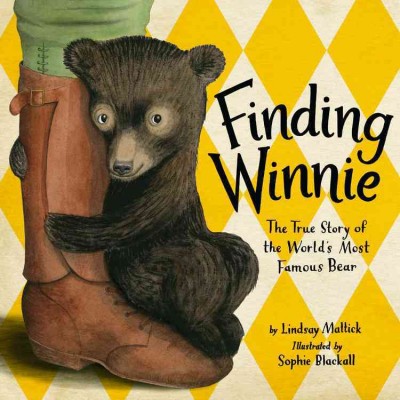

On August 24, 1914, Captain Harry Colebourn bought a baby bear for $20 on a train station platform.

“Harry stopped. It’s not every day that you see a bear cub at a train station. ‘That Bear has lost its mother,’ he thought, ‘and that man must be the trapper who got her.’”

On his way overseas to fight in World War I, Colebourn, a veterinarian from Winnipeg, decided to name the bear Winnie after his hometown.

When Colebourn showed Winnie to the Colonel, he was originally met with disapproval.

“’Captain Colebourn!’ said the Colonel on the train, as the little Bear sniffed at his knees. ‘We are on a journey of a thousand miles, heading into the thick of battle, and you propose to bring this Most Dangerous Creature?’ Bear stood straight up on her hind legs as if to salute the Colonel. The Colonel stopped speaking at once—and then, in quite a different voice, he said, ‘Oh, hallo.’”

Soon, Winnie was one of their own.

Finding Winnie is narrated by Lindsay Mattick, the great-grandaughter of Harry Colebourn, as a family story passed down from generation to generation. When Lindsay’s son asks her for a story, she asks “What kind of story?” to which the reply is;“You know. A true story. One about a Bear.”

Finding Winnie is narrated by Lindsay Mattick, the great-grandaughter of Harry Colebourn, as a family story passed down from generation to generation. When Lindsay’s son asks her for a story, she asks “What kind of story?” to which the reply is;“You know. A true story. One about a Bear.”

This picture book tells the miraculous journey of a man and his bear that crossed the Atlantic from Canada to England; and this is the very bear that would become the inspiration for Winnie-the-Pooh when A.A. Milne and his son visited the London Zoo.

After crossing the Atlantic with Winnie, Harry knew that she was growing larger and could not be taken into battle, so he took her to the London Zoo.

“Winnie’s head bowed. Harry’s hands were warm as sunshine, as usual. ‘There is something you must always remember,’ Harry said. ‘It’s the most important thing, really. Even if we’re apart, I’ll always love you. You’ll always be my Bear.’”

Harry and Winnie’s parting seem’s like the end of the story, but as Lindsay points out, “Sometimes, you have to let one story begin so the next one can begin.”

The beautiful and heartfelt illustrations by Sophie Blackall bring this story to life in ink and watercolor. Her illustrations depict Harry Colebourn’s excitement of finding the bear, the heartache of leaving Winnie behind in the zoo, and the joy of a new friendship with Christopher Robin. Finding Winnie will bring you and your child joy and delight at discovering the true story behind one of the most famous characters in literature, and show that sometimes, one story’s ending is just another story’s beginning.

China Miéville’s newest work,

China Miéville’s newest work,

For the first time in a while, certainly all year, I am unsure of what to make of a book.

For the first time in a while, certainly all year, I am unsure of what to make of a book.

This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about

This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about

So I don’t think I will win over many people by saying that

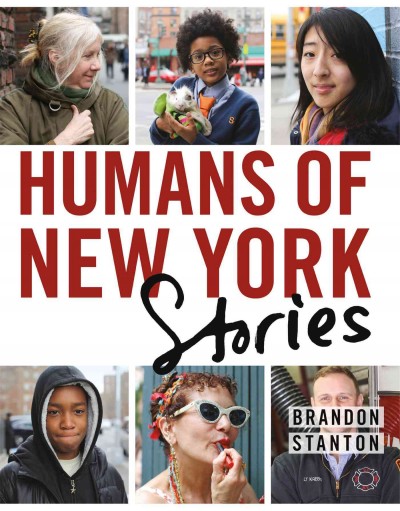

So I don’t think I will win over many people by saying that  It seems impossible to be able to capture what it is to be human, but Brandon Stanton has come pretty darn close.

It seems impossible to be able to capture what it is to be human, but Brandon Stanton has come pretty darn close.