Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (December 17)

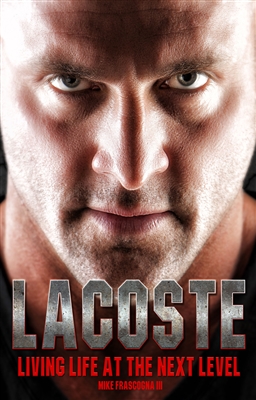

Paul Lacoste has spent his career coaching others into top physical form, and he’ll be the first to admit that when it comes to getting his clients in shape, he’s not known for taking a subtle approach.

Paul Lacoste has spent his career coaching others into top physical form, and he’ll be the first to admit that when it comes to getting his clients in shape, he’s not known for taking a subtle approach.

But he’s learned the hard way that motivating people to reach their fitness goals is about more than changing their physical appearance–it’s all about inspiring mental and spiritual changes, as well.

In his newly released book, Lacoste: Living Life at the Next Level, he shares his own story of how the many life challenges he’s faced eventually led to a realization that only his faith in God could turn things around.

Today Lacoste, who holds a master’s degree in Sports Administration from Mississippi State University, enthusiastically brings that commitment to his coaching style, as he tells clients: “I want your F.A.T.”–or Fears Affecting Transformation. His goal these days is to go beyond their physical needs as he acknowledges that they, like him, may be facing inner challenges that could hold them back from reaching fitness objectives.

A lifelong athlete who was named an All SEC football player at MSU and played for the National Football League, the Canadian Football League, and the XFL, Lacoste found that it was adversity–not athleticism–that would lead him to the next level.

His growing series of nationally recognized fitness programs for adults, students and pro athletes has brought him scores of awards, including the White House Champions of Change award and several designations as best trainer in the Jackson Metro area.

Mike Frascogna III, who competed against him in high school sports and played college football at Notre Dame while Lacoste played at Mississippi State, is an intellectual property lawyer and co-author of five previous sports-related books. Lacoste: Living Life at the Next Level, he says, is a result of his 30-year friendship with Lacoste.

As the youngest of four competitive, athletic, and smart brothers and the son of a very driven father, you grew up in Jackson in a home you’ve described as loving, supportive, and extremely competitive. Briefly explain the values that were instilled in you through those years.

Growing up in a home that demonstrated tremendous love, support, and extreme competition fortunately taught me the values of what true love, protection, and lifelong commitment is for family, friends, and loved ones. More specifically, I learned by observation and watching my parents’ actions towards each other and towards each of their children. We were all taught we could achieve and do anything we wanted if we stayed focused, worked hard, and never gave up on the goals and dreams life set before us.

Encouraging health and wellness at a local elementary school

Along with this, I was taught to not grow up and find “any job” just to bring home a paycheck, but to truly find something I was passionate about–and that success was sure to follow. This is something I have personally carried on and try to instill in my two sons, Cannon and Cole, on a daily basis.

As you grew, you realized you were blessed with athletic talent and, thanks to your mother, you also excelled academically despite the challenges of hyperactivity and dyslexia. How have these realities shaped you?

Growing up with ADHD and dyslexia combined, I had to quickly learn the importance of a serious work ethic at a young age. I treated my football days as my job from junior high forward. With this, I had to choose to overcome obstacles, never back down, and know hard work was sure to pay off.

Looking back, I am forever thankful for my mother’s consistency in working with me every day, and for choosing to not let my “fits” as a kid cause her to give in and not make me complete what she knew was best for me.

Those realities have brought me through so many obstacles and so many stages in my life, including my brother’s death at a very young age, accepting the highs and lows of my football career, overcoming West Nile, and facing a terrible divorce, to name a few.

After being named an All-SEC player at Mississippi State and participating in brief associations with the NFL, the CFL and the XFL, you earned your master’s degree in Sports Administration, began to reconsider your dream of playing pro ball, and planned to begin a career in coaching. It turned out that you found your niche in fitness training for mostly non-athletes. How and why did this turn out to be your most passionate career pursuit?

I consider my niche to be more of a “coaching” style rather than a fitness training approach. Whether I am working with a pro athlete getting ready for the combine or a local business man or woman, my goal is to help that person achieve his or her dreams and to never give up.

Early morning training at Madison Central High School

I give a lot of credit for the way I coach today to my mother and the way she worked with me as a young boy, and to my coaches in football, basketball, soccer, and other sports, throughout life.

My passion lies in helping people take life to the next level. Yes, my clients come to me to get in shape. However, I have learned that getting in shape is not just physical. I tell my clients, “I want your F.A.T.!”

“FAT” stands for fears affecting transformation. These fears can be physical, spiritual, and mental–anything that holds an individual back from being his or her best.

It seems the word most associated with your training style (and everything else you do) is “intense,” and you developed a reputation as a somewhat ruthless trainer who produced results for clients, but often with a rather “rough around the edges” persona. You’ve lightened up in recent years. Explain the change.

I have definitely not “lightened up.” I am still just as intense, if not even more passionate now than ever. But through the trials and tribulations previously mentioned it became clearer to me in recent years what “F.A.T.” consisted of. Through the valleys and mountains in my own life, I can better relate to my clients and what is holding them back. Getting baptized on my 40th birthday started a new beginning for me.

You still demand a lot of your clients when they sign up for your training programs. Tell me about the programs you offer, and what clients can expect.

Currently, I have three 12-week programs a year; three four-week programs; and the Fit 4 Series, consisting of Fit 4 Change, Fit 4 Preaching, Fit 4 Teaching, and Fit 4 Healthcare. The 12-week programs and Fit 4 programs are four days a week for an hour each day. The four-week programs take place on the “off months” of the 12-week programs, meeting twice a week for an hour each day.

I make it clear to all participants on day one of each program that I have them for one hour a day and there are 23 more hours in the day, leaving it up to each of them to have discipline and stay focused. During this one hour it is very important that the participants don’t waste their time or my time by stepping onto the training field if they are not ready to give it their all.

All in all, clients can expect results through a training program that is recognized and has been recognized for years as not only as intense, but as the best throughout the country. Paul Lacoste Sports has been contacted by the Oprah Winfrey Network, presented with the award for excellence in wellness promotion by the Mississippi State Medical Association, nominated for the Magnolia award and for the White House Champions of Change award featured in Men’s Health Magazine, and voted as best boot camp and trainer in the Greater Jackson area, to name a few.

Why did you decide to put your story into book form?

My longtime life friend Mike Frascogna has encouraged me for years to consider a book that would offer inspiration and motivation to anyone who is wanting to know he or she is not alone in overcoming the obstacles, trials and tribulations that life has to offer at all stages. Mike has been by my side for over 20 years, and has lived through challenging personal life events with me. Through his persistent encouragement, Mike made it clear to me that if I shared my life struggles with others, the story would be worth it 100 times over and over again if it saved one person from giving up on life’s dreams, passions, and the unique talents and abilities God has blessed each of us with.

Just as important, my dear friend and mentor Ron Aldridge with the Mississippi Beverage Association has stood by my side through thick and thin since the first Fit 4 Change program in 2009. It was with his shared passion for the health and wellness for the state of Mississippi that he has not only encouraged me, but made the book become a reality through our business partnership.

Through the years, you’ve endured the crushing weight of adversity through the death of your oldest brother when he was only 28, financial setbacks, divorce, a life-threatening case of West Nile virus, cancer, depression, and the threat of losing your two young sons. What has transformed your outlook into a more positive attitude?

Once my ex-wife moved my sons away from me from Madison to the Gulf Coast, making it nearly impossible for me to have a daily relationship with Cannon and Cole, I was quickly knocked down and felt I had nowhere else to go.

At that point, I opened my hands and asked God to take full control of my life and lead the way. I learned the hard way we all have “our” plans for our lives, but God’s plan is much better, even though it may be a different plan than what we expected. We must choose to trust in Him. Our minister at Pinelake [Church] told us that “If we give our future to God, we get a future.” Wow, now that’s powerful!

A new approach to training

What does your future hold?

Just around the corner, Fit 4 Change and Fit 4 Preaching will take place in January, February, and March. I am looking forward to Fit 4 Healthcare and Fit 4 Teaching during the summer months. I continue to strive in looking for new opportunities and programs that will positively impact the health and well-being not only for our local community but throughout the state of Mississippi.

Paul Lacoste and Mike Frascogna III will sign copies of Lacoste: Living Life at the Next Level at 5 p.m. Dec. 20 at Lemuria Books in Jackson.

In

In

What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

A little girl with shining hair helping rogue bandits in the dark forest of the Hinterlands, discovering her magic while escaping the evil Townies who killed her mother for being a witch, Jimmy Cajoleas’ book

A little girl with shining hair helping rogue bandits in the dark forest of the Hinterlands, discovering her magic while escaping the evil Townies who killed her mother for being a witch, Jimmy Cajoleas’ book

You’ve enjoyed a full life — world traveler, family man, would-be farm hand and at times you’ve turned your attention to politics (mostly through your deep interest in policy), journalism, the military, and your own formal education, not to mention an amazing career as a writer. How have you managed to fit so many interests into your seven decades?

You’ve enjoyed a full life — world traveler, family man, would-be farm hand and at times you’ve turned your attention to politics (mostly through your deep interest in policy), journalism, the military, and your own formal education, not to mention an amazing career as a writer. How have you managed to fit so many interests into your seven decades? Your newest book, “Paris in the Present Tense,” is another fictional work presented on a grand scale. In this story of an aging man consumed with worry about his grandson’s serious illness, main character Jules Lacour is keenly aware of his own inability to offer much in the way of financial support. A deep thinker with strong convictions, he looks back on his own life with his share of regrets and fears. In many ways, most of us have a lot in common with Lacour. Can you share your reflections on him?

Your newest book, “Paris in the Present Tense,” is another fictional work presented on a grand scale. In this story of an aging man consumed with worry about his grandson’s serious illness, main character Jules Lacour is keenly aware of his own inability to offer much in the way of financial support. A deep thinker with strong convictions, he looks back on his own life with his share of regrets and fears. In many ways, most of us have a lot in common with Lacour. Can you share your reflections on him?  Cultural and economic historian Gene Dattel, who grew up in the small Mississippi Delta town of Ruleville, tackles questions about what he calls “America’s most intractable problem–race”–up close and in depth in his newest book,

Cultural and economic historian Gene Dattel, who grew up in the small Mississippi Delta town of Ruleville, tackles questions about what he calls “America’s most intractable problem–race”–up close and in depth in his newest book,

The micro-memoir, she has said, “combines the extreme abbreviation of poetry, the narrative tension of fiction, and the truth-telling of creative nonfiction,” in works that include “memories, quirky observations, tiny scenes, (and) bits of overheard conversations that, with the surrounding noise edited out, reverberate.”

The micro-memoir, she has said, “combines the extreme abbreviation of poetry, the narrative tension of fiction, and the truth-telling of creative nonfiction,” in works that include “memories, quirky observations, tiny scenes, (and) bits of overheard conversations that, with the surrounding noise edited out, reverberate.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jennifer Egan’s newest release

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jennifer Egan’s newest release

It’s nice of you to ask. And, I promise you, I’m truly thankful for the people who invest in reading this novel once–that’s already a gift for a writer, and I ask no more. I can tell you that I worked hard to build a book you could just sit down and read, a linear novel that also happens to wrestle with age-old conflict and has many different plot lines, all running concurrently.

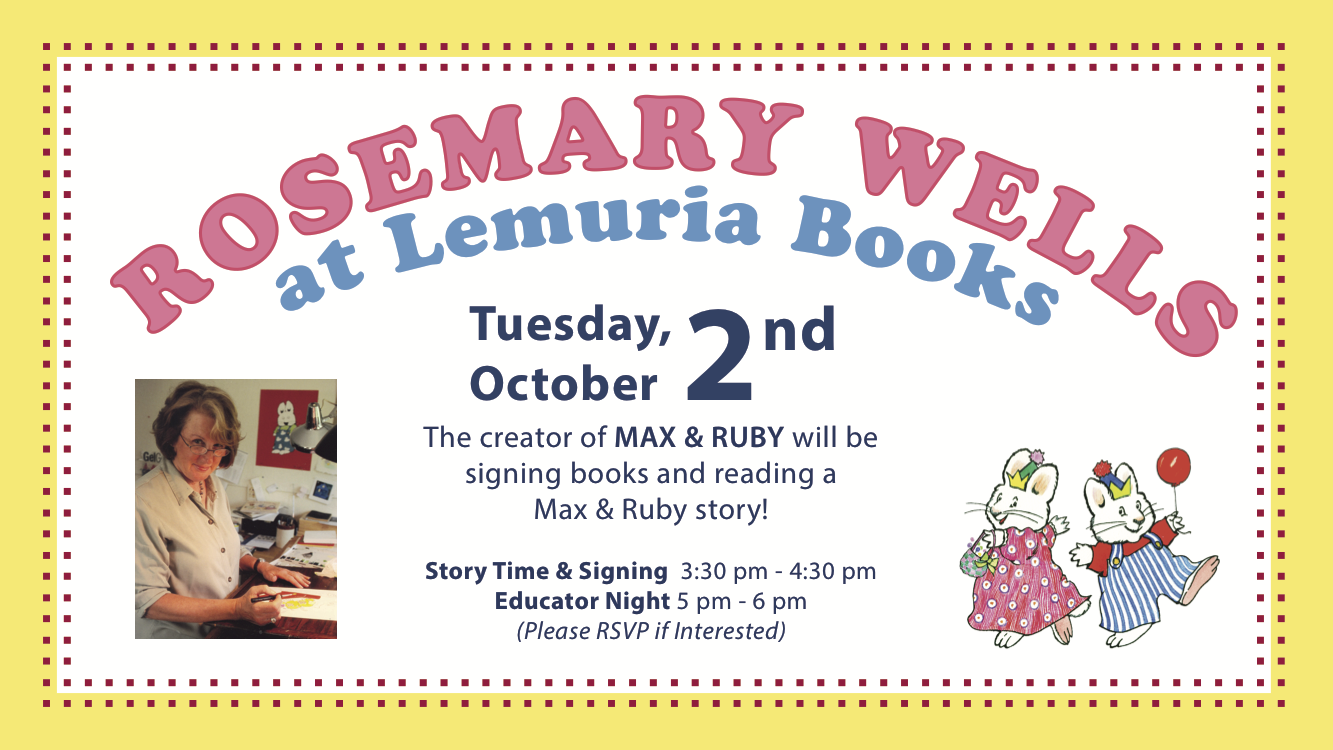

It’s nice of you to ask. And, I promise you, I’m truly thankful for the people who invest in reading this novel once–that’s already a gift for a writer, and I ask no more. I can tell you that I worked hard to build a book you could just sit down and read, a linear novel that also happens to wrestle with age-old conflict and has many different plot lines, all running concurrently. Their creator, Rosemary Wells, has been writing and illustrating books for over 45 years. She began working in publishing as a book designer for seven years. All through her writing and illustrating career, from her picture books to her young adult novels, Rosemary Wells advocates for children’s literacy wherever she goes. Born in New York City and raised in rural New Jersey, she now resides in Connecticut.

Their creator, Rosemary Wells, has been writing and illustrating books for over 45 years. She began working in publishing as a book designer for seven years. All through her writing and illustrating career, from her picture books to her young adult novels, Rosemary Wells advocates for children’s literacy wherever she goes. Born in New York City and raised in rural New Jersey, she now resides in Connecticut. My equally favorite character is Yoko. My next book is another Felix and Fiona melodrama friendship book from Candlewick. And next year, I have a book from Macmillan that introduces new characters, Kit and Kaboodle, twin pussycats and their little nemesis, Spinka, the mouse.

My equally favorite character is Yoko. My next book is another Felix and Fiona melodrama friendship book from Candlewick. And next year, I have a book from Macmillan that introduces new characters, Kit and Kaboodle, twin pussycats and their little nemesis, Spinka, the mouse.