Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (October 15)

Beth Ann Fennelly, poet laureate of Mississippi, once again stretches her literary abilities with a new release she calls “a true hybrid.”

The Oxford author who has netted a considerable number of writing awards and accolades as a poet and novelist captures the attention of readers in a fresh, new approach with Heating and Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs, with entries that range from one sentence to five pages.

The micro-memoir, she has said, “combines the extreme abbreviation of poetry, the narrative tension of fiction, and the truth-telling of creative nonfiction,” in works that include “memories, quirky observations, tiny scenes, (and) bits of overheard conversations that, with the surrounding noise edited out, reverberate.”

The micro-memoir, she has said, “combines the extreme abbreviation of poetry, the narrative tension of fiction, and the truth-telling of creative nonfiction,” in works that include “memories, quirky observations, tiny scenes, (and) bits of overheard conversations that, with the surrounding noise edited out, reverberate.”

Writing micro-memoirs, she said, was “liberating” after she had co-authored The Tilted World, a novel that required extensive research, with her husband Tom Franklin. “After living in the heads of characters, now my own thoughts, my own experiences, seemed newly fresh,” she said.

Additionally, Fennelly has published three poetry books: Open House, Tender Hooks, and Unmentionables, and a book of nonfiction Great with Child. She’s won grants from the Mississippi Arts Commission (three times), the National Endowment for the Arts, the United States Artists, and a Fulbright to Brazil. Her work has won a Pushcart Prize and was included three times in The Best American Poetry Series. She was also the first woman to claim the University of Notre Dame Alumni Association’s Griffin Award for Outstanding Accomplishments in Writing.

Growing up in a suburb of Chicago, Fennelly said her first love was poetry, which she studied at the University of Notre Dame, earning first a bachelor’s degree magna cum laude in 1993; and a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Arkansas in 1998.

An English professor in the MFA program at the University of Mississippi, Fennelly has been named Outstanding Teacher of the Year. She and Franklin, also an English professor at Ole Miss, are the parents of three children.

At what point in your life did you discover that you were a writer?

I was always an artistic kid, loving the theater and music and reading and writing, but I didn’t know I wanted to be a writer until I got to college. That’s where I experienced my first truly great teachers and was exposed to contemporary poetry. In my high school, we only read the classics. I think that’s one reason why I take my job as a college professor so seriously–I know how an engaged teacher can turn a student’s life around.

Poetry is a different kind of writer’s challenge. How were you drawn to poetry?

Beth Ann Fennelly

I was drawn to the dynamic compression of poetry, almost like a chemical reaction–how can so few words trigger such a big response? Also, I was, and still am, in love with the sound of words, their mouth-feel, as wine enthusiasts say. It’s a huge pleasure to take a poem into your body through memorization and release it back into the world with the air that rises from your windpipe.

Your newest book is a nonfiction collection of brief personal thoughts, idea, and memories, along with several short essays. They deal with family, marriage, fears, triumphs, nostalgia, and hopes. Was this a collection you have gathered through the years, or did you write these specifically to be published as a book?

Before I published this book, my husband and I wrote a collaborative novel. Called The Tilted World (HarperCollins, 2013), it was set in the flood of the Mississippi River in 1927, and it ended up being a big project. Although we’d each published four books, we’d never written one together. In addition to teaching ourselves how to collaborate, we had to do a lot of research. And it was high stakes: We spent four years writing the novel. Imagine, if it failed, how costly that would have been for our marriage.

Luckily, it didn’t fail. After we returned from our book tour, tuckered, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to write next. There followed a long, frustrating, fallow period in which I wasn’t writing. I mean, sure, I was scribbling little thoughts and ideas in my notebook, but nothing was adding up to anything. Many of my scribbles were just sentences, or a paragraph, the longest just a few pages. I kept complaining to my patient husband that I was “not writing.”

Eventually, however, it occurred to me that I was enjoying this scribbling in my notebook. After the high stakes, research-heavy, character-embedded-thinking of the novel, my own life seemed rich material again. The little memories or quirky thoughts or miniature scenes I was creating seemed refreshing.

So, strangely, I identified the feeling of writing before I identified the activity. I thought, “What if this ‘not writing’ I’m doing actually is writing, and I just don’t recognize it because it doesn’t look like other writing I’ve done? What if I need to stop waiting for these things to add up to something, and realize maybe they already are somethings, just small? Once I’d recognized the form and gave it a name, the micro-memoir, I realized I was almost done with a book.

Today, you and Tom are professors in the English department at Ole Miss, where you teach poetry and nonfiction writing–and where you have been named Humanities Teacher of the Year and College of Liberal Arts Teacher of the Year. What do you enjoy most about being a teacher?

I really like working with young adults–I think they keep me young in certain ways, because I’m always getting exposed to new ideas. I love the feeling of being in love with a book or an author, and not just conveying my own passion, but kindling that same passion in my students.

Books have been such important companions to me, and reading has schooled me in empathy and reflection. These are skills the world isn’t encouraging in our young people. I’m honored that I get the chance to share the transformative power of literature with them.

In 2016, you were named poet laureate for the state of Mississippi. What are your duties that go along with that?

I’ve just finished the first year of my four-year term, and I’ve had a blast. I’m interested in getting poetry in front of as many Mississippians as possible, especially children. The position is honorary in that there’s no salary involved, and therefore my “duties” are probably more “suggestions,” but I’m traveling to a lot of libraries and schools, and I’m deeply involved in our state’s Poetry Out Loud program, which I think every high schooler should be a part of.

Beth Ann Fennelly will be at Lemuria on Thursday, November 9, to sign and read from Heating and Cooling. The signing will begin at 5:00 p.m. and the reading will begin at 5:30.

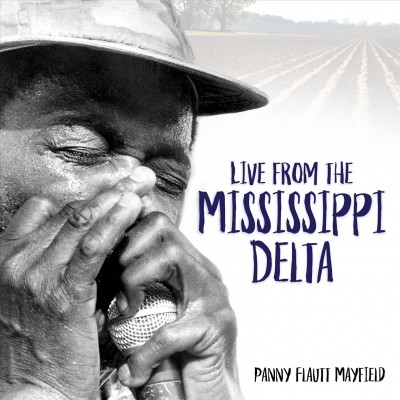

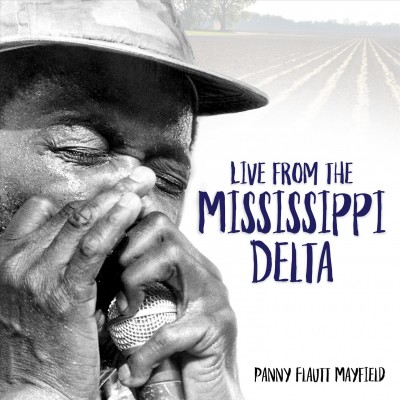

While the Coahoma County seat may not be a booming metropolis, the camera-wielding Mayfield frequently found herself in the right place at the right time, during culturally significant events and times over the past 30 years. Her casual stream-of-consciousness photo journal lets the reader in on the energy, with the perspective only a local could provide.

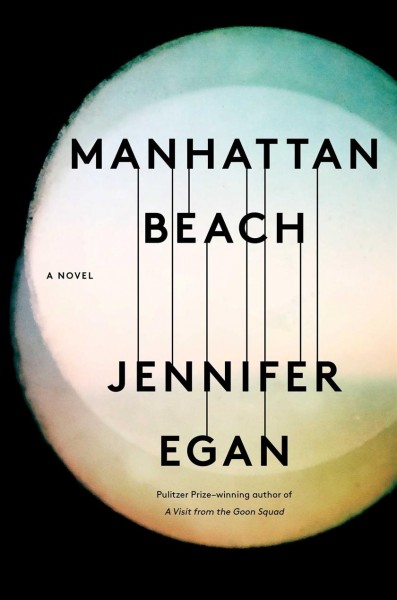

While the Coahoma County seat may not be a booming metropolis, the camera-wielding Mayfield frequently found herself in the right place at the right time, during culturally significant events and times over the past 30 years. Her casual stream-of-consciousness photo journal lets the reader in on the energy, with the perspective only a local could provide. The plot of Jennifer Egan’s latest novel

The plot of Jennifer Egan’s latest novel  In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book of essays

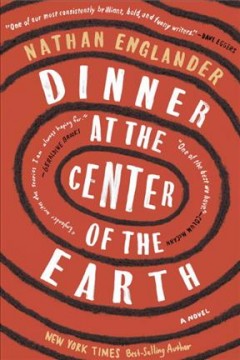

In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book of essays  The characters are built slowly, as the chapters flit between events in Germany, France, Italy, and Israel in 2002 and 2014. In the beginning, we don’t know the identity of Prisoner Z, or about the crime he committed to land him in prison.

The characters are built slowly, as the chapters flit between events in Germany, France, Italy, and Israel in 2002 and 2014. In the beginning, we don’t know the identity of Prisoner Z, or about the crime he committed to land him in prison.

I get emotional about the cover of my book. The musician–Arthneice Jones–is one of the most talented and articulate bluesmen I have known. A harmonica master and singer/songwriter, Arthneice was leader of The Stone Gas Band–a talented and popular bunch who played all over north Mississippi and Memphis before his untimely death. A musician who worked in concrete, Arthneice intrigued, charmed, and connected intimately with Sunflower acoustic audiences each summer with sidewalk philosophy mixed with music.

I get emotional about the cover of my book. The musician–Arthneice Jones–is one of the most talented and articulate bluesmen I have known. A harmonica master and singer/songwriter, Arthneice was leader of The Stone Gas Band–a talented and popular bunch who played all over north Mississippi and Memphis before his untimely death. A musician who worked in concrete, Arthneice intrigued, charmed, and connected intimately with Sunflower acoustic audiences each summer with sidewalk philosophy mixed with music. All the familiar denizens of the fictional town of Jericho, Mississippi, (faintly like the Oxford we all know, perhaps stripped to its roots) are there–if not in person, then in memory.

All the familiar denizens of the fictional town of Jericho, Mississippi, (faintly like the Oxford we all know, perhaps stripped to its roots) are there–if not in person, then in memory. An artist at heart, Spencer set out in 2003 on a quest to capture a post-9/11 America–to grasp a glimpse of a country of contrasts, fears, and hopes. The resulting book, he says, is “not a documentary or dogmatic statement, but rather an expression of the perception of the ideal.” The images are rendered in what he calls a “stream-of-consciousness perspective,” not “perfect pictures.”

An artist at heart, Spencer set out in 2003 on a quest to capture a post-9/11 America–to grasp a glimpse of a country of contrasts, fears, and hopes. The resulting book, he says, is “not a documentary or dogmatic statement, but rather an expression of the perception of the ideal.” The images are rendered in what he calls a “stream-of-consciousness perspective,” not “perfect pictures.”