Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (August 12)

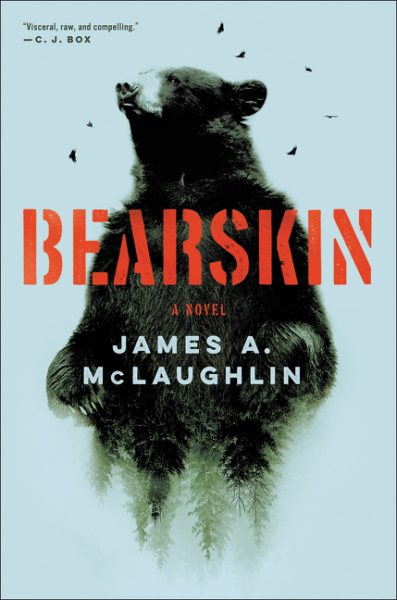

James McLaughlin admits he’s been surprised with the reception his debut novel Bearskin has received, but the topic of the book–which he said his publishers told him was difficult to categorize–is a very familiar to the Utah outdoorsman.

Growing up in rural Virginia as both an avid reader and a lover of the outdoors, McLaughlin had already decided, as a high school student, that he “was going to be an ‘outdoor writer,’ whatever that meant.” As a child, he spent much of his time hunting, fishing, and exploring the woods around his family’s farm. Reading material naturally ran to Tarzan, Jack London, James Oliver Curwood, and Hemingway’s “hook and bullet stuff”–not to mention books on backpacking, camping, and how to survive in the woods–along with a subscription to Gray’s Sporting Journal.

His circuitous educational route set him on the path to the notable success of Bearskin, a rough and tumble thriller that contrasts the brutality of human capability with the primitive beauty of nature’s untouched wilds. Set in a remote private nature reserve in the heart of Appalachia, the story plays out with a precarious mix that includes a hostile drug ring, a love interest, a regretful past, hallucinatory episodes–and mutilated bears whose body parts have been stolen for drug-dealing profiteers. In brief, it runs the gamut from wild action to deep contemplation and plenty of raw secrets.

His circuitous educational route set him on the path to the notable success of Bearskin, a rough and tumble thriller that contrasts the brutality of human capability with the primitive beauty of nature’s untouched wilds. Set in a remote private nature reserve in the heart of Appalachia, the story plays out with a precarious mix that includes a hostile drug ring, a love interest, a regretful past, hallucinatory episodes–and mutilated bears whose body parts have been stolen for drug-dealing profiteers. In brief, it runs the gamut from wild action to deep contemplation and plenty of raw secrets.

It was after McLaughlin earned a law degree from the University of Virginia that he would soon realize he “was not built for the office,” and returned to UV to get his MFA–and then it was back to reality.

“Pretty quickly, I figured out that in order to eat while writing I would have to practice law part-time,” he said.

He said he “eventually specialized in land conservation law, and after my wife and I moved to Utah in the early aughts, I partnered up with a close friend when he started a conservation consulting business back in Virginia. I still work with the business several days a week–telecommuting, traveling east three or four times a year–and my partner has been generous in allowing me time to write.”

That “time” has also resulted in fiction and essays that have appeared in the Missouri Review, the Portland Review, River Teeth, and elsewhere. Today, he lives in a the Wasatch Range east of Salt Lake City, Utah.

McLaughlin will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival August 18 as a participant in the “The Rough South” Southern fiction panel panel at 12:00 p.m. at the Galloway Foundery. He will be at the book signing tent at 1:45 p.m.

Bearskin is your debut novel, and press attention has been substantial, including coverage in the Washington Post, USA Today, Entertainment Weekly, Goodreads, and the New York Times, who named you one of the “Summer’s Four Writers to Watch”–quite a feat for a first novel! Have you been surprised by the media and fan attention for this book?

Completely surprised. I’ve been fortunate, and I know the Ecco and HarperCollins folks have done a lot of work putting the book in the right hands. From the beginning, they’ve said while Bearskin was a hard book to categorize–it doesn’t fit perfectly into any particular pigeonhole–they only needed to get people to read it, and it would do OK.

The novel tracks the story of main character Rice Moore, whose past is filled with enough problems of its own (he’s fleeing ties with a Mexican drug cartel) before he moves to a secluded forest reserve in Virginia hoping to escape terrible secrets–only to find that he feels compelled to go after game poachers killing native bears for drug dealers who want to profit from the sale of their parts. what influenced the idea for this book, including its setting deep in the Appalachian wilderness?

The story idea and the setting are tied up together: they first came to me back in the ’90s when I heard about people finding mutilated bear carcasses in the mountains near where I grew up in western Virginia. I found out the bears were being poached to supply a global black market, and organized crime was reportedly involved. It seemed a natural backdrop for a story. I knew the setting well because I’d grown up wandering around in those mountains.

And Rice Moore’s background…he was brand new to me when I decided to rewrite the book after setting it aside for 10 years. My first image of Rice was as a tough, capable person who is unaccountably spooked by the shadow of a vulture. Why is he so jumpy? His history of smuggling for a cartel grew out of my efforts to answer that question.

From the first scene of the story on page 1, the plot takes on a violent tone, and remains edgy throughout. Were there other thriller authors whose writing inspired you to pursue this genre?

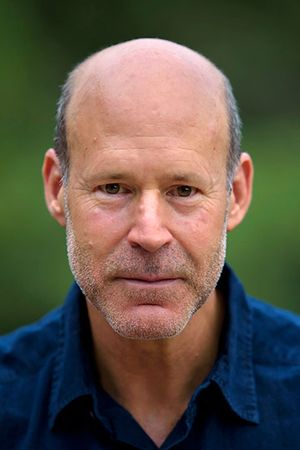

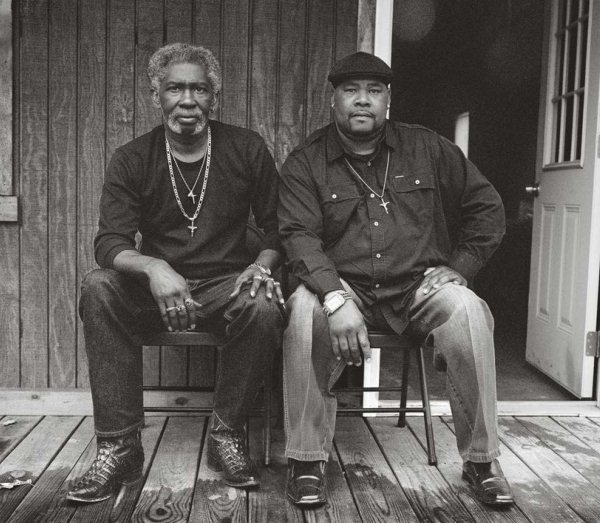

James McLaughlin

I always preferred books with a lot of action, and I didn’t mind violent action, and I have to admit I never outgrew that preference. For years, I mostly read writers like Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Rick Bass, Peter Matthiessen, Ed Abbey, James Dickey, and Cormac McCarthy, who came out with No Country for Old Men a couple of years before I decided to reimagine Bearskin. You find violence in some of those guys’ work, but they’re not genre.

Then in the early-mid-aughts I started reading and enjoying and admiring more crime, mystery, and thriller authors like John Lawton, Lee Child, Tana French, Don Winslow. I’m sure all of those influences affected how I approached the myriad decisions made during the rewriting process. Rice Moore kept insisting on violent thriller elements, and I kept writing them in.

What are we to make of Rice’s hallucinations and frequent feelings of dislocation, often mentioned along with his severe sleep deprivation?

That stuff is important to Rice’s psychology, and yes, one aspect is the “fugues” he suffers from time to time–his first occurs in the violent prologue scene–where he temporarily loses his sense of self and becomes disoriented.

The fugues are a manifestation of trauma, I think. He’s traumatized by what happened to him, what he has done to others, and by what he fears is coming for him. He’s repressing his memories, his past, his violent nature, but at the same time he’s wide open, unguarded against his current circumstances.

When the main narrative begins, for months he has been living alone and in an emotionally vulnerable state in a remote and ancient forest. The place has a serious mojo, whether it’s purely biological or possibly supernatural–a local tells him the mountain is haunted. Rice has come to feel relatively safe there, and without quite realizing it, he has entered into an intense relationship with the forest, the mountain, the rich ecosystem he has been immersed in.

After he starts finding bear carcasses, for various reasons he becomes obsessed with catching poachers and pushes himself way past his own limits–he always has had a tendency to over-do things. He stops sleeping, he doesn’t return to the lodge, he fasts. He’s already vulnerable, so these stressors mess with his head. Gradually at first, then more insistently, his confidence in the distinction between real and imagined or dreamed experience erodes. He may be experiencing some reality that’s otherwise inaccessible, or he may just be hallucinating.

I wanted to explore what happens when a person opens up to the world in a truly extreme way and experiences a wild, ancient place without the usual filters. For some folks, it’s their favorite part of the novel. Others don’t know what to make of it.

Why did it take more than two decades to write this book, as I’ve read? (Even though the book actually reveals dual plots, the way you’ve organized it explains the whole story very clearly!)

It’s fun to say that it took 20 years, and that is the span of time from when I started to when it was published–actually it was almost 24 years–but really, I wrote it in two stages: first I spent several years writing a first novel about a guy who encounters bear poachers on his family’s property. That one, also titled Bearskin, wasn’t published.

Then, years later I started over, using the same setting and the bear poaching premise, but with new characters. I wrote the first few chapters over several months, and that part was published as a novella in the Missouri Review, but when I finally sat down to extend it into a new novel, it took four years to finish a draft and then another 18 months of revising before my agent took me on. More revision followed, of course.

Your writing style is very “efficient”–not a lot of wasted words. How would you describe it, and how did it develop?

Thank you. It’s funny because I enjoy and admire a number of writers who are known for their flamboyant writing, but it does seem I generally have a low tolerance for wordiness in my own work. I revise a lot, and it seems as I’m revising I’m usually cutting instead of adding. That might be one reason it take me so long to write anything.

I haven’t thought about how I’d describe it. Maybe I’m trying to convey what I’m after without forcing the reader to wade through too much self-indulgent prose?

I understand you are already working on a prequel AND a sequel to this book. Please tell me about that!

It may be overstating it to call it a prequel, but my next novel is one I’ve worked on intermittently for years, and right now it looks like Rice and his girlfriend Apryl will show up near the end when the setting moves to southern Arizona.

More to the point, I’m working on notes and plans for a third book that will more directly follow Bearskin. Rice Moore and the other characters in Bearskin are compelling, and I’m definitely not yet finished with them.

Bearskin is Lemuria’s August 2018 selection for our First Editions Club for Fiction.

Too often it takes years, but right can triumph over wrong. In

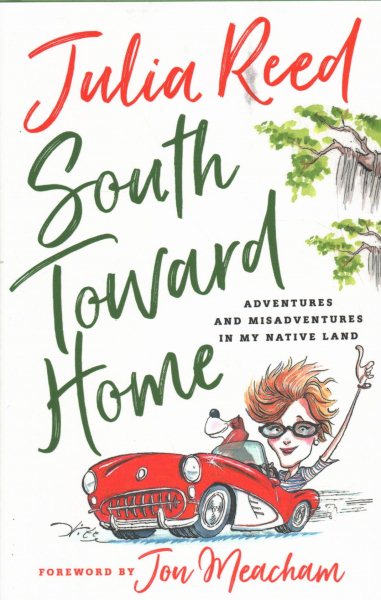

Too often it takes years, but right can triumph over wrong. In  Mississippi’s Julia Reed, a columnist and author of six previous books, has blessed her fans with yet another salute to the South, this time with

Mississippi’s Julia Reed, a columnist and author of six previous books, has blessed her fans with yet another salute to the South, this time with

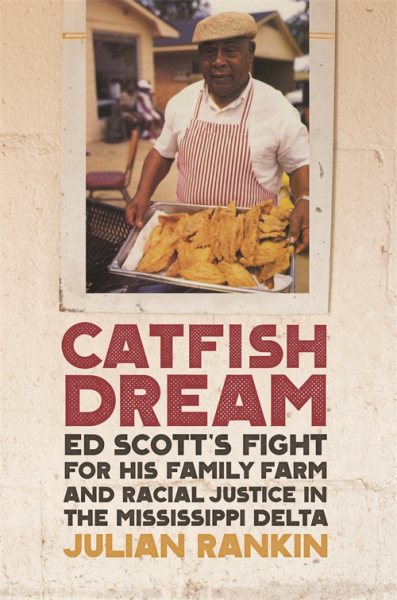

Saturday, August 18, will be full of panels, many often occurring simultaneously. Nestled between discussions that focus on authors or themes or genre books is a panel that features a book publisher. Often neglected at this sort of event, the Mississippi Book Festival has chosen each year to highlight a different press that is bringing great books to the world. Billed as,“an inside look at the ups and downs of publishing and the relationship between a national literary publisher and two of its award-winning authors,” this year’s publishers panel will host

Saturday, August 18, will be full of panels, many often occurring simultaneously. Nestled between discussions that focus on authors or themes or genre books is a panel that features a book publisher. Often neglected at this sort of event, the Mississippi Book Festival has chosen each year to highlight a different press that is bringing great books to the world. Billed as,“an inside look at the ups and downs of publishing and the relationship between a national literary publisher and two of its award-winning authors,” this year’s publishers panel will host

Gary Krist’s fascinating account of the history of Los Angeles during the first three decades of the 20th century puts a highly personal face on the mage-city’s early days through the almost unbelievable stories of three of its most interesting and important influencers in

Gary Krist’s fascinating account of the history of Los Angeles during the first three decades of the 20th century puts a highly personal face on the mage-city’s early days through the almost unbelievable stories of three of its most interesting and important influencers in

Underscored by the sudden death of Ball’s long-time partner, each poem in

Underscored by the sudden death of Ball’s long-time partner, each poem in  Following the debut release of

Following the debut release of

Clock Dance

Clock Dance In her new book,

In her new book,