Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (May 6)

Most of us, Suzanne Stabile says, “have no idea” that other people don’t see things the way we do.

Not only that, but they don’t process their experiences in the same way, either. And to make things even more interesting, it turns out that some of us rely mostly on our feelings, while others are thinkers; and still others are definitely “doers.”

The implications of these truths for relationships can be devastating or magnificent–or a lot of points in between.

Fortunately, Stabile can help us figure it all out. As a highly sought-after Enneagram master teacher, she knows how to help the rest of us bridge the gaps and come together.

In fact, when it comes to coming together, she wrote the book. The Path Between Us: An Enneagram Journey to Healthy Relationships not only describes the nine personality types of this ancient approach to behavior evaluation, but reveals how each relates to the others, fostering more mature and compassionate relationships at every level.

In fact, when it comes to coming together, she wrote the book. The Path Between Us: An Enneagram Journey to Healthy Relationships not only describes the nine personality types of this ancient approach to behavior evaluation, but reveals how each relates to the others, fostering more mature and compassionate relationships at every level.

Stabile is also the co-author of the bestseller The Road Back to You and, as an internationally recognized Enneagram master, she has spoken at more the 500 workshops at churches, colleges, and conferences around the nation.

She and her husband, the Rev. Joseph Stabile, are the founders of the Life in the Trinity Ministry in Dallas, Texas, a nonprofit, nondenominational ministry focusing on spiritual growth for adults.

What is the Enneagram, and how did you become interested in it?

The Enneagram is essentially nine ways of seeing. It is an ancient spiritual wisdom that teaches us that there are nine different ways of seeing and nine ways of experiencing the world. Additionally, there are nine ways of answering some of life’s basic questions like: “Who am I?” and “Why do I do the things I do?”

The Enneagram has an unknown origin, but has been used in all faith beliefs in one way or another for at least several hundred years and at most several thousand. The Enneagram is unique in what it offers us as we make our way from who we are to who we hope to be.

I read a book by Richard Rohr and my husband, a former Roman Catholic priest, and I started seeing Father Rohr on a regular basis and learning from his wisdom. Father Rohr was very encouraging about my interest in the Enneagram and he suggested I study without talking about the Enneagram for four or five years. I don’t think he would suggest that to everyone. That was specific to me because he knew I wanted to teach it.

Suzanne Stabile

I spent the time observing others, taking notes about how people were different from me, how they were different from each other, and only listening when others talked about the Enneagram. Without explaining it to me, Father Richard’s advice paved the way for me to gain a deeper understanding of the many facets of Enneagram wisdom.

As a result of my willingness to follow his instruction, when I began teaching, I had more than a passing knowledge of the numbers. I had embraced the depth and seemingly unending possibilities of how this ancient understanding could enhance our ability to be more compassionate with others and with ourselves. The practice of acceptance and the kindness that followed has served me well in every aspect of my life both personally and professionally.

Explain the spiritual component of the Enneagram.

My husband, Joe, and I led an institute for spiritual formation for a long time. It was a two-year program and one of the things we learned early on was that most people share in common the firs two stumbling blocks in a serious spiritual journey towards transformation. The first thing they run into is all the things they don’t like about themselves. That’s followed by the concerns and wounding they bring from family of origin. The wisdom of the Enneagram addresses both effectively.

We are each, by Enneagram number, well suited for some spiritual practices, but not for others. There is great frustration in trying to engage in a spiritual practice that isn’t suited to your number. It seems essential for those who want to know God, that they know themselves.

In your book, you explain the nine personality types: perfectionist, helper, performer, individualist, investigator, loyalist, enthusiast, challenger, and peacemaker. Why is it so important that we understand not only our own Enneagram type, but those with whom we have the closest relationships?

We all live with the idea that we are seeing the same thing and having the same experiences as those around us. We are not. Perhaps, that assumption is the greatest stumbling block for relationships. Learning how others see and process information is a game changer.

I’ve earned in recovery group settings that every expectation is resentment waiting to happen. Without an understanding of our differences, expectations are very likely. Resentment follows, and both discontentment and fragmentation are unavoidable.

The reason I teach the Enneagram is to increase compassion and civility in the world. If your only understanding is about your own number, then it limits rather than adds to our need for a more forgiving and compassionate world view. My teaching is taking a direction toward asking the question “what would be best for the common good?” We have individuated ourselves to such a degree that we’ve lost sight of the necessity for belonging to a great community, and for finding meaning in our lives by contributing to the larger community.

How is the Enneagram different from other personality tests?

In terms of other personality-typing systems, I think they’re all good and each has its place. As a spiritual wisdom tool, the Enneagram names us (according to our strengths, and at the same time provides us with information and opportunity to do something about what we’ve learned.

I have not found the online Enneagram tests to be accurate because they lack the ability to measure motive, the key factor in discerning one’s Enneagram number. That is one of the reasons I wrote the book. The Enneagram has been an oral tradition for centuries. Anyone who has the opportunity to hear the Enneagram taught orally by a qualified Enneagram master teacher will greatly benefit from that experience. The narrative approach has a lot of value because the Enneagram is deceptively simple, and nuance is very important. That nuance is best represented in stories.

What do you say to people who see Enneagram principles or conclusions in a skeptical light, or who may even have a fear that it could be dangerous in some way?

The world needs more acceptance and open-mindedness, and less suspicion and intolerance. Imagine the wars, fights, and pain that can be avoided by asking questions from a place of love and tolerance, rather than casting predetermined judgments from a place of fear and suspicion.

I am often asked, “what’s dangerous about the Enneagram?” I’ve given the question a lot of thought. As I know and understand this ancient wisdom, the only dangerous thing about the Enneagram is if it taken to be more than it is. It is literally just one spiritual wisdom tool. There are many others and they all have their own value. The Enneagram is just one, but it’s pretty great!

What if you read the book and feel like you cannot figure out where you fit among the Enneagram “numbers”?

The Path Between Us is not designed to introduce readers to the nine Enneagram types, instead it is based on the idea that the reader is already aware of his or her own Enneagram type. We can’t recommend highly enough the value of starting with my Enneagram primer, The Road Back to You that I co-authored with Ian Morgan Cron.

Another possibility would be to listen to my “Know Your Number” recordings, or even better, attending a Know Your Number workshop in person. There will be a Know Your Number workshop in Jackson in January 2019, taught by my daughter Joey. I will be there later in the month for an advanced Enneagram workshop.

Why do you believe that more and more people are becoming interested in studying the Enneagram today?

The generations that have followed the baby boomers seem to be more interested in understanding themselves individually rather than collectively. It seems that they have more space for difference and more tolerance for “the other.” The Enneagram, by its very nature, fits within that context as a way of thinking.

At this time in our culture, people don’t seem to be turning only to the church to try to understand life. It doesn’t take long on a journey towards self-knowledge to develop an interest in tools like the Enneagram that have a way of explaining how we’re like other people and how we are different.

From my perspective as a Christian, I would add that the Enneagram helps us in knowing ourselves, so that we might know God and then better understand ourselves in relation to God.

What is your hope for people who read your new book?

I actually believe we are in a relationship crisis. We are becoming more polarized as we try to navigate the episodic meaning that defines our lives both individually and collectively. And, we seem to know ourselves by what we are against instead of by what we are for. We’re more tribal than at any other time in my lifetime and as a 67-year-old that is astonishing to me.

When people are taught the Enneagram by someone who knows it well, it can change how they see the world and how they interact with those who see it differently. Once people are exposed to this ancient wisdom, they begin to respond to difference with curiosity instead of judgment. They respond to misunderstanding with compassion instead of rejection, and diversity becomes a gift instead of a stumbling block.

Suzanne Stabile will be at Lemuria on Tuesday, May 8, at 5:00 to sign and read from The Path Between Us: An Enneagram Journey to Healthy Relationships.

But mostly, it’s a tribute to his mother, 81-year-old Margaret Bragg, whose skills in the kitchen, he says, are still unmatched. This is a woman who never—not once—used a cookbook, a written recipe, a measuring cup or even a set of measuring spoons to put a meal on the table. Her skills came from oral recipes and techniques that go back generations—some even to pre-Civil War days.

But mostly, it’s a tribute to his mother, 81-year-old Margaret Bragg, whose skills in the kitchen, he says, are still unmatched. This is a woman who never—not once—used a cookbook, a written recipe, a measuring cup or even a set of measuring spoons to put a meal on the table. Her skills came from oral recipes and techniques that go back generations—some even to pre-Civil War days.

In

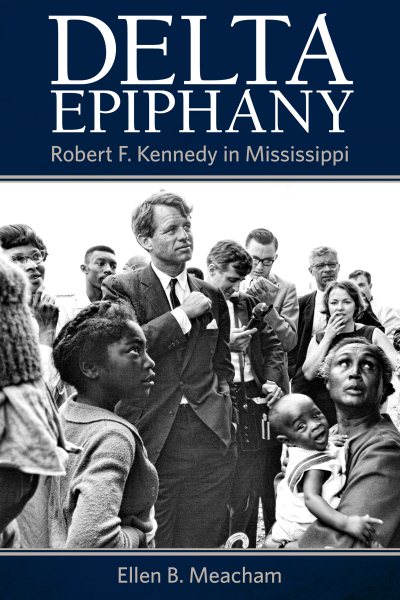

In  But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor.

But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor.

I was interested in the fact that she left Mississippi shortly after Jefferson Davis died and moved to New York City to become a newspaper writer when she was over 60 years old. I found out that she had lived in London for some time, alone. As she grew older, she stayed engaged with the world around her and her opinions continued to evolve. At a time in life when most people start slowing down, she was digging her heels in, thinking mostly about her work, writing.

I was interested in the fact that she left Mississippi shortly after Jefferson Davis died and moved to New York City to become a newspaper writer when she was over 60 years old. I found out that she had lived in London for some time, alone. As she grew older, she stayed engaged with the world around her and her opinions continued to evolve. At a time in life when most people start slowing down, she was digging her heels in, thinking mostly about her work, writing.

Set in Kardos’s native New Jersey, the novel starts with close-up magician Natalie Webb, on the verge of being washed up at 27, almost blinding a smarmy lawyer at a corporate holiday show by throwing a playing card at his eye. It’s a compelling and darkly funny opening, one that sets the tone for the rest of what’s to come: a book that expertly walks the line between breeziness and brutality.

Set in Kardos’s native New Jersey, the novel starts with close-up magician Natalie Webb, on the verge of being washed up at 27, almost blinding a smarmy lawyer at a corporate holiday show by throwing a playing card at his eye. It’s a compelling and darkly funny opening, one that sets the tone for the rest of what’s to come: a book that expertly walks the line between breeziness and brutality. His newest book,

His newest book,

Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale.

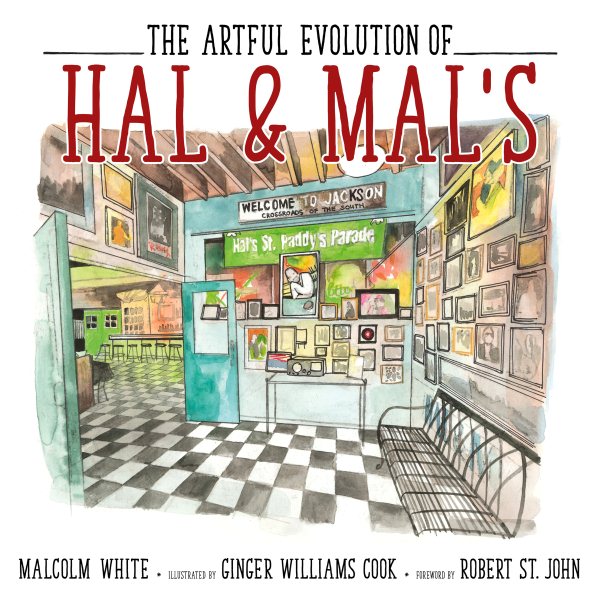

Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale. Hal & Mal’s is not one story, but many, and the book sheds a warm and witty light on the background and influences that fed into this cultural outpost in Jackson’s downtown. Of all those vines, family clings the strongest with tendrils in every story of the boys who grew up in Perkinston and Booneville, lost their mother young, and held the love of father, stepmother, brother, grandparents, relatives and friends close.

Hal & Mal’s is not one story, but many, and the book sheds a warm and witty light on the background and influences that fed into this cultural outpost in Jackson’s downtown. Of all those vines, family clings the strongest with tendrils in every story of the boys who grew up in Perkinston and Booneville, lost their mother young, and held the love of father, stepmother, brother, grandparents, relatives and friends close.