly crafted small-town characters who face the same challenges as the rest of us, we’ve been waiting for you. Elizabeth Strout has released a sequel to her beloved book in this year’s

If you are already charmed—and simultaneously put off—by Olive Kitteridge of Crosby, Maine, welcome back. If you’re new to Elizabeth Strout’s expertly crafted small-town characters who face the same challenges as the rest of us, we’ve been waiting for you. Elizabeth Strout has released a sequel to her beloved book in this year’s  The resulting book from this author, photographer and artist is

The resulting book from this author, photographer and artist is

Stories From 125 Years of Ole Miss Football

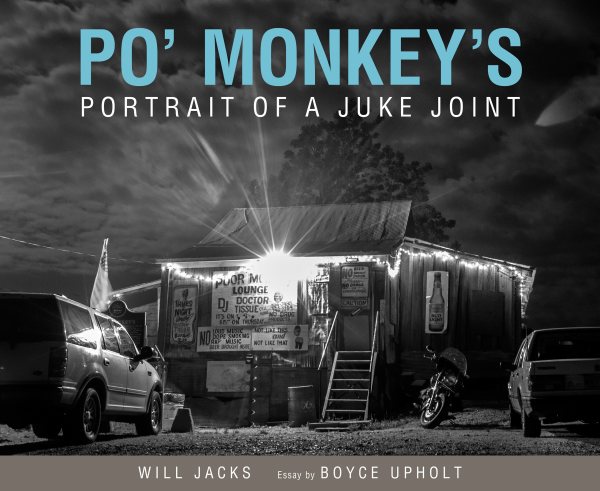

Stories From 125 Years of Ole Miss Football Mississippi Delta photographer and documentarian Will Jacks celebrates the life and times of the late Willie Seaberry, owner of Po’ Monkey’s blues house in Merigold for more than 50 years, in

Mississippi Delta photographer and documentarian Will Jacks celebrates the life and times of the late Willie Seaberry, owner of Po’ Monkey’s blues house in Merigold for more than 50 years, in