Surah CIX

The Disbelievers

As Revealed at Mecca

1: Say: O disbelievers!

2: I worship not that which ye worship;

3: Nor worship ye that I worship.

4: And I shall not worship that which ye worship.

5: Nor will ye worship that which I worship

6: Unto you your religion, and unto me my Religion

Are you a history buff interested in accounts of War—specifically moments like Pearl Harbor, the sinking of the Lusitania, or the Gulf of Tonkin incident? If you are, you must know the potent, practical knowledge of studying instances in which the USA has been forced to abandon ideals of isolation to wage war in foreign lands.

I have met professional and amateur historians that rattle off facts and stories about D-Day, Pearl Harbor, or the A-bombing of Japan as if they stood there with omniscience on each of those days—but I have met very few people that are receptive to the same, vivid discussion concerning what happened on 9/11.

I have met professional and amateur historians that rattle off facts and stories about D-Day, Pearl Harbor, or the A-bombing of Japan as if they stood there with omniscience on each of those days—but I have met very few people that are receptive to the same, vivid discussion concerning what happened on 9/11.

This is understandable; the wounds of 9/11 have hardly scabbed over. We still feel an emotional connection to the event and there is a collective seething just beneath the surface of our skins that makes objectivity an arduous pursuit. Alas, in order to channel our emotions toward greater resolution we must ready ourselves to have discussions with our peers without the fear of sounding “Un-American” or resorting to branded key words that numb our tongues and blind our vision.

As for many of the most difficult dilemmas, the Shelves of Lemuria may hold the answer.

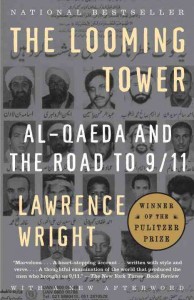

I had only begun to realize what happened on 9/11, and so six years after the towers fell I decided to buy a first edition copy of The Looming Tower by Lawrence Wright from Lemuria. Previously, it had been impressed upon me that the reason we were attacked was the product of an animosity driven by jealousy, silently brooding over seas, seething in envy of American ideals and freedoms.

The Looming Tower by Lawrence Wright exposed frailty and incongruence in my own perception of what happened on 9/11, 2001. The pages of this work armed me with a powerful weapon—understanding. Besides my own heartfelt praise, The Looming Tower has been internationally lauded as a must read by a myriad of authorities, and won the Pulitzer Prize. After finishing The Looming Tower I feel it is my civic duty to encourage you to read this book.

The Looming Tower by Lawrence Wright exposed frailty and incongruence in my own perception of what happened on 9/11, 2001. The pages of this work armed me with a powerful weapon—understanding. Besides my own heartfelt praise, The Looming Tower has been internationally lauded as a must read by a myriad of authorities, and won the Pulitzer Prize. After finishing The Looming Tower I feel it is my civic duty to encourage you to read this book.

Within the book, Wright makes poignant elaborations concerning the atmosphere that propelled the atrocities of 9/11. Much of The Looming Tower is spent analyzing Osama Bin Laden’s complex relationship with the West and with Saudi Arabia. An effort is spent to humanize Bin Laden and understand the importance of his exile from Saudi Arabia and the dual issuance of Fatwas against Saudi Arabia and the United States concerning the presence of an American military base on Islamic ground.

The Looming Tower makes the claim that Bin Laden’s expulsion from Saudi Arabia, where he was gaining traction as a populist mobilizer, led to his formation as an internationally sought financier and organizer of several grass roots extremist organizations. Bin Laden allowed the hunger for retribution corrupt his high levels of education and pervert his ideology towards gruesome ends. His thirst for vengeance upon the religious and political elites of Saudi Arabia catalyzed his momentum towards the violent culmination of 9/11.

Bin Laden’s motive as shown in The Looming Tower for organizing the hijackings of 9/11 was a strategic maneuver of wicked guile. He wished to strike the Saudi government, but found his organizations’ numbers too small to carry out such an audacious move—so he did the one thing that would become the legacy of the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan: improvisation.

The lesson applied to The Looming Tower explains to me why Bin Laden attacked America in the first place. The thousands in the Towers, on the planes, and working in the pentagon were doves—completely innocent to motives and intentions of Bin Laden. The American Air Force, being the metaphoric red-tailed hawks theoretically would have become hungry for large meals of the religious and political elite of Saudi Arabia (being the metaphoric timber rattlers).

The stratagem was quite simple: attack Saudi Arabia by proxy. Al-Qaeda casted the 9/11 hijackers nearly exclusively from Saudi Arabia in order to illicit a violent response toward Saudi Arabia from the US. The intent of this design was to make it appear that the attack originated from Salafist and Wahhabi communities within Saudi Arabia, which (in thought) would propel America to employ their tools of war upon the political and religious infrastructure of Saudi Arabia. Perhaps, this could’ve happened if it weren’t for the hard work of our intelligence officers, who understood that the Taliban was housing Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan.

If you haven’t read a well researched, objective account on Al-Qaeda or extremism in general, The Looming Tower is the best place to start. Come to Lemuria, put the book in your hands and feel the historical proximity of yourself to Wright’s work. Open it, let your emotions flow as the pages turn and you will connect to this book immediately. Then the next step should come naturally: tell others how you feel and what you think should be the next step in “The War on Terror.”

Photo Credit: http://www.dailymail.co.uk