Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 11)

A decade after his successes with Peace Live a River and So Brave, Young, and Handsome, New York Times bestselling author Leif Enger offers his third novel, Virgil Wander with a twist.

The award-winning novelist’s portrayal of a good-natured man whose hopes and dreams are literally forgotten when his memory is wiped out after “his Pontiac flies off a bridge into the icy depths of Lake Superior” is at once contemplative and relatable.

The award-winning novelist’s portrayal of a good-natured man whose hopes and dreams are literally forgotten when his memory is wiped out after “his Pontiac flies off a bridge into the icy depths of Lake Superior” is at once contemplative and relatable.

Emerging alive but with language and memory deficits, main character Virgil Wander has no choice but to build a new life amid the trappings of his former one. Set in fictitious Greenstone, Minnesota, his town is struggling to revive itself after years of deterioration. Supporting characters rally to the cause as they deal with their own struggles.

The author’s hometown of Osakis, Minnesota (population 1,700), proved to be the perfect springboard for a young person with hopes of someday writing fiction, and Enger’s time came after working as a reporter and producer for Minnesota’s Public Radio.

Enger’s debut novel Peace Like a River won the Independent Publisher Book Award and was a Los Angeles Times and Time Magazine pick as one of their Best Books of the Year; and So Brave, Young, and Handsome was a national bestseller.

He and his family live in Minnesota.

The front flap of your book describes Virgil Wander as a “journey into the heart and heartache of an ‘often overlooked’ upper Midwest.” Explain what that means.

I’m not sure overlooked is the right word–“oversimplified” might be closer to the truth. Though often credited with timeless moral sensibilities, moderation, and a crackerjack work ethic, Midwesterners are as complicated and devious as anyone else.

That said, I suspect neither of the above–being overlooked or oversimplified–is much on our minds. Everyone wants respect, but there’s an enormous freedom in being off the radar. There’s still high value on self-sufficiency and almost everyone would rather give help than receive it. Of course, there’s plenty to complain about in places like Greenstone–high unemployment, clouds of mosquitoes, the tiresome March climate–but I’ve never heard anyone gripe about being ignored by Anderson Cooper.

I read about your hometown of Osakis and see that it has a population of 1,700 people. How did this influence your interest in writing?

Leif Enger

Growing up in Osakis was advantage in lots of ways. I had teachers throughout grade and high school who made me feel capable and encouraged my writing–not because I had some precocious gift, but because I liked words, especially funny ones, and because I wasn’t intimidated by essay questions. I think they just appreciated that I did the assignments, and they themselves didn’t think of writing as something exotic but as an everyday skill that could be useful in anyone’s life. They also knew that for me, it was never going to be math!

And there was a sense of relaxed-ness in that time and place about academics, sports, social events, and extra-curriculars, that allowed a kid–at least a lucky kid, with careful loving parents–to grow up slowly, without constant supervision. We went outside a lot because it was interesting out there. The news was not yet swamped with abductions and school shootings. We bumped into things but were mostly unhurt, and while we all hoped vaguely for eventual success, I don’t remember any outrageous expectations or pressure to produce. Of course, it’s also possible that with greater pressure I’d have produced more than three novels in 18 years. I guess we’ll never know.

Briefly, tell us about Virgil Wander. What inspired this hapless yet hopeful character and his story?

A certain kind of outsized American ambition is so celebrated, and its heroes so ubiquitous–the bold deal-making businessman with his strong handshake and empty sockets, the congressman who encountered Ayn Rand and never got over it, the 70-year-old with sculpted abs and restored sex drive–that it’s basically a cartoon. Whoever draws Tony Robbins is hilarious. I have no problem with this distortion until it’s held up as ideal, which it always is. Most of us are fairly pleased to get the kids through school, pay off the house, and act decently to our wives or husbands–maybe some days we even get the 10,000 steps that reassure us we’re doing all right.

So, writing Virgil was a matter of looking at my own easygoing ambitions and translating them into a context I’ve always sort of envied, namely running a slump-shouldered movie house in a stark little town on the edge of the inland sea. That’s a reality I can understand, and its modesty also allows for an element of magic that probably wouldn’t work otherwise. Magic only works when it’s badly needed, and I’ve never written a character who needed it more than Virgil.

The plot you weave is filled with colorful characters with whom Virgil connects as he struggles to literally “find himself” after his near-death experience of plunging into Lake Superior. Each of these characters supply subplots of hurts and hopes all their own. Together, they hope to reclaim and revive their “hard luck” town. In what ways does this narrative reflect stories of the “forgotten Midwest”?

No matter where you are, difficult times present a temptation toward nostalgia–to reclaim a remembered golden age by trying to re-establish formulas for success that worked once years ago. But shifts in demographics and technology doom the nostalgic impulse, and what’s happening in Greenstone is a result of that tension playing itself out over the decades. Jerry Fandeen, the former blasting engineer, deals with it by reaching back into the past, which can only end in despair; meanwhile his wife, Ann, has an entirely different response and spins out any number of creative and sometimes ludicrous ideas for an energized and dynamic future.

Most of the characters in the book are struggling to release their history and find a way forward. So are may of us in real life, and not just in the Midwest, anywhere livelihoods have been derailed by supply-chain disruptions or accidents of policy or just plain apathy. What seems hopeful to me is how hard people are willing to work for even small improvement in their lives, and their neighbors’ lives. At one point, Virgil remarks: “We all dream of finding, but what’s wrong with looking?” That’s a modest sort of optimism, which to me is the best kind, because it feels sustainable.

What has your writing success with your previous books (Peace Like a River and So Brave, Young, and Handsome), as well as your collaborations with your brother Lin Enger, taught you about writing–and about life?

Any regular writing discipline teaches you first to pay attention–to physical details, the colors and textures around you, the bird calls, squealing fan belts, burning muscles on an uphill walk, what E.B. White called “the smell of manure and the glory of everything.” That would be enough of a benefit, but then language itself has a way of tantalizing you along with new and ever more evocative words, rhythms, new ways of clarifying things said a thousand times before, as anything worth saying has been.

When Lin and I were writing crime novels together, he said the object of writing was clarity, “the opposite of showing off,” and that the goal of a novel was for the reader to forget he was reading.

I’m not wise enough to know how that relates to life itself, but I think it makes for a good book.

Tell me about the appearance of Minnesota native Bob Dylan in this story–are you a fan?

I came to Dylan pretty late, and I am not by any stretch a Dylanologist or obsessive fan, but I love how his songs seem to come up from the ground, how you know them by their mood, they have a kind of weather about them, a compact but powerful storm system. Listening to Dylan always makes me feel sad, but somehow prepared, ready to bear up under whatever is coming; I also love how he keeps writing good songs after so many years, an inherently hopeful thing to do. Because of these things, and because Greenstone would be practically in his backyard, I tried to conjure him in a way that would seem real and useful, and maybe a little bit funny.

I assume you love baseball, as a player is included in this book and was in previous works of yours. Is that a passion for you?

It’s the prettiest game, to me. Dad was a terrific pitcher, as was his brother Clarence, and their dad as well, Buck Enger. Clarence, in fact, was the model for Alec Sandstrom–according to Dad, Clarence was the one with the real velocity, but little control. In fact, Dad said, when Clarence pitched, it was not uncommon for opposing players to refuse to bat. They’d bench themselves first. Batting helmets didn’t exist in those days.

Do you have other writing projects out there on the horizon that you can tell us about?

I have a couple of novels in mind and am making notes for them, but would rather not say anything more–I’m a little superstitious about that.

Leif Enger will be at the Eudora Welty House on Thursday, November 15, at 5:00 to sign and read from Virgil Wander. Virgil Wander is Lemuria’s December 2018 selection for its First Editions Club for Fiction.

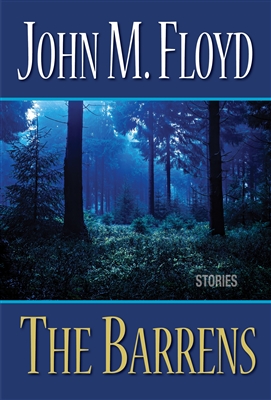

Well, the season is upon us: hundreds of hungry children dressing up like princesses and superheroes, anticipating candy by the truckload. But my treat came early in the form of John M. Floyd’s seventh exciting collection of mystery short stories.

Well, the season is upon us: hundreds of hungry children dressing up like princesses and superheroes, anticipating candy by the truckload. But my treat came early in the form of John M. Floyd’s seventh exciting collection of mystery short stories.  Cobb’s new book,

Cobb’s new book,

In

In  But in

But in  How the couple has gotten to this point is the result of two lifetimes of struggles and triumphs as documented in their memoir,

How the couple has gotten to this point is the result of two lifetimes of struggles and triumphs as documented in their memoir,

While this “modern day reinterpretation” of the classic book has retained many favorite recipes from the original, it is filled with popular choices from recent editions of Southern Living magazine, and many of Heiskell’s own favorites. Menus include appetizers, main dishes, drinks, and desserts for a Bridal Tea, Garden Club Luncheon, Summer Nights, Cocktails and Canapés, Tailgate, Picnic on the Lawn, Fall Dinner, and 24 more occasions.

While this “modern day reinterpretation” of the classic book has retained many favorite recipes from the original, it is filled with popular choices from recent editions of Southern Living magazine, and many of Heiskell’s own favorites. Menus include appetizers, main dishes, drinks, and desserts for a Bridal Tea, Garden Club Luncheon, Summer Nights, Cocktails and Canapés, Tailgate, Picnic on the Lawn, Fall Dinner, and 24 more occasions.

It’s a fascinating voyage into the Golden Age of Piracy that not only proves true some of the stereotypes of legend, book and film, but also debunks others and shockingly reveals the depth of early America’s connection to the outlaw seafarers.

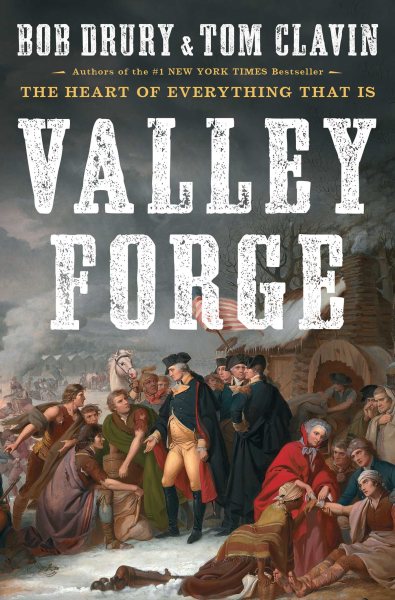

It’s a fascinating voyage into the Golden Age of Piracy that not only proves true some of the stereotypes of legend, book and film, but also debunks others and shockingly reveals the depth of early America’s connection to the outlaw seafarers. Though lesser known than other heroic military campaigns throughout America’s history, the struggle that played out along the frozen shores of the Chosin Reservoir in the snowy mountains of North Korea in 1950 tested the mettle of the First Marine Division beyond reason.

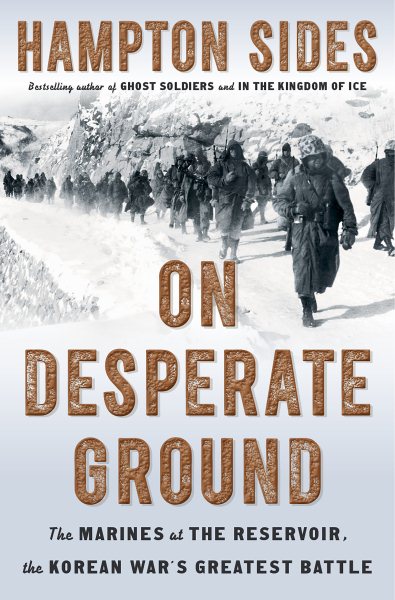

Though lesser known than other heroic military campaigns throughout America’s history, the struggle that played out along the frozen shores of the Chosin Reservoir in the snowy mountains of North Korea in 1950 tested the mettle of the First Marine Division beyond reason.