Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (September 30)

National Book Award finalist Elliot Ackerman shows his grit as both a tested warrior and intrepid wordsmith with his new release Waiting for Eden, a fiercely moving novel about how the wounds of war linger beyond life itself.

National Book Award finalist Elliot Ackerman shows his grit as both a tested warrior and intrepid wordsmith with his new release Waiting for Eden, a fiercely moving novel about how the wounds of war linger beyond life itself.

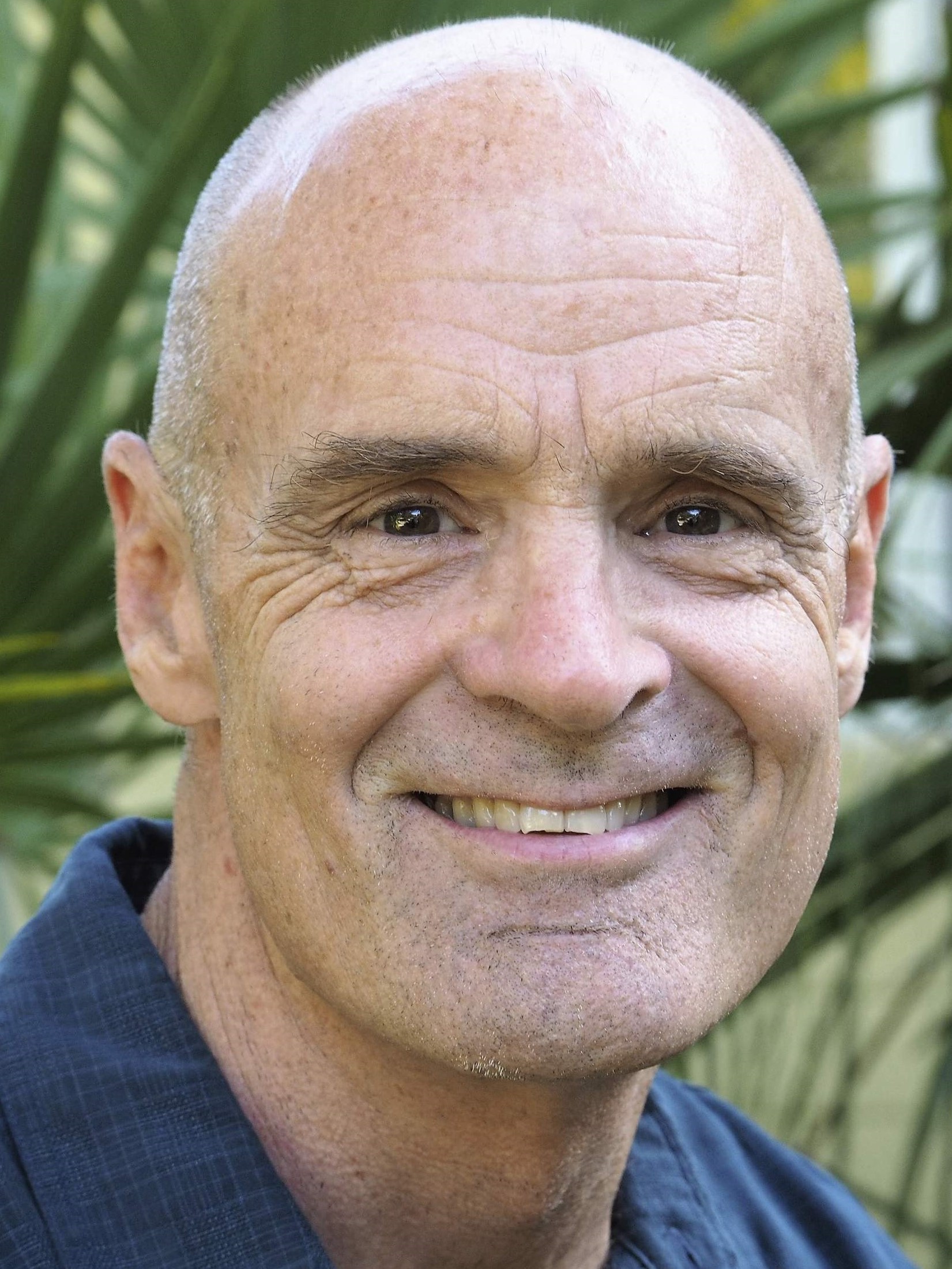

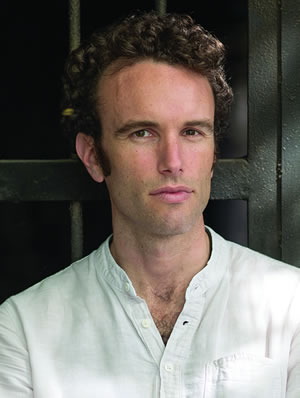

It was five tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan that earned the former U.S. Marine the Silver Star, Purple Heart, Bronze Star for Valor and the distinction of White House Fellow–and it would be his novel Dark at the Crossing that secured his finalist spot for the National Book Award in 2017. His also authored the acclaimed novel Green on Blue.

Other writings and articles by Ackerman have appeared in Esquire, The New Yorker, The Atlantic and The New York Times Magazine, as well as The Best American Short Stories and The Best American Travel Writing.

Ackerman divides his time between New York City and Washington, D.C.

Elliot Ackerman

How do you align your remarkable military career with your accomplishments as a writer?

People who don’t know me often say they’re surprised that I would have gone from the Marines into the arts. However, people who knew me growing up often say it surprised them that I went into the Marines instead of the arts. Those who aren’t familiar with the military often view it as a monolith. Nothing could be further from the truth. Some of the most talented writers, playwrights, and artists I know spent time in the service. That’s true today and it’s been true in the past.

The tone, the structure and the plot of Waiting for Eden are all striking in their uniqueness. The story itself is brutal, yet gentle–and obviously influenced by your own years in the military. How did you form the idea for this emotional and unexpected tale?

If you spend any time at war, you get acquainted with loss. That was a big part of my war experience. I learned about losing people that I loved when I was young; I was 24 when my first friend was killed in combat. Obviously, those who fight in a war aren’t the only ones who are acquainted with loss. A parent, a sibling, a friend– who among us isn’t touch by similar loss?

I wanted to tell a story about the wars, but also one that transcended the wars and dealt with issues that are universal, which is why so much of the book occurs at home. Grief was a theme that interested me. We often think of grief as a transitory state. We suffer a loss, then we grieve, and then through our grief we’re able to move on. But what if you can’t move on? At its core that’s what this novel is about.

Eden Malcom, the main character, is a victim of a tragic explosion during a deployment in Iraq. He is left with terrible injuries that leave him badly burned and clinging–for three long years–to life. His wife Mary spends those years by his side every day in a San Antonio burn center. His best friend, the book’s narrator, is actually dead but can see, hear, and understand Eden’s thoughts and feelings. This would probably be a good place to ask you to explain the title of the book.

The opening lines of the book are, “I want you to understand Mary and what she did. But I don’t know if you will. You’ve got to wonder if in the end you’d make the same choice, circumstances being similar, or even the same, God help you.”

When you meet Mary and the unnamed narrator at the beginning of the book, they have been waiting for three years for Eden to succumb to his wounds. They have no hope that he might recover; his injuries are too severe. Mary lives at the hospital, having sent her young daughter to live with her mother, and Eden’s best friend remains in a quasi-purgatory, hovering over the narrative as he tells us Eden’s story. So with Mary at the hospital and his best friend watching on the other side of life, these two have kept faith with Eden.

But what they are really doing is grieving, because grief is a type of faith; contained within it is the belief that eventually our spirits will heal. I’m not sure the healing always happens. When it doesn’t, we are left with something other than grief. We are left waiting. Hence the title of the novel.

Tell me about Eden’s phobia of–and ongoing battle with–cockroaches.

Like Eden, cockroaches are virtually indestructible. They’re one of the few species of animals that would survive a nuclear holocaust. They’re impervious to radiation and most diseases. Few creatures can withstand quite as much punishment as a cockroach. So Eden has this in common with them. But he also has a phobia of them, and this phobia predates his horrific injuries. It’s as though he knows what he is going to become, and it terrifies him, causing his phobia to act on a subconscious level. Here he is thinking of the cockroaches he imagines are lingering in the crevices of his hospital room, “He knew they’d crawl over him before he could even get a look and he did the only thing he could: he waited.”

In what ways did John Milton’s Paradise Lost influence this book–and the name of the main character?

The idea of original sin, which is present in Paradise Lost, certainly influenced this book. More than anything else, this is a book about a marriage and the sins that occur within a marriage and the way that they project out through our lives. The idea of an Eden, or paradise, goes hand-in-hand with the idea of original sin. Eden is the place before the sin, the place we are trying to get back to. This too is what they’re waiting for.

The devotion Mary shows for her husband is fierce and steadfast, and is one that would be difficult, if not impossible, for many spouses. What drives Mary’s strength and determined commitment to her suffering and slowly dying husband?

There’s a saying I’ve always like–it does come from my Marine days, and it was spoken about the Marines on Iwo Jima. You’ve probably heard it: “Uncommon valor was a common virtue.” You would be surprised what people are capable of when placed into extraordinary situations. Mary’s situation is most certainly extraordinary. The extent of her husband’s wounds, and the choice she is asked to make, none of this is everyday stuff. However, I don’t think that her devotion, which I would certainly characterize as fierce and steadfast, is quite as extraordinary as many of us might think. Mary rises to the occasion as so many of us are often called upon to do.

Through Waiting for Eden, what did you wish to tell readers about war?

I don’t consider Waiting for Eden to be a book about war; it is a book about grief and one that I hope will resonate for those of us who’ve ever struggled to let go of a person we’ve loved. What I prize about fiction is that it isn’t trying to tell us anything. When I wrote this book, I felt something as I put down this story on the page. If you, as the reader, feel any fraction of what I felt for these characters then the transfer of that emotion is the goal; it is what I hope you would take away from this book, as opposed to my telling you anything about a certain subject.

In the final pages of the book, Eden is pleading for the end of his life to finally come, and his wife makes a surprise decision that also affects his best friend, the narrator. Can you tell us (without spoiling the end) what they are all really waiting for?

I don’t want to spoil the end, so I’ll simply say that there is a common love that three of them share. Through that love they hope to be made whole, to return–at least in some small way–to their lives before the original sin.

Do you have your next book project already in the works yet?

My next book, Places and Names: On War, Revolution, and Returning will be out in May 2019. It is a piece of nonfiction which deals with my time in both Iraq and Afghanistan, expatriate life in Turkey, and my coverage of the Syrian Civil War. I am also finishing a novel set in Istanbul, where I used to live, and it is scheduled for release the year after that.

Elliot Ackerman will be at Lemuria on Monday, October 22, at 5:00 to sign and read from Waiting for Eden, which has been selected one of our November 2018 selections for Lemuria’s First Editions Club for Fiction.

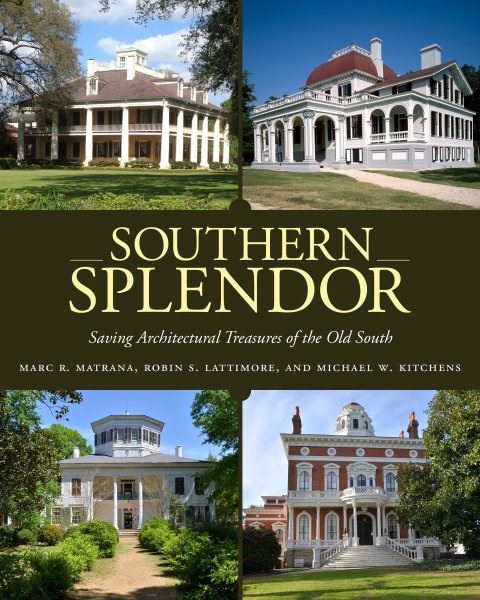

It took Marc R. Matrana, Robin S. Lattimore and Michael W. Kitchens–the authors of

It took Marc R. Matrana, Robin S. Lattimore and Michael W. Kitchens–the authors of

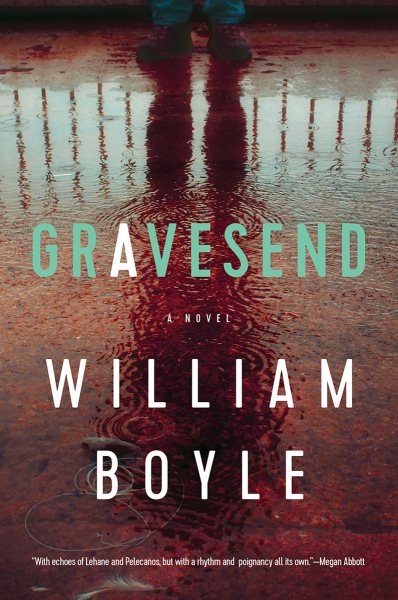

Gravesend is a glum, gritty, depressing place on the wrong side of the Brooklyn tracks—but it’s also an old, close-knit neighborhood with a small-town feel, where everyone knows everyone else and everyone else’s business.

Gravesend is a glum, gritty, depressing place on the wrong side of the Brooklyn tracks—but it’s also an old, close-knit neighborhood with a small-town feel, where everyone knows everyone else and everyone else’s business. Set in the fictional small town of New Canaan, Ohio, Markley’s moving debut novel conveys the angst of a region in decline–thanks to the realities of an economic recession, the tragedy of opioids, and the calamities of war in Afghanistan and Iraq–as witnessed by four former high school classmates. When the friends, all in their 20s, gather in their hometown one fateful summer night in 2013, the evening ends in a shocking culmination that no one expected.

Set in the fictional small town of New Canaan, Ohio, Markley’s moving debut novel conveys the angst of a region in decline–thanks to the realities of an economic recession, the tragedy of opioids, and the calamities of war in Afghanistan and Iraq–as witnessed by four former high school classmates. When the friends, all in their 20s, gather in their hometown one fateful summer night in 2013, the evening ends in a shocking culmination that no one expected.

Although

Although

And that’s where bestselling author Lisa Patton, a Memphis native, current Nashville resident and graduate of the University of Alabama, chose to set her newest novel,

And that’s where bestselling author Lisa Patton, a Memphis native, current Nashville resident and graduate of the University of Alabama, chose to set her newest novel,

As a reporter for The Commercial Appeal, Perrusquia caught wind of a tantalizing story: that one of Memphis’ most well-known and respected Beale Street residents who had rubbed shoulders with the highest leaders of the movement was for nearly 20 years an FBI informant.

As a reporter for The Commercial Appeal, Perrusquia caught wind of a tantalizing story: that one of Memphis’ most well-known and respected Beale Street residents who had rubbed shoulders with the highest leaders of the movement was for nearly 20 years an FBI informant. The chance meeting of British journalist Helen Gibbs and French-American financier Christopher Delavaux on a Mexican beach leads to a relationship and a marriage that would become threatened by ambition and time apart–and ultimately, a difficult choice that must be made for

The chance meeting of British journalist Helen Gibbs and French-American financier Christopher Delavaux on a Mexican beach leads to a relationship and a marriage that would become threatened by ambition and time apart–and ultimately, a difficult choice that must be made for

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.