By Andrew Hedglin. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (April 14)

Angie Thomas created a cultural phenomenon from Jackson to Hollywood two years ago with her debut, The Hate U Give, a young-adult novel about the aftermath of a police shooting of an unarmed black teenager. However, the book contains so much more than that, from the coming-of-age tale of protagonist Starr Carter, to its beautiful, real depictions of life in a black community.

Thomas returns to the fictional Garden Heights community of The Hate U Give in her follow-up novel, On the Come Up. In this book, 16-year-old Bri Jackson overcomes other people’s expectations for her to find her voice and use her talent for hip-hop to communicate her place in the world. From the “ring battles” in a local boxing gym to the SoundCloud-inspired accounts of the internet, Bri always goes forth boldly to remind the world that “when you say brilliant that you’re also saying Bri.”

Thomas returns to the fictional Garden Heights community of The Hate U Give in her follow-up novel, On the Come Up. In this book, 16-year-old Bri Jackson overcomes other people’s expectations for her to find her voice and use her talent for hip-hop to communicate her place in the world. From the “ring battles” in a local boxing gym to the SoundCloud-inspired accounts of the internet, Bri always goes forth boldly to remind the world that “when you say brilliant that you’re also saying Bri.”

Part of those expectations are from people in her community expecting her to carry the mantle of her father, the underground hip-hop legend Lawless, who was tragically murdered when Bri was a child. Bri is proud of her father’s legacy, but she has her own unique experiences to share.

The other side of the expectations is weighted with racial anxiety. Bri attends an arts-based magnet school in the posh Midtown neighborhood, bused there every day with her friends Sonny, anxious about grades and his online crush on a neighborhood boy, and Malik, her other best friend, her secret crush, and a budding political activist.

When Bri is stopped by security guards while smuggling contraband snacks into school, an ugly incident takes place in which she is forcefully pinned to the ground by security guards with a history of racial profiling. The cell phone videos of the incident have the power to reveal the truth of what happened, but they also have the power to distort. The image imparted partially depends on what the viewer wants, or expects, to see in the first place.

So it is with the lyrics to the song that Bri records in response to the incident, called “On the Come Up.” Students use the song in a school protest that goes wrong. A local DJ baits Bri in a radio interview, because Bri, while talented and thoughtful, is often prone to emotional, hot-headed responses. Bri laces her song with plenty of irony and nuance, yet those meanings are sometimes hard to convey in a song that’s also catchy enough to become a viral hit.

Meanwhile, Bri has to make important decisions, including her choice of manager. Should she stick with her beloved Aunt Pooh, a gangsta with a heart of gold and amateur to the business? Or should she side with Supreme, her father’s old shark-like manager with opaque motivations?

Bri is vulnerable to being sorely tempted to temper her image to achieve success. Self-expression is fine for what it’s worth, but real financial pressures await at home when her single mother is laid off from her job as a church secretary in the aftermath of the riots from The Hate U Give.

Her mother Jay and her brother Trey tell her not to worry, that she shouldn’t make long-term decisions based on immediate financial circumstances, but Trey has already put grad school on hold, and Jay has a history of not always being there for them, including a long stretch of drug addiction after their father and her husband was murdered in front of her.

In addition to this mesmerizing world-building, Thomas carries her spirited first-person narration into this new tale. Thomas does a very fine job balancing the personal and the political. Her style and solid writing will appeal not just to young fans who see themselves represented, but to older fans as well who wish to peek into the world a young, vibrant world populated with strong, three-dimensional black characters.

Andrew Hedglin is a bookseller at Lemuria Books, a graduate of Belhaven University, and a lifelong Jackson resident.

Signed copies of Angie Thomas’s books are available at Lemuria and on its web store.

That curiosity eventually led to published research in newspapers, magazine, website, and blogs about the role of women in the Civil War.

That curiosity eventually led to published research in newspapers, magazine, website, and blogs about the role of women in the Civil War.

In her latest novel,

In her latest novel,

For a seemingly demure and grandmotherly-type lady, Janet Brown knows how to scare the crud out of you. Her fourth thriller,

For a seemingly demure and grandmotherly-type lady, Janet Brown knows how to scare the crud out of you. Her fourth thriller,  In his first book,

In his first book,

In a fast-paced page-turner, Philip Shirley weaves a tale of intrigue and nation-jumping that renews the debate over Elvis in the mystery novel

In a fast-paced page-turner, Philip Shirley weaves a tale of intrigue and nation-jumping that renews the debate over Elvis in the mystery novel  I once heard that suspense in a work of fiction should feel like watching a balloon expand steadily. Each detail, each new turn or development in the plot should function like another breath going in, applying another ounce of pressure as the skin swells and grows taut until at last it reaches the breaking point.

I once heard that suspense in a work of fiction should feel like watching a balloon expand steadily. Each detail, each new turn or development in the plot should function like another breath going in, applying another ounce of pressure as the skin swells and grows taut until at last it reaches the breaking point. New York Times bestselling author Tom Clavin adds to his collection of historical nonfiction with

New York Times bestselling author Tom Clavin adds to his collection of historical nonfiction with

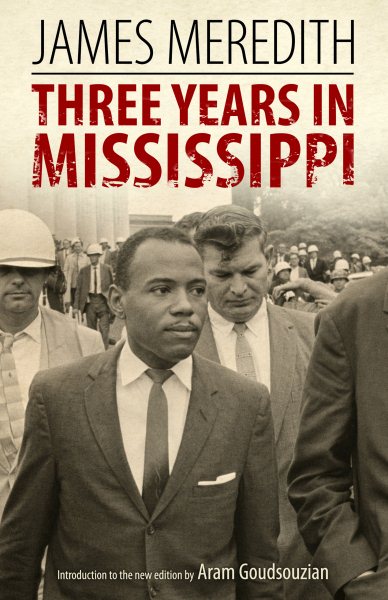

Famous for integrating the University of Mississippi in 1962, Meredith has been a challenging and criticizing voice in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi ever since. In some ways, Meredith started it all in his home state, and he documented that struggle in his first book

Famous for integrating the University of Mississippi in 1962, Meredith has been a challenging and criticizing voice in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi ever since. In some ways, Meredith started it all in his home state, and he documented that struggle in his first book