Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 15)

A native of the Georgia coast, Taylor Brown offers readers his fourth novel, Pride of Eden, as an “environmentalism” tale of majestic animals that should be living in the wild, and the flawed characters who fight to save them from human exploitation.

A native of the Georgia coast, Taylor Brown offers readers his fourth novel, Pride of Eden, as an “environmentalism” tale of majestic animals that should be living in the wild, and the flawed characters who fight to save them from human exploitation.

Brown’s work has appeared in the New York Times, The Rumpus, Garden & Gun, Chautauqua, The North Carolina Literary Review, and many other publications.

He is the author of a short story collection, In the Season of Blood and Gold, and each of his three previous novels, Fallen Land, The River of Kings, and Gods of Howl Mountain, became a finalist for the Southern Book Prize. He has also captured the Montana Prize in Fiction.

An Eagle Scout who graduated from the University of Georgia in 2005, Brown has lived in Buenos Aires, San Francisco, and the mountains of western North Carolina. Today he makes his home in Savannah, Ga.

Pride of Eden reveals environmental and moral lessons through a narrative that combines the heroism of its flawed characters with the tenderness and fury of the animals they work to save–AND “an underworld of smugglers, gamblers, breeders, trophy hunters and others who exploit exotic game.” It’s also an original, out of the ordinary kind of story. Tell me how you formed the idea for this tale–you must be an enormous animal lover yourself!

Taylor Brown

Indeed, I’ve always been an animal lover, and animals have always found their way into my work–though more indirectly until now. A few years ago, I visited Carolina Tiger Rescue in Pittsboro, North Carolina–a big cat sanctuary that takes in tigers, lions, ocelots, servals, and other wild cats from all over the region. There’s a story behind every denizen there, and most come from pretty bad conditions such as roadside zoos, negligent private owners, circuses, etc. Their stories really moved me, and I began to formulate the idea of someone who took the “rescue” part of an exotic wildlife rescue quite literally…

Main character Anse Caulfield is a retired racehorse jockey and Vietnam veteran who runs Little Eden, an exotic animal wildlife reserve off the Georgia coast. He lives to rescue elephants, big cats, rhinos, and other animals, to save them from a life lived in sideshows or as part of a hunter’s “collection.” What drove Anse to devote his life to this cause?

Anse has witnessed, and even been an accessory to, a lot of trauma visited on the animal kingdom, whether it was his experience in Vietnam, his time as a soldier of fortune in Africa, or his career as a quarter horse jockey. So, I think he’s burdened with a lot of guilt and hoping to atone for some of those things in his past, whether they were his own sins or those of his fellow man. That said, he’s a bit of an outlaw and curmudgeon at heart, and he doesn’t always go about things in the most legal manner.

Author Ron Rash has called Pride of Eden a “visionary novel of scarred souls seeking redemption not only for themselves but, in their limited way, for us all.” In what ways would you agree with this observation?

I do think the characters in this book are seeking redemption in their own way. Most of them are dealing with some trauma in their past that continues to haunt and pain them on a daily basis. One of the beautiful things about our species is that we often heal through helping others, be they our fellow humans or members of the animal kingdom.

I think these characters–Anse and Malaya especially–have witnessed things that make them question the “humane-ness” of humanity. By working to help these captive and abused animals, they’re helping to redeem not only themselves, but their faith in humanity as a whole. On the other hand, they’re certainly not saints–they’re as flawed as anyone, and things don’t always go according to plan.

In addition to the obvious flashes of your sizable imagination throughout Pride of Eden, you add a dash of mystery. Is there any chance there will ever be a sequel to this story?

Thank you, Jana. That mystery reminds me of the words of a writer friend of mine, Matthew Neill Null, who once said, “The lives of animals are mysterious, and mystery is the lifeblood of fiction.” Those words continue to resonate with me, whether I’m watching the red-tailed hawk that hunts over our neighborhood or writing about the elephants and rhinos I visited in South Africa. I tried to infuse that mystery into the novel.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have some ideas percolating for a sequel to “Pride of Eden.” Without giving anything away, I’m particularly interested in the story of wolf reintroduction in the American West, as well as the work of Animal Defenders International (ADI), who’ve been instrumental in rescuing animals from circuses in various countries of South America and bringing them to sanctuaries in the U.S. and South Africa.

Why is this a book that you believed needed to be written NOW?

Well, I think the clock is ticking for so many species. Scientists say we’re living through the “Anthropocene Extinction,” in which human activity is correlated with extinction rates hundreds of times higher than normal. It may well be the defining story of our epoch.

We’re living in an age when there are about as many captive tigers in the state of Texas alone as left in the wild in the rest of the world, and in 2018, the last male northern white rhino died living under 24-hour armed guard. I can’t imagine living in a world without such magnificent creatures. I think, if we’re more intimate with the lives and stories of animals, we may be more likely to love, respect, and protect them – and in the process, save something crucial of our own hearts.

Taylor Brown will be at Lemuria on Monday, March 23, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss Pride of Eden.

Sisters of the Undertow is not a long book. It also is not a quick or easy read requiring little thought or mental involvement.

Sisters of the Undertow is not a long book. It also is not a quick or easy read requiring little thought or mental involvement.

A native of the Georgia coast, Taylor Brown offers readers his fourth novel,

A native of the Georgia coast, Taylor Brown offers readers his fourth novel,

Bass Reeves—a real, historical figure—was born a slave on an Arkansas plantation in the 1840s. In Sidney Thompson’s new novel,

Bass Reeves—a real, historical figure—was born a slave on an Arkansas plantation in the 1840s. In Sidney Thompson’s new novel,  An assignment to cover the press premiere of a movie 30 years ago would bring a decades-old Mississippi murder case back into the nation’s spotlight–and change the life of not only court reporter Jerry Mitchell, but untold numbers of many who thought justice would never come.

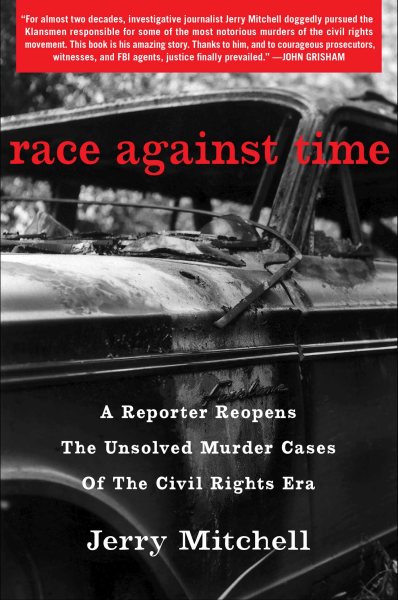

An assignment to cover the press premiere of a movie 30 years ago would bring a decades-old Mississippi murder case back into the nation’s spotlight–and change the life of not only court reporter Jerry Mitchell, but untold numbers of many who thought justice would never come.

In

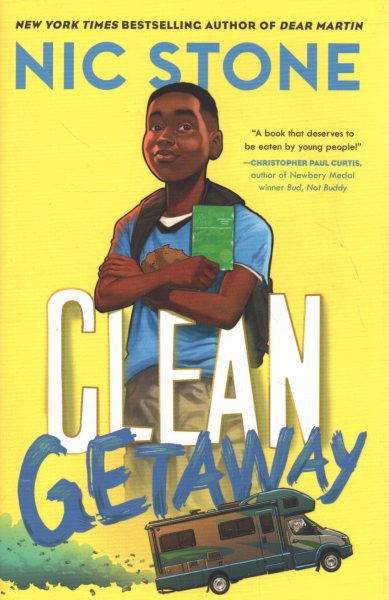

In  When his grandmother, his beloved “G’ma,” shows up in an RV at the beginning of his spring break, to jailbreak him from being grounded, he jumps at the chance. He writes a note to his dad, and leaves his phone at home so he can’t be called. Just the wide open road, and the person he adores and trusts most in the world.

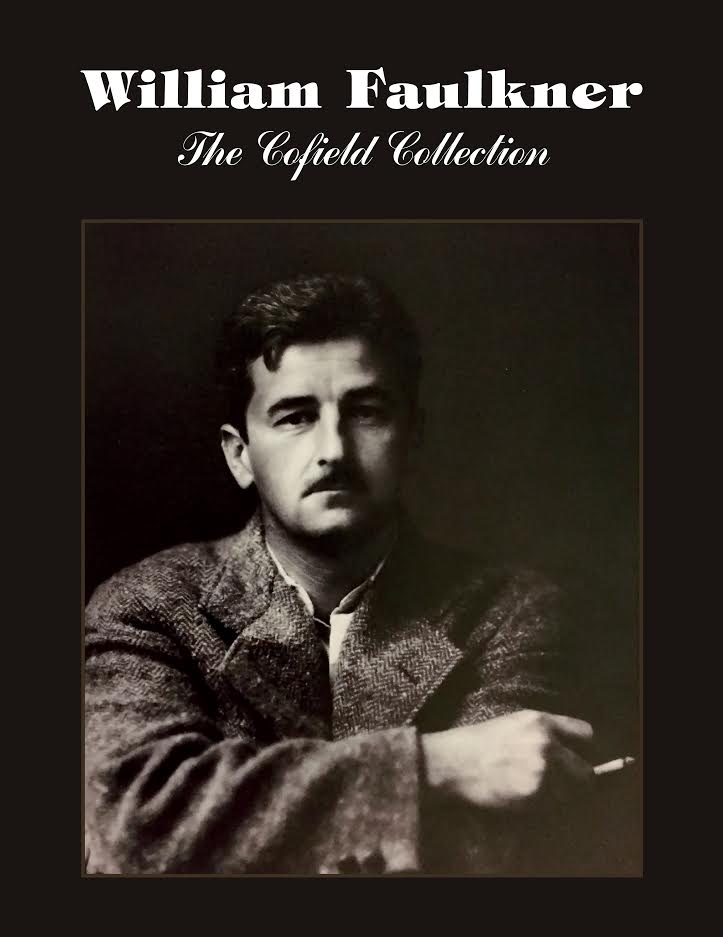

When his grandmother, his beloved “G’ma,” shows up in an RV at the beginning of his spring break, to jailbreak him from being grounded, he jumps at the chance. He writes a note to his dad, and leaves his phone at home so he can’t be called. Just the wide open road, and the person he adores and trusts most in the world. “It wasn’t easy to get a smiling photograph of William Faulkner!” That was the fond, exasperated comment of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield, the Oxford photographer in whose studio Faulkner sat for the portraits that graced the dust jackets of his novels.

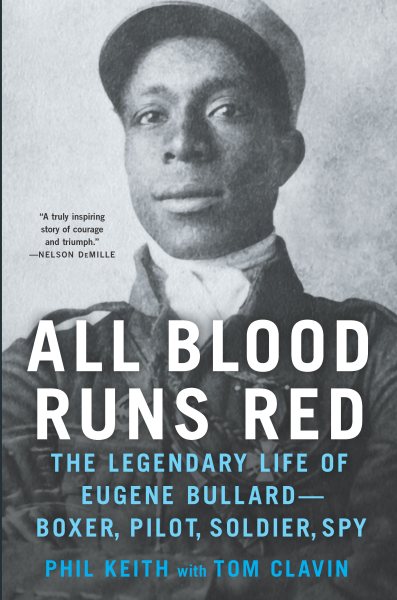

“It wasn’t easy to get a smiling photograph of William Faulkner!” That was the fond, exasperated comment of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield, the Oxford photographer in whose studio Faulkner sat for the portraits that graced the dust jackets of his novels. Author Phil Keith adds his sixth book to his collection as his collaboration with bestselling writer Tom Clavin unfolds the almost unbelievable story of bravery and valor of a little-known World War I hero in

Author Phil Keith adds his sixth book to his collection as his collaboration with bestselling writer Tom Clavin unfolds the almost unbelievable story of bravery and valor of a little-known World War I hero in

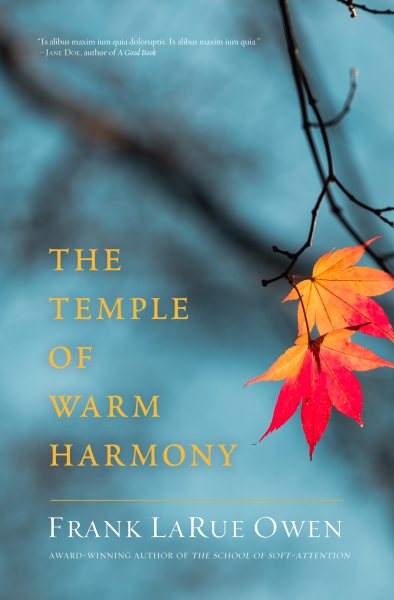

“Afoot and light hearted, I take to the open road.” So begins Whitman’s long poem “Song of the Open Road,” a delightful, meandering meditation on what it means to be human. A theme that Whitman hammers into this poem, without a hint of subtlety, is the familiar “the journey is the destination,” a trope that has had countless iterations over time. Frank LaRue Owen’s new book,

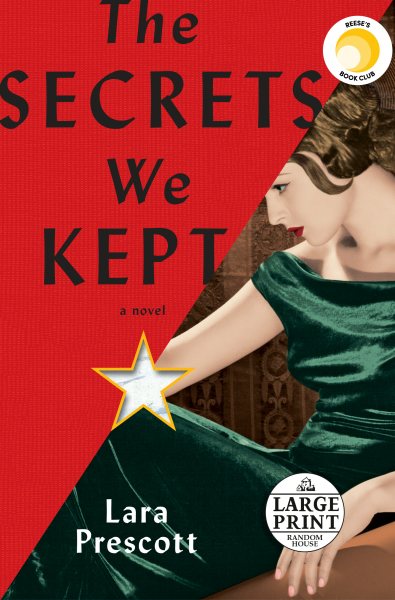

“Afoot and light hearted, I take to the open road.” So begins Whitman’s long poem “Song of the Open Road,” a delightful, meandering meditation on what it means to be human. A theme that Whitman hammers into this poem, without a hint of subtlety, is the familiar “the journey is the destination,” a trope that has had countless iterations over time. Frank LaRue Owen’s new book,  Lara Prescott’s fictional account of three young women employed in the CIA’s typing pool who rise to the upper echelons of espionage during the 1950s Cold War is based on the true story of the agency’s undercover plan to smuggle copies of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago into the USSR.

Lara Prescott’s fictional account of three young women employed in the CIA’s typing pool who rise to the upper echelons of espionage during the 1950s Cold War is based on the true story of the agency’s undercover plan to smuggle copies of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago into the USSR.