Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (February 18)

Longtime friends Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett, who both spent childhood years in Jackson, give readers an unexpected and fresh look at their hometown city’s history through 20 mostly never-before-told stories that bring to life the “Hidden History of Jackson.”

Longtime friends Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett, who both spent childhood years in Jackson, give readers an unexpected and fresh look at their hometown city’s history through 20 mostly never-before-told stories that bring to life the “Hidden History of Jackson.”

The collection, published by Arcadia Publishing, includes tales of horror and heroism dating back to the 1700s, and touches on Indian mounds, land pirates, frontier life, wartimes, the civil rights movement, school integration, music legends, epidemics, “the Greater University that never was,” and more.

Josh Foreman

Foreman grew up in Jackson, Ridgeland, and “the Rankin County side of the Reservoir.” After earning a Bachelor of Arts degree from Mississippi State University in 2005, he left for a teaching job in South Korea, and remained there for nine years. In 2014, he returned to the U.S. and enrolled in the University of New Hampshire’s Mater of Fine Arts in Writing program. Now a teacher at St. Stanislaus College in Bay St. Louis, he and his wife Melissa make their home there with their children Keeland and Genevieve.

Ryan Starrett

Starrett was born and reared in Jackson. After a 10-years hiatus in Texas, and degrees from the University of Dallas, Adams State University, and Spring Hill College, he returned home to continue teaching at St. Joseph Catholic School in Madison. He and his wife Jackie live there with their children, Joseph Padraic and Penelope Rose O. Starrett.

How did it come about that you two had the opportunity to write Hidden History of Jackson, one in the “Hidden History” series published by The History Press?

Starrett: I completed a degree with a thesis on the integration of the Catholic diocese of Jackson and submitted my work to the History Press hoping it might be published. Ms. Amanda Irle thought differently. She suggested writing a broader history of Jackson.

Disappointed, I dismissed the idea, until several months later when my oldest friend Josh and I met up at Broad Street (Baking Co.) for brunch. We had recently read Richard Grant’s Dispatches From Pluto, and decided to pay our respects to the man who had written so honestly and beautifully about an underappreciated corner of Mississippi. We bought a bottle of whiskey and drove to his house expecting to drop it off and hoping we could deliver a quick “thank-you.” Lo and behold, his wife answered the door and said Mr. Grant was not at home, but told us to wait; she would call him and he’d be home shortly. Ten minutes later, he arrived and proceeded to invite us strangers into his house and graciously spoke with us for half an hour.

When Josh and I left, we drove to Cups and determined that we would try our best to tell the story of Jackson the way Mr. Grant wrote of the Delta. We then jointly submitted a table of contents and synopsis of a new proposal to Ms. Amanda Irle. This time, she enthusiastically championed our proposal and we were contracted to write The Hidden History of Jackson.

Hidden History of Jackson is described as a collection of “20 little-known stories from the history of Jackson,” dating from the 1700s. How did you choose the stories included here and how did you find out about them?

Foreman: Ryan and I first began to make a chapter outline sitting in his backyard in Ridgeland. We started out knowing we wanted to tell certain stories–the true story of Louis LaFleur and the story of Derek Singleton’s integration of St. Joe, to name a couple. We stuck to the original chapter outline to an extent, but many of the stories we ended up telling emerged from the research as the process moved along.

The story of T.F. and Kate Decell is a good example of a chapter that grew organically. WE had originally planned tow rite about vigilante justice in Jackson’s early days. I stumbled on the story of the Decells in old newspapers, and their saga incorporated so many themes from frontier Jackson–the pursuit of riches, alcohol abuse, violence, vigilante justice. Kate emerged from the story as a symbol of toughness, persistence, and hope–a good inspiration for the city.

Tell me about your exhaustive research for this project. How long did it take you to complete this book?

Starrett: Josh and I are incredibly fortunate to be writers in 2018. The research tools available now are unbelievable. Digitalized sources such as newspapers.com and thousands of documents and diaries that have been transcribed and uploaded by archivists throughout the country all made research relatively easy compared to what historians just a decade or two ago had to go through.

In spite of all the tools that seemingly fell into our laps, we never would have been able to complete this project without those who came before us and who traveled to archives, visited historic sights, and conducted exhaustive interviews. Without their work, and without the work of countless archivists and historians, we simply would not have had the tools to put together the Hidden History of Jackson.

Briefly, could you mention two or three stories that were among your favorites?

Foreman: I mentioned the Decell story before–that was definitely one of my favorites. The story was just there in old newspaper articles and court records, waiting to be told, and we were lucky enough to be the first–that I know of–to tell it.

Another subject I enjoyed researching was the creation and naming of the Ross Barnett Reservoir. I spent much of my childhood on the Rez, and as I’ve gotten older the fact that it is named after our former segregationist governor has really bothered me. Obtaining the minutes from the Pearl River Valley Water Supply District meeting when the board decided to name the reservoir after Barnett was satisfying because it showed that the decision was never made in good faith. It was satisfying to tell a more thorough side of the story and to say, with research, that the Rez should never have been named after Barnett.

The chapter about the Nazi generals imprisoned at Camp Clinton really blew my mind. I had no idea before we began researching that some of the highest-ranking Nazi generals spent much of World War II as prisoners in Clinton, and that they sometimes escaped and made their way downtown, undetected, for supper before heading back to camp.

Starrett: Aside from the interviews we conducted, I enjoyed researching the Sisters of Mercy and their service to Jackson as teachers and nurses. I expected to read about saintly women who offered their lives to the service of the poor, sick, uneducated and dying, at great risk to themselves; that is exactly what I found. What I had not expected was to see them as innately human. Teilhard de Chardin claims that “joy is the most infallible sign of the presence of God,” and these nuns radiated that joy. They mostly lived under wretched conditions–especially during the Civil War years. They were surrounded by the poor, the uneducated, the sick, and death was always in their midst. Yet, these sisters maintained their sense of service and humor. They were also some of the toughest people I came across while researching the book. They were a feisty, joyful group who made a lasting impact on the history of Jackson.

Since you’re both originally from Jackson, what did you enjoy most about this project, and what did you enjoy most about this project, and what did you find to be most challenging about it?

Starrett: I think the most enjoyable part for me would be the interviews we conducted with Tommy Crouch and Derek Singleton. Mr. Couch is a local mogul. For more than half a century, he has been creating and promoting music right here in Jackson. His company, Malaco Records, is still on Northside Drive and has produced a number of iconic albums. The fact that he believed in and invested his life’s work in his community was rewarded by his company’s success. All you need to do is step into his offices and you’re almost overwhelmed by the hit records and posters covering the wall from internationally known musicians.

Mr. Singleton, likewise, is a Jackson hero. Growing up in Mississippi, I knew the names of Medgar Evers, James Meredith, and a handful of other local civil rights activists. Yet, Mr. Singleton, and his mother, deserve to be remembered, too. He was the first man to integrate St. Joseph school, which in turn was the first high school in the state to integrate. Thus, he is the quiet, humble man who broke down the color barrier in Mississippi’s schools.

The opportunity to learn from men like Mr. Couch and Mr. Singleton, as well as to learn from more than a dozen other now deceased Jacksonians through their memoirs, newspaper clippings, diaries, census records, and other documents made writing the Hidden History of Jackson an incredible joy and blessing.

Foreman: I was lucky enough to have a few months off between finishing grad school at UNH and starting my teaching job in Bay St. Louis. I spent most of that time researching and writing. It was a great joy to be able to wake up in the morning, brew a pot of coffee, sit down at my computer, and just research for hours. I love the research process and how stories can take shape with each old newspaper article or document you read through. I’d call Ryan every day and tell him about what I’d discovered–“You’re never going to believe this–the city of Jackson was planned by Thomas Jefferson!”–and he’d tell me about what he’d found.

I have to give a huge shout out to my wife, Melissa, here–she was willing to take care of our two kids, Keeland and Genevieve–during those long stretches I spent writing and researching at the computer. She has been extremely supportive.

The hardest thing about the whole process for me was just digging into the ugly side of Jackson’s history. It was painful reading about the brutality in Jackson’s past–the chapter on runaway slaves was particularly difficult to research and write. Learning the story of James Brown, a black man who was arrested in Madison County in 1832, imprisoned and likely sold into slavery, was heartbreaking. The only document that exists telling Brown’s story is an old runaway slave advertisement that was published after his arrest. Brown told authorities he was a free riverboat worker from New York City, which was entirely possible. But the law functioned in such a way that even free blacks were easily deprived of their freedom.

We couldn’t figure out whether Brown was ever freed or whether he spent the rest of his life in bondage. It was so sad to read about a man trapped in such a cruel system. Jackson has a tragic heritage in many respects, but I believe facing the reality of our past in an important step in making a better future.

Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett will be at Lemuria on Saturday, February 24, at 1:00 p.m. to sign copies of Hidden History of Jackson.

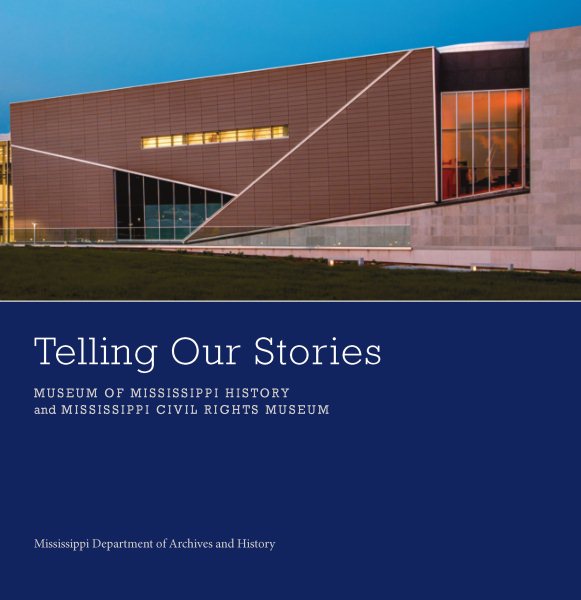

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

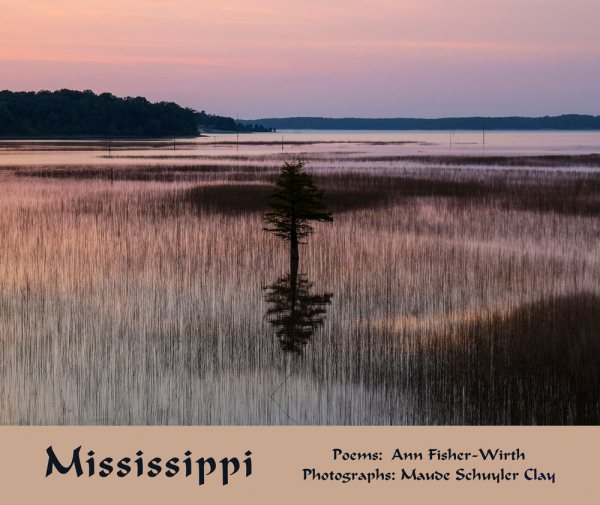

Her newest book, titled

Her newest book, titled

The initial idea grew out of my fascination with two historical events: the series of unsolved ax murders that reached its culmination with a bizarre letter to the Times-Picayune; and the excavation of the Industrial Canal, a hubristic manhandling of the local terrain that has haunted New Orleans ever since.

The initial idea grew out of my fascination with two historical events: the series of unsolved ax murders that reached its culmination with a bizarre letter to the Times-Picayune; and the excavation of the Industrial Canal, a hubristic manhandling of the local terrain that has haunted New Orleans ever since.

I believe each of them is stronger than he initially thinks is the aftermath of that tragedy. Richard is a naturally skilled writer, and those abilities, along with a lifetime of trying to do an honest job as a reporter, eventually re-involve him in life.

I believe each of them is stronger than he initially thinks is the aftermath of that tragedy. Richard is a naturally skilled writer, and those abilities, along with a lifetime of trying to do an honest job as a reporter, eventually re-involve him in life. Jamie Quatro’s debut novel,

Jamie Quatro’s debut novel,

The book, which documents the obvious racial injustice with which the case was handled by local officials, gained national attention because of the eccentric lifestyle of initial suspects Richard Dana and Octavia Dockery, who lived in a decaying antebellum home overrun with crumbling furnishings, pervasive filth–and a pen of goats, among many other animals.

The book, which documents the obvious racial injustice with which the case was handled by local officials, gained national attention because of the eccentric lifestyle of initial suspects Richard Dana and Octavia Dockery, who lived in a decaying antebellum home overrun with crumbling furnishings, pervasive filth–and a pen of goats, among many other animals.

Johnny, a poor, kind, young boy, is forced one day by his cruel grandfather to sell his pet chicken at the market. In doing so, he unexpectedly comes into possession of some magical seeds. From the seeds grow a flower, and upon eating the flower, Johnny is granted the ability to speak with animals. Led by a skunk named Susy, Johnny and all the animals in the land set out on a quest to rescue a stolen prince, and with some luck, perhaps cross paths with a familiar chicken.

Johnny, a poor, kind, young boy, is forced one day by his cruel grandfather to sell his pet chicken at the market. In doing so, he unexpectedly comes into possession of some magical seeds. From the seeds grow a flower, and upon eating the flower, Johnny is granted the ability to speak with animals. Led by a skunk named Susy, Johnny and all the animals in the land set out on a quest to rescue a stolen prince, and with some luck, perhaps cross paths with a familiar chicken. This story began as a piece of oral tradition. It was as a story told out loud, maybe over the course of several nights by an adult to children. I would hope the finished book is used in much the same way. While the language might be difficult for a child under the age of 9 or 10, I believe that children of all ages will be able to appreciate the story–its rhythm, its humor, and its message–especially when told directly to them by a parent, or grandparent, or some other important adult figure in their life.

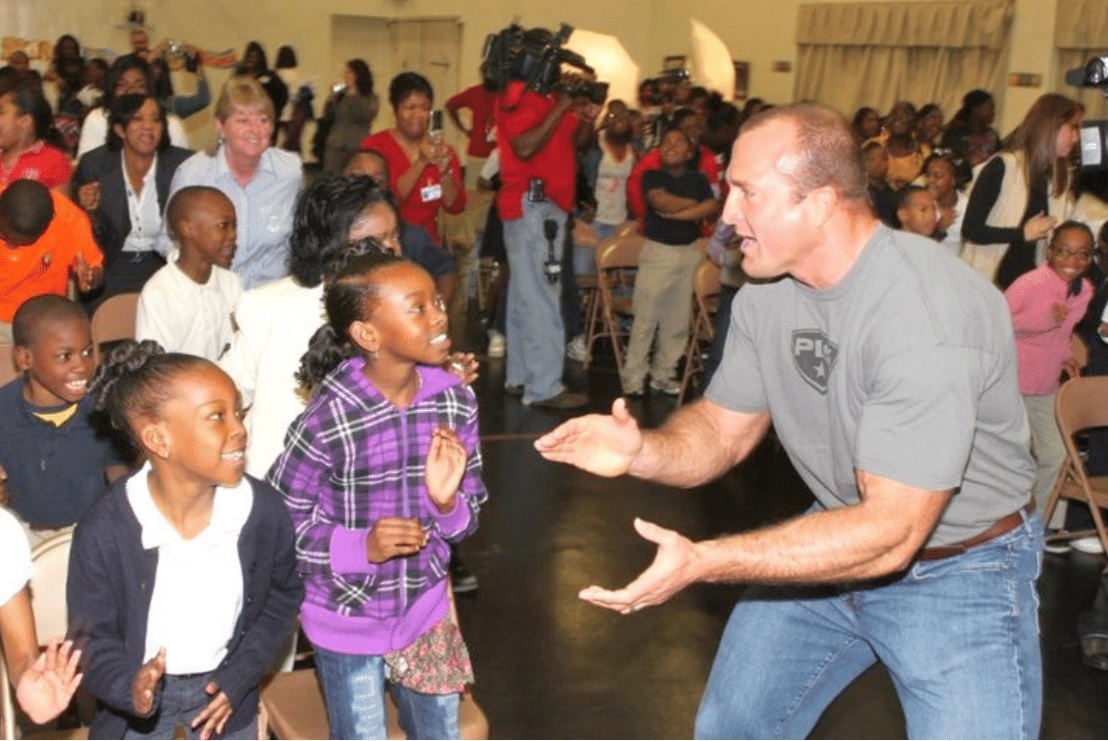

This story began as a piece of oral tradition. It was as a story told out loud, maybe over the course of several nights by an adult to children. I would hope the finished book is used in much the same way. While the language might be difficult for a child under the age of 9 or 10, I believe that children of all ages will be able to appreciate the story–its rhythm, its humor, and its message–especially when told directly to them by a parent, or grandparent, or some other important adult figure in their life. Paul Lacoste has spent his career coaching others into top physical form, and he’ll be the first to admit that when it comes to getting his clients in shape, he’s not known for taking a subtle approach.

Paul Lacoste has spent his career coaching others into top physical form, and he’ll be the first to admit that when it comes to getting his clients in shape, he’s not known for taking a subtle approach.

In

In